Essays

On the Rim of the Wheel

The lost history of the Lower Manhattan artists’ building 76 Jefferson Street

By Erik La Prade

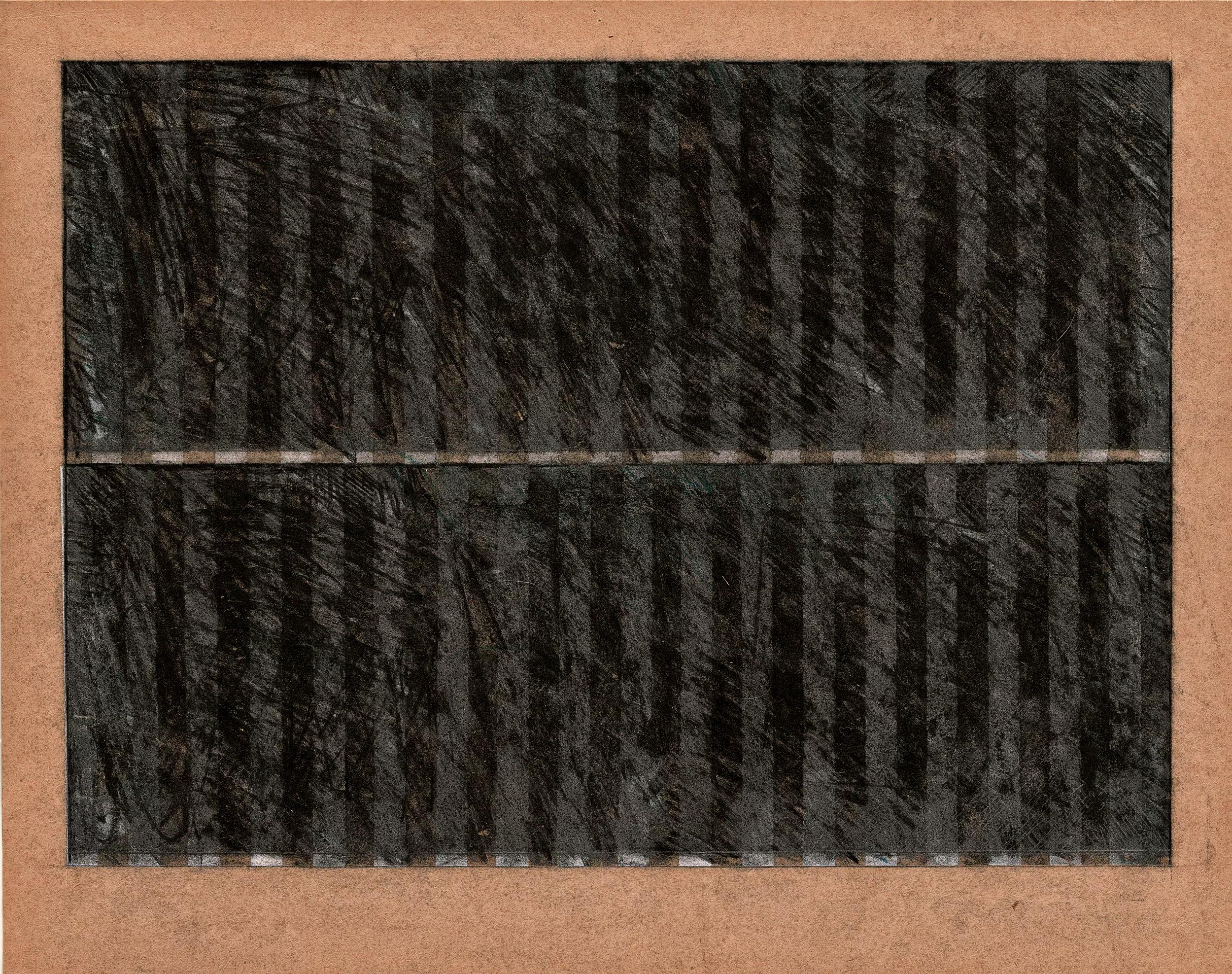

Richard Kalina, Untitled, 1968. Installed on the interior of Jefferson Street. Courtesy the artist

During the decades after the end of the Second World War, from the 1950s through the 1970s, a majority of industrial businesses based in Lower Manhattan, such as rag merchants, tool and die makers, fabricators and wholesalers of manufactured goods, vacated their buildings and relocated to more spacious areas outside New York City as the demographics of their businesses changed. The industrial lofts they left behind became magnets for artists eager to find cheap, roomy spaces in which to live and work.

In an article in The New York Times Magazine in 1962, Gilbert Millstein wrote: “Exactly how many painters and sculptors are to be found in these lofts nobody really knows, not even the authorities, but a competent consensus in the art world is that, of the 30,000 or so artists in the metropolitan area, between 5,000 and 7,000 inhabit or labor in lofts.” It’s likely that the number of artists Millstein quotes could have been higher since many artists living illegally in lofts were undocumented and sublet spaces to friends in order to help cover the rent.

The story of the New York artist loft revolution has long centered around SoHo and for many reasons rightly so. Political demonstrations and protests that occurred in SoHo beginning in the early 1960s, to save the neighborhood from demolition and redevelopment, brought into sharp focus many of the problems artists faced in New York in those years: summonses for illegal habitation; unannounced evictions; lack of heat; tickets for building violations. The publicity surrounding these issues reverberated powerfully with artists, art school students and even non-artists looking to score large, cheap lofts. As a result, SoHo became synonymous in the popular imagination with the artist loft movement, along with a concurrent narrative that artists were soon priced out of the area and began looking elsewhere.

But that “elsewhere” had already been humming with artist activity well before SoHo became the center of the downtown art scene. The painter Richard Kalina remembers: “It wasn’t as if SoHo came into existence and all the other places were peripheral. Artists lived in SoHo, but SoHo coalesced from neighborhoods around it. What seemed to be peripheral when SoHo was the center was where the artists already were: in Chinatown; on the Bowery; in the West Village; in the old Ninth Street area around Cooper Square; many already in Chelsea. The rim of the wheel was actually where the art was and then it sort of got filled in, in places like TriBeCa and SoHo.”

Kenneth Kilstrom exiting 76 Jefferson Street, ca. 1975. Courtesy Robert Lobe

Three important artists’ areas on the rim of this wheel were located in Lower Manhattan and each had its own special profile. Perhaps the most well-known today was Coenties Slip, a single street near the South Ferry and the Fulton Fish Market. Between 1954 and 1960, Fred Mitchell, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist and others lived and worked in the abandoned lofts found on the Slip; Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg had lofts nearby on Pearl Street. A second major artist area coalesced along the Bowery, from Chatham Square at Park Row to Cooper Square and East Fourth Street, whose cheap spaces European refugee artists like Fernand Leger had discovered by the early 1940s, to be joined over the next few decades by Mark Rothko, John Giorno, Eva Hesse, Elizabeth Murray, Al Loving, Tom Doyle, Robert Lobe, Michael Steiner, Mary Heilmann and many others.

The third area of intense activity in Lower Manhattan—by far the least known and documented of the three, though it nurtured the early work of several important artists—centered around a single block of Jefferson Street. The street was one of dozens surrounding the South Street Seaport that had once been hives of industry for commercial shipping and supply businesses servicing the New York Harbor and East River waterfront. (Jefferson Street was originally known as Washington Street, named for George Washington, but it was later renamed for the third president of the United States.) In the early part of the 20th century, Jefferson Street extended from East Broadway to Water Street. It was bordered by Rutgers Street on the south side and Clinton Street on the north, crossing Henry, Madison, Monroe and Cherry Streets before ending at Water Street. Today, the street extends only from East Broadway to Madison Street, truncated by the massive Mitchell Lama housing redevelopment of the Seaport area that radically transformed the neighborhood between 1955 and the mid-1970s and resulted in the razing of most of its oldest structures.

The building that Kalina, Jenney and a host of other artists moved into was essentially a 19th-century anomaly that had somehow survived to perform a final function: as an incubator of late 20th-century art, a tumbledown site for young artists’ beginnings.

The building at 76 Jefferson Street, constructed in 1893, was among the last to be torn down, in 1977. Its eighty-two-year history represents a microcosm of the changing fortunes of the neighborhood itself. Originally a loft where sails were produced for ships, it later housed a saddle-making factory; an (alleged) bordello; and, by the 1930s, a horse stable for delivery wagons and carts used by immigrant rag merchants. The artist Neil Jenney, who moved into the fourth floor in the summer of 1967, remembers that the rear of the building served as a parking lot for New York Post delivery trucks. Kalina, who also took up residence in 1967, on the fifth floor, remembers the building as being metaphorically, and also literally, porous.

“You could look through the cracks and see the East River,” he says. “It was still part of the old American commerce industry. Shipping was still there and being near the water, it had a particular smell, partly from the spice factory on Water Street. At the end of the street, there was a very active pier for smaller cargo ships. You could stay up all night or get up early and walk to the Fulton Fish Market, to eat at Sloppy Louie’s.”

The building that Kalina, Jenney and a host of other artists moved into was essentially a 19th-century anomaly that had somehow survived to perform a final function: as an incubator of late 20th-century art, a tumbledown site for young artists’ beginnings, providing them with freedom to work, to find their place within the burgeoning New York art world and to spark off fellow artists.

The first wave of artistic communities to inhabit 76 Jefferson seems to have arrived in 1959, when the painter Anton James leased the building and began subletting lofts (40 x 100 feet each) at low rents to fellow artists, “helping painters, musicians, sculptors and actors to find a dream,” as the writer Madeleine B. Karter described the building at the time in Pageant magazine. James lived and worked in the building, renting to friends and acquaintances such as the sculptor Lothar Wuerslin, the painter Eleanore Mikus, actor Jane Churchman, printmaker and sculptor Yasuhide Kobashi and musician Sammy Joseph, who was known to conduct 2 a.m. jam sessions in his loft. It’s unclear exactly how long James acted as the building’s rental agent, but his ambitions appear to have been short-lived, because by 1961, Jack Klein, who became known as “the loft king,” was living at 76 Jefferson and subletting to artists. Klein had begun his professional life as a salesman in the Garment District, then moved downtown to work as a stock broker trainee before shifting into real estate. He negotiated leases between building owners and artist tenants, becoming a major figure in the downtown market from the 1960s to the 1980s.

The artists Brice Marden and Joe Overstreet were among the first of Klein’s tenants, and Overstreet worked as the building’s super-intendent. Corrine Jennings, Overstreet’s wife, told me that he sublet a loft around 1962 to the jazz musician Eric Dolphy, who would lay out each of his instruments on his bed and spend long periods of time practicing the same notes on each, exhibiting a level of discipline that left a strong impression on Overstreet. In 1966, the sculptor Mel Edwards, part of a second wave of 76 Jefferson artists, moved in for about six months, occupying Dolphy’s former loft. “I stayed with David Novros, and I rented a place down in the South Street Seaport area, 76 Jefferson Street, which had artists in the building: Brice Marden, Janet Fish, Steve Poleskie,” Edwards told the critic Michael Brenson for Bomb magazine.

Exterior view of Jefferson Street, 1968. Courtesy Richard Kalina

“My loft was hardscrabble. I had the floor below Brice Marden, who had a stove, so we’d sit up with our feet on the stove door to keep our boots warm and eat crackers with peanut butter.”— Bob Neuwirth

In a 1972 oral history for the Archives of American Art, Marden recalled his introduction to the building and the sense of belonging it gave him. “I was in New York and I was really anxious to meet people and stuff like that,” he said. “But it was still very difficult . . . There were always Tuesday night openings, and I’d be the only person who would look at anything. Everybody else knew everybody, and I didn’t know anybody. But then you start meeting people, and I met a lot of people through Steve Poleskie, and we were both painting along. That whole building was full of artists . . . lots of really good people.”

Other young artists, including Emilio Cruz and Neil Williams, lived in the building during the mid-1960s, as did an older artist, Kenneth Kilstrom, who had moved to New York in 1945 and become a member of master printer William Stanley Hayter’s Atelier 17 studio in 1947. (Robert Lobe, a later resident of the building, remembers Kilstrom as having, among other interesting traits, a strong interest in flying saucers.) The painter and musician Bob Neuwirth, after traveling Europe as a member of Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Look Back” tour, returned to New York, and Marden, a friend, introduced him to Klein. Neuwirth moved into 76 Jefferson in 1965, taking the loft that had been occupied by Dolphy and Edwards.

“I hadn’t had an art studio for almost ten years when I got it,” Neuwirth told me. “It was a special place for me then. My loft was hardscrabble. I had the floor below Brice Marden, who had a stove, so we’d sit up with our feet on the stove door to keep our boots warm and eat crackers with peanut butter. I didn’t have any idea where I was going to get the next jar of peanut butter, but it was fun.”

The building also played a role in the rise of Pop Art, as one of the homes of Poleskie’s short-lived but highly influential Chiron Press, which was the first print shop in the United States devoted to producing silk-screen prints; among its artists were Warhol, Rosenquist, Oldenburg and Lichtenstein, who made his first screen print, Brushstroke, with Poleskie, in 1965. The press ended its run at Jefferson Street in 1967, as Poleskie sought more time to focus on his own work and the challenges of a post-industrial New York art life piled up around him. “I was becoming tired of my screen-printing shop and all that it involved,” he later wrote. “Fickle artists, paying bribes to everyone—the building and fire inspectors, the garbage man and the police—and of art galleries that didn’t pay their bills.”

His departure from Jefferson marked the beginning of a third and final wave of artists in the building, hastened in part by Klein’s periodic raising of rents. A group of seven young artists—Robert Lobe, Richard Kalina, Valerie Jaudon, Neil Jenney, Gary Stephan, Ed Shostak, and John Duff—all moved in between 1967 and 1969. Lobe remembers meeting Janet Fish as she was moving out and he was moving in. Demand for the kind of raw, roomy space the building offered seemed to hold steady even in the face of higher rents. Stephan, who had graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute and was living in the East Village in the mid-1960s, told me that when he learned of a loft coming open at Jefferson, he traveled downtown for an appointed showing and arrived to find eight other artists already waiting for the superintendent, Tony Murad. “The door opens and we all walk in and I said, ‘I’ll take it!’ Some of the other people complained, ‘Wait a minute! We didn’t even look at it.’ But Tony said: ‘It’s over,’ and that settled it. Except for one person who challenged me for the loft by flipping a coin for it. So I said okay and we flipped and I won the toss and the loft. It was on the fourth floor, north side of the building. It was a thousand square feet and I paid seventy-five dollars a month rent.”

Portrait of Janet Fish, ca. 1970. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York. © Janet Fish

Emilio Cruz, 1969. Courtesy Corbett vs. Dempsey

Stephan in turn told a friend, the sculptor John Duff, about the building, and Duff was able to rent on the first floor in 1968, inheriting the Dolphy-Edwards-Neuwirth loft. Neuwirth had moved to a new space in the building, and when he left in 1968, Ed Shostak replaced him. Prior to moving to New York, Duff had visited Bruce Nauman’s studio in Davis, California, and remained friendly with Nauman. When Nauman had an early exhibition at the Castelli gallery in New York in 1968, Duff went and afterward attended a party for Nauman given by the curator and collector David Whitney at his Canal Street loft, where, as Duff told me, he got drunk. At some point during the evening, he found himself being embraced and kissed by someone he didn’t know: Jasper Johns. As the party wound down, Johns, Duff and Whitney ventured out for breakfast, and a week or two later, Duff visited Johns’s Bowery studio, reintroducing himself. It was the start of a long friendship and a relationship in which Johns became one of Duff’s most devoted patrons, buying works from many shows over the years. (In the late 1960s, Johns needed an assistant and offered Duff the job; Duff turned it down and Gary Stephan took the job instead.)

Artists often found work with each other, spanning generations. Brice Marden had briefly worked as Poleskie’s assistant before moving to work in Robert Rauschenberg’s studio. When Marden left Jefferson in 1967, Kalina moved in, and when Poleskie vacated his loft the summer of the same year it was taken by Lobe, who recalls giving Poleskie two hundred fifty dollars key money. Kalina met Jaudon at a Larry Poons show at the Lawrence Rubin Gallery on West 57th Street in October 1969, and soon after, she moved into Kalina’s Jefferson Street loft.

Jaudon told me: “The place was such a dump. It was so dangerous. I thought it was all fabulous. The stairway was just barely walkable. There was a sign on the wall next to the stairs, dated from 1945 which said, ‘Women and children are not allowed on the stairs.’ And I thought that was so cool.”

Neil Jenney moved to New York in December 1966 and found a three-room apartment on East Sixth Street between Avenues C and D, “a dicey neighborhood on the Lower East Side, known for drug dealing and gangs,” he recalls.

In those years, the German art dealer Kasper König owned lofts in Chinatown, and Jenney told him he was looking for art studio space. “He told me Brice Marden had just moved out of his loft,” Jenney says. “Kasper gave me Marden’s phone number, but it worked out it was actually Rauschenberg’s number, since Brice was working for him. I called Marden but he had already given the loft to Richard Kalina. I decided to go down to 76 Jefferson Street anyway. When I got to the building, I looked it over—there was no buzzer for the front door and no names on the door either! So I stepped back into the street and looked up and just at that moment Bob Lobe stuck his head out of a window. I yelled up, ‘I’m looking for a space! Are there any spaces in this building?’ Lobe said, ‘I don’t know.’ But he came down and let me into the building, and that was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Neil Jenney and Robert Lobe standing on Lobe’s Early Walk On, 1967-68. Photo: Robert Lobe. Courtesy the artist

Jenney immediately fell for the building and the area around it. He moved into the fourth floor, paying eighty dollars a month. He remembers Jefferson Street as a distinctive kind of artist community, though not exactly an experimental alternative space like 112 Greene Street in SoHo, which presented public exhibitions and long-term artist projects. Artists at 76 were venturing ambitiously into new media and forms and approaches to sculpture and painting, but the building was not public-facing, and feedback and criticism tended to come from artists within the building’s circle. While the residents of Jefferson Street were highly social, the building was not a social scene itself, the way some loft buildings in SoHo and Chinatown were. In part, this had to do with the precarious condition of the building. Lobe remembers that the gas meters in the basement had been ripped off the wall and were lying in the mud. Because of this, earlier tenants had connected makeshift rubber hoses from the main gas line on the street to their individual lofts. Tenants were warned at all costs never to let Con Edison or fire inspectors into the basement of the building or even into the building itself. Neuwirth remembers that the basement was practically inaccessible anyway, “generally covered with water and if the basement really flooded, the rats would just move up to the first floor.”

Lobe remembers “socializing” at Jefferson Street as involving the purchase of a two-dollar six-pack of Schaefer beer and a twenty-five-cent slice of pizza from a nearby corner store. Stephan told me of saving spare change, trying to accumulate at least thirty-five cents, enough to buy an imported beer on an evening when he did go out. A working-class neighborhood bar stood on the corner, patronized more by local cops than by artists. Aside from uptown gallery openings or loft parties, the Jefferson Street artists tended to socialize at Max’s Kansas City, the club founded in 1965 by Mickey Ruskin on Park Avenue South.

To a degree, many told me, they thought of themselves as part of an older sensibility more akin to that of the Abstract Expressionists: artists who elected to be, in some sense, outsiders, working and living outside the prevailing system. The system, though, as it does, eventually discovered them, and the art they made found its way slowly into the mainstream, in some cases signaling a shift in the style of art being shown in New York and in the way people viewed it. Marden developed his early Minimal works, shown in his first exhibition at the Bykert Gallery, in 1966, while living and working at Jefferson Street. Jenney developed his early painting style that came to be known as “Bad Painting” there, and Jaudon painted her first patterned works, becoming one of the artists who originated the innovative movement known as Pattern and Decoration. At Jefferson, Kalina created his shaped canvases using polyester on canvas; Stephan created his early series of geometric forms by baking polyurethane in an oven; Duff made sculptures using found objects or by fashioning clay into abstract shapes; and Neuwirth painted his geometric, hard-edged canvases.

Brice Marden, Untitled, 1964-65. Charcoal, pencil and colored pencil over screen print on brown paper, 16 x 20 in. (40.8 x 51 cm). © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. © 2023.Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Joe Overstreet, The New Jemima, 1964/70. Acrylic on canvas over plywood construction, 102 3/8 x 60 3/4 x 17 1/4 in. (260 x 154.3 x 43.8 cm). The Menil Collection. Photo: Paul Hester. © Joe Overstreet/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Many [Jefferson Street artists] thought of themselves as part of an older sensibility more akin to that of the Abstract Expressionists: artists who elected to be, in some sense, outsiders, working and living outside the prevailing system.

In 1976, the curator Richard Marshall organized an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that showcased thirty-eight works made by eighteen of the artists who had lived at Jefferson Street over the years, along with prints created by Poleskie’s Chiron Press. The timing of the show was ironic and bittersweet. As it opened, the building, which had been officially condemned by the city in 1972, had already been slated for demolition to make way for the Two Bridges urban renewal project.

Klein no longer managed the building or collected rents from its tenants, but a number of artists continued to live there, some paying nothing. According to Scott Davis, who lived in a sublet at 76 Jefferson from 1974 to 1976, the city had to raise money for the building’s very demolition, a process that would take five years. In 1972, Jenney moved to SoHo but continued to maintain his Jefferson Street loft for studio and storage space. Stephan moved out in 1976, around the same time as Lobe. Kalina and Jaudon moved to the Bowery in 1977. Shostak may have been the last resident to move out, shortly before the building ceased to exist.

As isolated and precarious as it was, the building is mourned to this day by many of its residents, who hope that more of its history finds a rightful place in the record of the groundbreaking New York art world of the 1960s and 1970s.

“We were living in a sordid neighborhood with our heads in the clouds,” Jaudon says. “But we were like good neighbors.”

–

Erik La Prade is a writer and photojournalist with a special interest in the arts. His writings and artist interviews and have appeared in Art in America, BOMB, The Brooklyn Rail, ArtCritical and other publications. His is the author of Breaking Through: Richard Bellamy and the Green Gallery, 1960–1965: Twenty-Three Interviews (2010). La Prade’s fifth collection of poetry, Ancient Light, will be published by Last Word Press this year.