Books

Dieter Roth: Collected Interviews

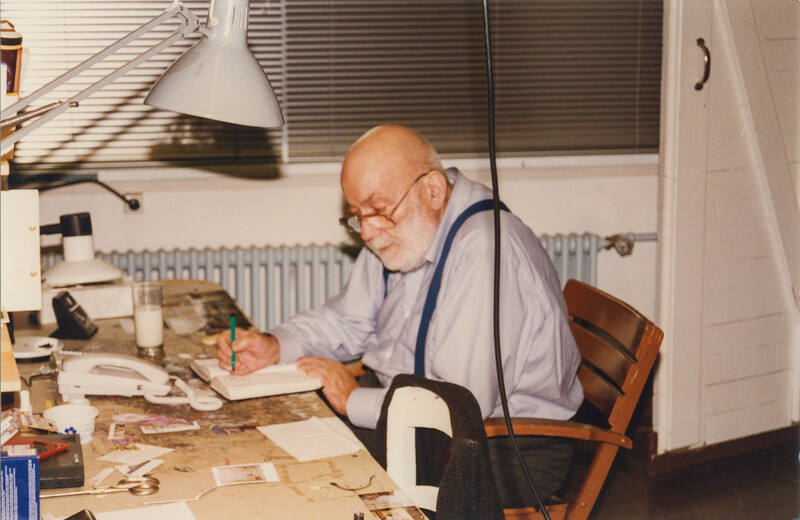

Dieter Roth during an interview with Peter P. Schneider and Simon Maurer at Hauser & Wirth Zürich, 1998 © Dieter Roth Estate. Photo: Thomas Burla

The oeuvre of Dieter Roth (1930 – 1998) encompasses painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, film, video, music, typography, design, architecture and, last but not least, literature. ‘His books alone would give him a place of honor in twentieth-century art’, wrote artist Richard Hamilton, who championed Roth very early on. In his interviews, Roth offered many surprising and fascinating clues to his life and thought. The majority of the interviews were in German and Swiss German, and for the first time are available unabridged in English in a new publication edited by Barbara Wien.

Included are the Hamilton interviews, and the very intimate interview Roth conducted with Patrick Frey just a few days before his death. Read below an excerpt from the essential conversations with Irmelin Lebeer-Hossmann in 1979.

So you don’t have a particularly traumatic relationship with time?

I don’t think so, no. I enjoy it when I get the feeling that time is running out and then I can really speed things up, get things done really fast. There are times when I’ve promised to do something and I’ve procrastinated and then suddenly find that there’s ‘no time left’, as the saying goes—and that I can just cut right through that problem by coming up with an idea, which, so far (knocks on wood) has almost always worked for me. So time isn’t a problem for me. I always think that one idea can make up for years of lost time. That’s kind of true, isn’t it?

What do you mean by ‘idea’—what is an idea for you?

Well, it’s when I can suddenly do something without thinking. When I know that someone inside me has been mulling that over for a few years. That’s how I see it. When I can simply do something and everybody says: hey! Now that’s an idea!

Give me an example—

Well, for instance, one idea that I’ve pushed a bit is the one with the slot books. The ones you keep turning. I don’t know whether you’re familiar with them. Everybody always goes ‘ah!’ Or at least they did back in the day, twenty or so years ago. Or the mould pictures. Or now the thing with the ‘Flat Waste’. I wait—I wait until the ideas are fully formed. Sometimes an idea will come to me and I won’t act on it for another ten years. I’ve learned not to push it. Before, when I was doing advertising graphics, you had to push the ideas if you were an employee. And I always found it really troubling that something you had in mind had to be put to hand. Because it’s something vague and, in a way, it has a life of its own. And once I was independent—I set myself free and didn’t take on any more employment contracts—I noticed that I couldn’t force myself to develop anything—maybe due to lethargy or laziness or whatever. I always have to wait until I’ve got it and then I look at myself—before, I often used to look at myself sadly when I had an idea that I was always carrying around with me that would surface now and again, but I couldn’t push it, and couldn’t formulate it clearly. And sometimes that idea will surface again in ten or fifteen years, and it has a form then.

And then there are also situations—such as writing poetry—in which you avoid thinking and just plunge into the mist? When the idea emerges out of the work, rather than vice versa?

Yes, that may be the case. Sometimes, when you think you’ve got an idea, in a group of drawings for instance, you realise, I didn’t have that idea at all. The idea simply ran past me. I just drew that without knowing what I was doing.

How long have you been doing that? That takes great mastery.

What does ‘great mastery’ mean?

You have to be able to draw perfectly, and overcome the barriers between mind and hand.

You can turn the mind off. You don’t have to think about what you’re doing, or make comparisons. It’s best to have a hangover or a really melancholy depressive state—they’re good for that. Then you can draw mindlessly for hours. For days, without even looking, as it were.

Without even imagining an object?

Yes, just like that; wishy-washy.

And do they turn out to be abstract drawings or figurative ones?

Well, they always turn into something. For years, they’ve always turned into something. Always some monsters or living creatures or suchlike. I put them together in books. Unfortunately, I don’t have those here. I’ve done hundreds of drawings, which I always put together in small groups. For instance, one group is called ‘Cheeky Monsters from the… Street’. You know, on one of those days when I’m hungover, I’ll sit down in the morning and draw because I can’t sleep any more. And they just tumble out. And I don’t just do one, but a whole stack of them. And when I can’t go on with a drawing and it just sickens me, I shove it underneath the pile and start on the next one. That goes on all day and then they’re finished. Well, these ones here took two days. (A stack of drawings lying on the table)

Then the drawings I’m doing disgust me, or the TV disgusts me, and then I’m disgusted at myself, and that creates a strange… I don’t know for sure, but next morning I wake up feeling reborn. And looking at the drawings later, they’re quite beautiful.

And you drew them completely unconsciously?

Yes, they actually repulse me. I can’t bear to look at them too closely. I just descend into a melancholy mood, into my depression.

And does that provide relief?

No. The relief is, quite simply, I think, because the body regenerates by sitting quietly, resting. I can’t sleep then, because when I’m lying down I can’t switch off.

So it’s a form of relaxation for you—

Yes. Sometimes I’ll do that for three days, and then there’ll be a heap of drawings. Afterwards I don’t remember at all what I’ve drawn. And sometimes I switch on the TV so that I don’t have to look at the drawings, but just watch some crap or other and that often makes me feel even worse. And then there are moments of calm, when the sense of revulsion is enormous. That’s when I don’t dare to think of anything to do with myself. That can be liberating in a way. Then I just get on with it. Then the drawings I’m doing disgust me, or the TV disgusts me, and then I’m disgusted at myself, and that creates a strange… I don’t know for sure, but next morning I wake up feeling reborn. And looking at the drawings later, they’re quite beautiful. They’re not repulsive at all. But, believe me, when I’m drawing them, I find them repulsive.

And they’re simply always monsters?

Yes. That’s why I always call them ‘self-portraits’. Because that’s how they’re done. Most of the self-portrait drawings. With a hangover.

In your mind, is there a difference between drawing a monster and a self-portrait?

They’re the same. They’re all self-portraits, really.

Including these drawings here?

Yes, of course.

How can they be identified as self-portraits?

Because they have a circle in which all of this happens. I always have the feeling that there’s this circle here, and inside it there’s this roiling mess. I very rarely have the feeling of reaching out; everything is always contained, like this, simmering away.

These here are two figures, aren’t they?

Yes, yes. They’re splitting now. But two or three months ago, they weren’t split. There’s a lower figure and an upper figure, you see.

Is that a good development or a bad one?

I note with astonishment that that’s just the way it is. Because I try not to think things through when I’m drawing. So I can just let things come to me—that happens all by itself.

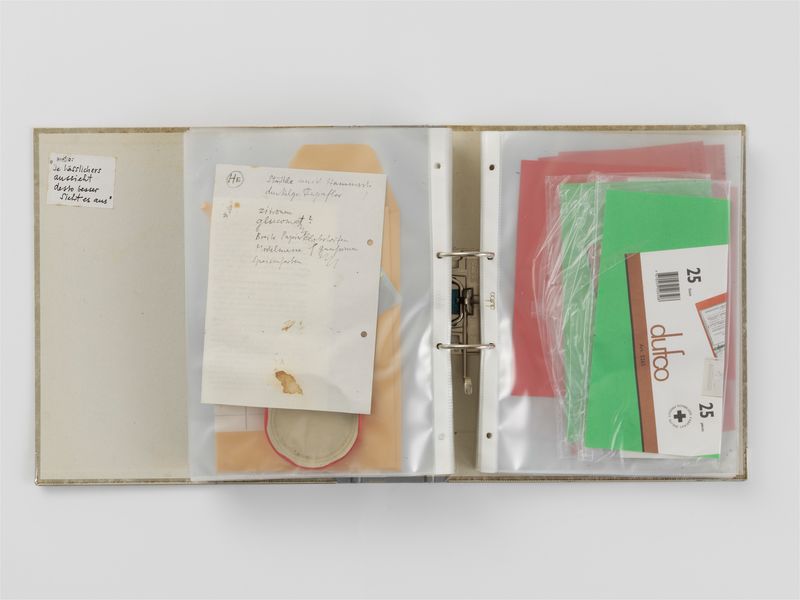

Dieter Roth, Flacher Abfall (Flat Waste) 1987 © Dieter Roth Estate

Installation view, ‘Dieter Roth. Paper’, Hauser & Wirth Zürich, 2018

I try to portray the world as something that is seen by me. That the reports and all the things we believe exist—the objects, events etc.—are nothing but stuff that springs from my own lips.

And you don’t try to think things through afterwards either?

I haven’t looked at that for a week now. I can’t let myself look at them at all. But I know that when I look at them a month later, I’ll find them simply wonderful things to sell and everybody falls for that. You see? I like them myself, when I’m a bit more drunk, I think they’re beautiful. Then it makes me happy to look at them. But not while I’m drawing them.

If you had to come up with some reason for there being two figures instead of one—do you have any thoughts on that? Any explanation?

Nope.

You don’t want one? Are you deliberately avoiding that?

Yes. When I’m sitting here alone, for sure. Because explanations like that only come up when people talk to one another. Explanations like that are verbal phenomena. I don’t need those when I’m alone. Well, of course they’re needed, but the concentration is so intense, and I’ve trained myself over the course of many, many years of just sitting alone, not to get into that kind of conversation with myself. That just makes me unhappy. Like, you have to find something out, you have to push yourself, you have to keep pushing your vision. You see something double and have to find a sentence to fit, or some kind of explanation. What you have to find is nothing but a sentence. So you have to give a clear form—to something unclear. You have to become worldly and you have to work, and I dread that work—all that mind work with its verbal expression or whatever you might call it. For me, language isn’t a form of expression anyway. It’s just a formulation of something that comes from within and simply takes effort. It stirs a sense of utter dejection.

Does that mean that drawing and writing are in essence different? Two completely different activities?

Nope. I’m the same with writing. Nowadays, for sure. I’ve trained myself to do that too. I write best when I’m hungover and alone.

Do you also write without looking and without reflecting?

Yes. I just write as it comes.

And what you just described as ‘mind work’—is that something else; a different kind of activity?

Yes. That’s something that happens between people. That’s about operating the dreadful language mechanisms, the vast language machine we’re sitting in.

Have you never written about art or other artists, or written essays and suchlike that would fall into the category of ‘mind work’?

Sure, I’ve done that on occasion. But it takes effort. I hate that. It makes me unhappy and it all seems so false.

And your diaries—which category do they fall into?

Neither. I think the diaries are mainly an attempt to express a lamentation, a trenchant shriek of pain… a loud and trenchant invocation to weep, you know—so that people howl and cry when they read it. For me, it’s about empathy, about lamentation.

Yes? But you write them first and foremost for yourself—or do you write the diaries for others?

But of course I’m assuming somebody will read them. I’ve even read passages out to certain people, with great success. Well, they were almost in tears. That’s always a good sign for me. (Laughs) But, as I said, it’s… it’s a mixed bag. I’m always trying to be like the legendary ‘Brave Little Tailor’ (Grimm’s fairytale) who killed as many flies as he could in one fell swoop. Swat!

So what is the theme of these diaries?

I try to portray the world as something that is seen by me. That the reports and all the things we believe exist—the objects, events etc.—are nothing but stuff that springs from my own lips. So to speak. Nothing else. Poured into your ear. But what actually happens, is a different matter.

Dieter Roth in his studio, 1990s © Dieter Roth Estate

How do you manage to deny the reality of everything that isn’t yourself? By saying ‘that doesn’t exist at all‘ or by saying ‘that’s beyond my grasp‘?

I don’t know—I wouldn’t want to claim that it doesn’t exist. I just want to assert that what we say is nothing more than what we say. Even what I’m saying now—there’s no certainty that I actually thought it. It’s just something I’m saying now. Who knows how people think? Who knows what you’re thinking now? Impossible to tell. At most, all you can see is what you say, and not even that; because when you say something, you’ve only heard it. You don’t know what you say—you have to hear it. And when you hear it, then you don’t know what you have said, because you only heard it. And that’s what I find saddest of all. I find that saddest of all, and that melancholy is so… I find it so pleasant that I’m now going to try—I don’t know for how long—to compose songs of lamentation about this melancholy. There are various technical means that I’ve devised, and I’m going to use them. And the tears will flow. I hope.

What kind of technical means?

Well, there are already certain existing forms of lament: sonnet, ballad, and all those things. Then there’s classical music. There are lots of things which, when you apply them—that is, when you apply certain formal rules—you can expect them to elicit a certain sentiment automatically. Such as when you listen to Beethoven; it makes you feel a little sad. Something like that. And I think I can say that I’ve been trying for a long time, for years. The main thing for me has always been literature, so-called fiction and poetry. And I’ve tried to lend some kind of form to this feeling—sad and despairing, yet at the same time sweet—that I have in life. So that the people who read it also feel that sweet sadness. And then I realised, that this happens most strongly when I try to write as succinctly as possible. When you’re young, you tend to just go yum-tee-tum and write in an adolescent style with florid language. And I’ve come to realise that it doesn’t work at all. What really hits home is saying something as succinctly as possible.

But the way you write is… well, I wouldn’t exactly call it succinct—

But in the diaries I am, absolutely, succinct. That’s what has the biggest emotional impact of all.

And this melancholy that overcomes you because what you say is nothing but what you say: does that sadness come from a feeling of being trapped? Not being able to communicate? With others, or with yourself?

Yes, there’s probably something of that in it. It’s the sense of sadness that nothing can be said. Well, when we say something to each other, it isn’t that we—this is all so crude!—well, that we are communicating something, but that we… we’re hypnotising one another. That’s what it is. Language—it’s a technique of hypnosis. It’s not a means of communication. It’s just about tactility, as McLuhan—what’s his name again?— Marshall McLuhan, would put it.

So what do you think happens when people speak to one another? Is it an erotic relationship in your eyes, or is it a power struggle?

Whatever it is, I do think it’s something sad. It’s meant to move us to tears.

Why?

So that we can be happy.

Aha. Now you’re jumping the gun again.

So that I can avoid the explanatory mechanisms that are being brought out again, by you. Got that? Am I right? Did I spot that correctly? Did I spot the danger in time?

Where do you see the danger in this?

I find that the life I’ve led so far, which has always involved explanations and portrayals, is still completely entrenched in some shit or other. People… Well, I’m really just going through the motions of a ritual, performing a ritual that has been imposed on me by a bunch of idiots.

What are you talking about now? About the interview situation?

No. About language in general. Take this here—we’re talking, aren’t we? I mean, the interview situation is just a drop in the ocean, in my view. It’s just going through the motions of some… it’s like when a Catholic kneels down and chomps on that matzo or whatever the thing is called and says this is the body of Christ, and stuff like that; then we think: what a load of nonsense. But I’m sure—in fact I could swear, because, believe me, that’s just how I am—I can see it when we talk to each other. I can see how we are celebrating our Last Suppers here. It’s all just a formality. I don’t see anything but that in it.

And that’s so beautifully sad. Being able to shed such tears is something to be happy about! That’s the delight of life: seeing how the things we believe exist don’t actually exist and how we believe we’re talking about something and find that doesn’t actually exist either, so we can’t even talk about anything, and that makes us ever so sad, and that sadness gives you such a… doped-up effect. And that’s the effect I’m looking for right now. Well, how does that sound? (Pours a beer)

Irmelin Lebeer-Hossmann is a freelance author and publisher based in Brussels. The above excerpted interview took place Hamburg, 28 – 30 September 1976, and Stuttgart, 20 – 22 June 1979. Conducted in German, this interview is published in English for the first time with translations by Ishbel Flett and Malcolm Green. Barbara Wien was born in 1953 in Munich and works as a gallerist, editor, and publisher in Berlin. She worked for Dieter Roth between 1985 and 1987, and planned the publication of the Dieter Roth Collected Interviews in collaboration with the artist. Published by Edition Hansjörg Mayer, London, 2019, Dieter Roth Collected Interviews is now available from Thames & Hudson worldwide.