Portfolio

Studio of the Mind

On the work of Zeng Fanzhi and the art that surrounds him

Zeng Fanzhi’s studio with works on paper in progress, January 2024

- 12 April 2024

- Issue 10

- Artwork © Zeng Fanzhi. Collection of Zeng Fanzhi courtesy the artist. Photography by JJYPhoto

- Related Artist

- Zeng Fanzhi

Giorgio Vasari collected thousands of drawings by fellow artists and predecessors dating back to the 14th century. Degas’s personal collection filled his Paris apartment, the pace of his purchases so fierce it worried friends. Howard Hodgkin collected Indian court paintings. Warhol collected cookie jars, Native American art and Art Deco drawings (among many, many other things). Hanne Darboven collected raucous kitsch knickknacks. Hiroshi Sugimoto collects—along with artworks—fossils, religious artifacts, antique torture devices and meteorites. “My collection is my mentor,” Sugimoto told The Financial Times in 2015, on the occasion of a show of artists’ wildly multifarious personal collections at the Barbican in London, “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector.”

But the calculus by which artists’ personal collections serve as mentor has never been straightforward, and the lines of influence are often as mysterious to the artist as to anyone else. “On the whole, there are few specific correspondences between the subjects of the works Degas collected and those of his own art,” the curator Ann Dumas wrote in an essay for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition “The Private Collection of Edgar Degas” in 1997 and 1998.

Three recent paintings by Zeng, from left: Arhat VII, Arhat VI and Arhat IX , 2019–2023, oil on canvas

Zeng Fanzhi and Gladys Chung, director of the Fanzhi Foundation for Art and Education, in front of Untitled (2019–2023) and drawings in progress

Three mixed-media works on handmade paper by Zeng. Sculpture: Ernst Barlach (1870–1938), The Singing Man, conceived in 1928 and cast before 1939

For decades, the artist Zeng Fanzhi has been building a highly idiosyncratic synthesis of artmaking and personal collecting in his studio in Beijing, a minimalist two-story structure in the city’s northeastern Caochangdi neighborhood. Zeng, born in Wuhan, Hubei Province, in 1964, has long been interested in the complex artistic intersections of Eastern and Western painting traditions. “The influence of Eastern art on me is mainly in aesthetics and taste,” he recently told Ursula. “And the influence of Western art is more related to the training of painting skills. I revisit, from time to time, Western painting traditions. And I always have new discoveries and inspirations, which are reflected in my painting practice at each stage.”

From the late 1980s to the present, Zeng has categorized his work as belonging to four major phases. He first gained international recognition for his Hospital series (1991–94), dominated by figuration; his subsequent Mask series (1994–2004) investigates how the inner self can be revealed through visual concealment. After 2002, he began moving markedly into abstraction and said of this shift: “The influence of classical Chinese art on my aesthetics, as well as on my painting practice, is reflected in the development of my abstract work.”

Drawings by Adolph von Menzel (1815–1905) near Zeng’s study

Adoph von Menzel, Seated Woman, 1891. Graphite with stumping and black chalk

Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009), Pageboy, 1979, pencil on paper

Statue, Tang dynasty, ca. 618–907

Built and designed as a place for study and contemplation as well as for making work—as much gallery and library as studio—Zeng’s base of operations in Beijing is an embodiment of his adventurous cross-cultural approach, its collection containing an unorthodox and at times surprising combination of work. In his study hangs a work by the avant-garde Japanese calligrapher Yu-ichi Inoue. The table below is adorned with intimately sized works by Mark Tobey and Käthe Kollwitz. Drawings by Adolph von Menzel and Andrew Wyeth are nearby on one of the living area walls.

The work of Menzel, in particular, has been a touchstone for him. “When I was fourteen or fifteen,” he says, “my uncle bought me a catalogue of Menzel’s famous sketches of the workers in an iron-rolling mill. It was very memorable to me. I hadn’t seen the originals until 2010, when I traveled to Berlin. When I was learning painting, I drew a lot of studies after Menzel. His works demonstrate a gripping play of light and shadow, with rich details, in contrast to the concise way, for example, drawings by Schiele function.”

On wall: Yu-ichi Inoue, Torai, 1963, ink on Japanese paper. On table: Drawings by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) and Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945); a tempera painting by Mark Tobey (1890–1976); and other objects of art

Of Zeng’s own work and the works by others he brings into his collection, he says: “There are no direct relationships. They are just part of my visual experiences, among others. And it’s not only artworks. I love observing beautiful things in this world. Throughout the studio, I display stones I’ve collected from various places. There are even old stone slabs inlaid on the ground of my study. They once served as national roads in ancient times. After being rolled over by wheels and naturally weathered, they’ve formed a unique color, luster and texture. I spend a long time observing these stones and their subtle changes in form under the moving natural light. These mixed aesthetic experiences are gradually internalized and then influence my creation.”

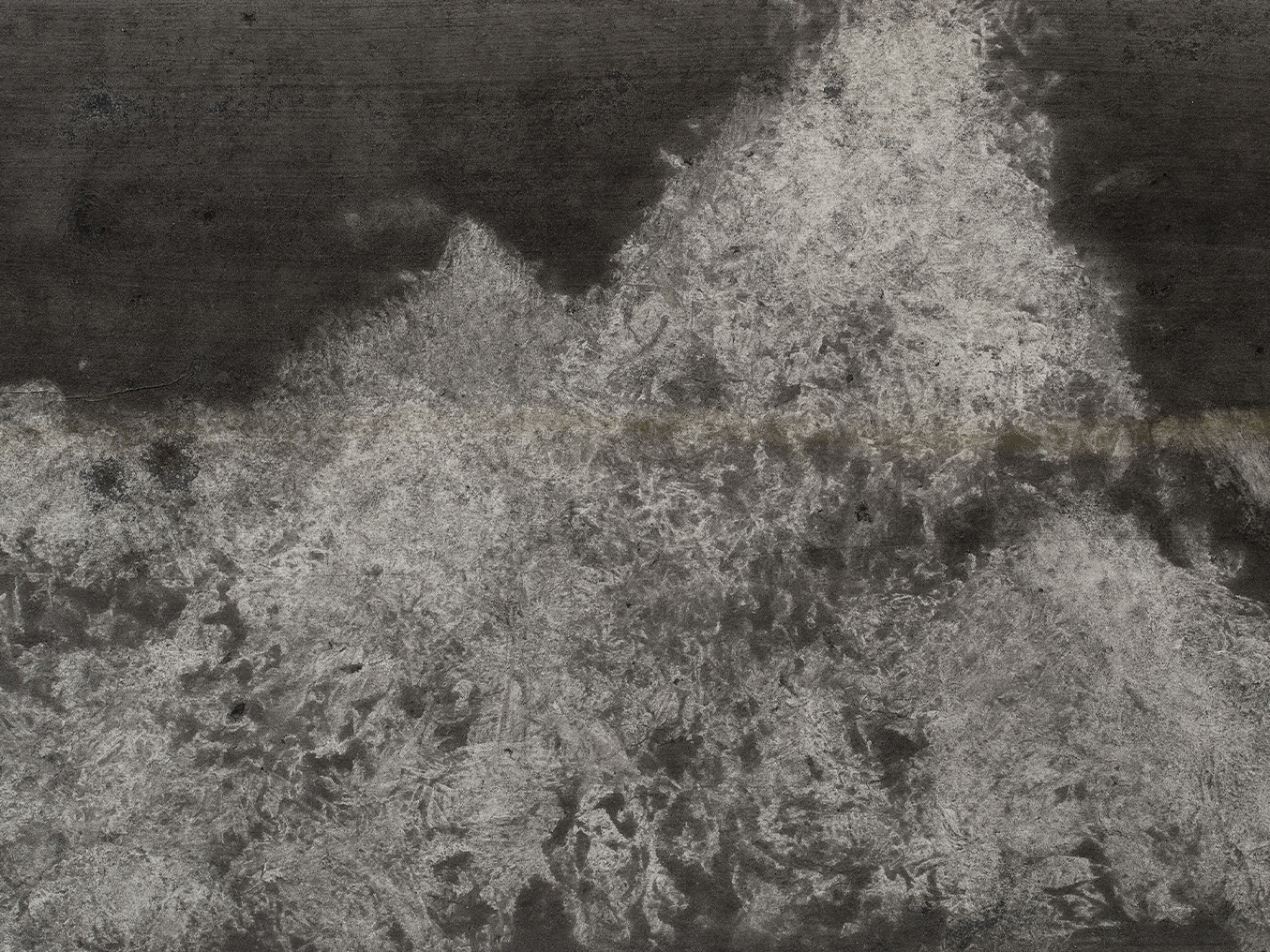

Mixed-media work on handmade paper from 2017 (detail)

Mixed-media work on handmade paper from 2015 (detail)

Arhat VI, 2019–2023, oil on canvas (detail)

Arhat VII, 2019–2023, oil on canvas (detail)

–

“Zeng Fanzhi: Near and Far / Now and Then,” an exhibition organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, opens April 17 and continues through September 30 at the Scuola Grande della Misericordia in Venice, Italy.