Essays

Oudolf Field and Durslade Farm

by Tania Compton

Anri Sala, Clocked Perspective, 2012. Installation view, Oudolf Field, 2014 © Anri Sala. Photo: Heather Edwards

Anri Sala’s Clocked Perspective (2012) towered over Oudolf Field when Durslade Farm first opened to the public in July 2014; the installation’s spinning hands echoing the dynamic activity of the 26,000 rapidly growing plants beneath it. That September, when the garden was officially opened, the outer beds of Piet’s planting had grown as tall as the Dutch maestro of perennial planting himself.

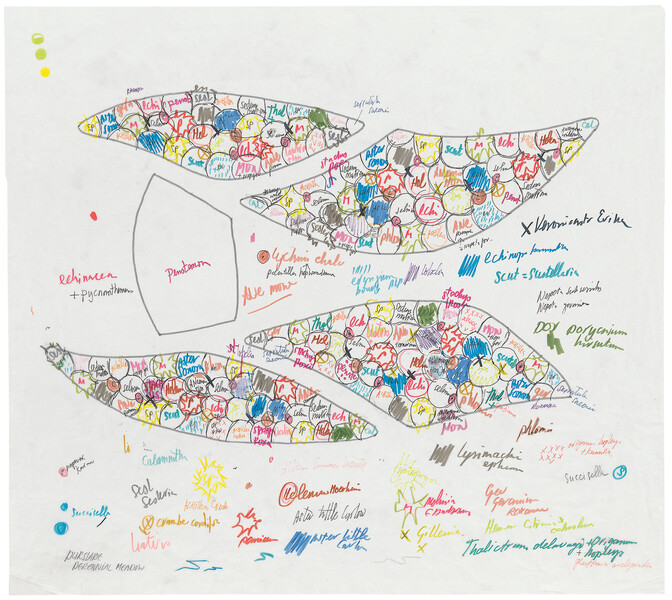

Piet’s tracing paper plans had been used to transform a bare rectangle of pasture into a triumphant three-dimensional display of colour, form, and texture. The multicolour blueprint for this garden came to Piet in a moment of confidence working in his studio in Hummelo. The original plan – with its Lichtensteinesque bubbles and lightning strikes accompanied by hieroglyphic botanical shorthand – has joined other treasures from Iwan and Manuela Wirth’s personal collection on the walls of Roth Bar & Grill. Among works by Martin Creed, Pipilotti Rist, and Jason Rhoades, Piet’s drawing speaks to the epicurean ideals that underpin this space where art, nature, and food mingle without hierarchy. Piet had three main spaces to compose: the farmyard, the cloister, and the field. The farmyard is fluid and simple – a smooth, open rectangle of mowed lawn trimmed with bugle and oxeye daisies, which make silhouettes on the gallery’s calico blinds. A quiet border of grasses and perennials outside the office accord with the exquisitely restored farm buildings that remain the focus of the area. That is, until the circus comes to town for Hauser & Wirth’s Summer Party in July of each year, when the farmyard becomes overrun with candy-striped big tops, cider-selling double-decker buses, merry-go-rounds, clowns, and jugglers.

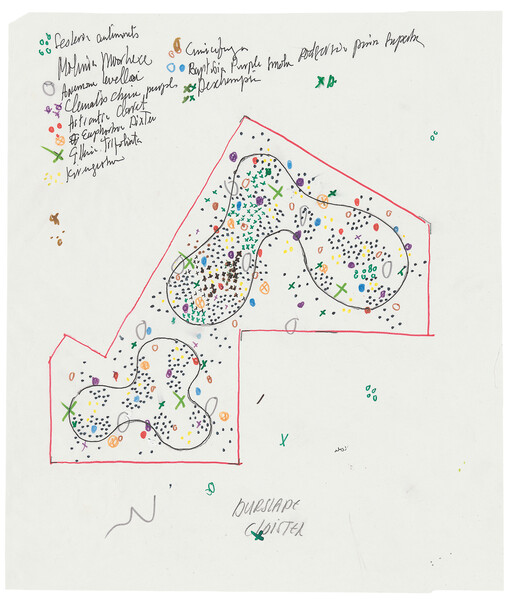

Landscape sketch for the Cloister Courtyard by Piet Oudolf, 2012

Landscape sketch for Oudolf Field by Piet Oudolf, 2012

The Cloister Courtyard is spare and stripped back; a palette of green with pops of muted colour. Light filters through the canopy of asymmetrically arranged paper mulberries (Broussonetia papyrifera) and the graduated mounds of underplanting that rise out of lime-green Sesleria autumnalis. This is a space that begs one to sit and slow down. It has the meditative effect of a Japanese garden; gradually revealing more detail if you stop and take time to look. Delicately upright Gillenia trifoliata with wispy white flowers and horizontal layers of Kirengeshoma palmata leaves topped by delicate pale yellow bells in late summer, globes of grey-green baptisia leaves and feathery plumes of deschampsia, accents of bronze- leaved actaea, and injections of blood-red astrantia are set against the bare walls of restored buildings and the clean simplicity of Luis Laplace’s square-columned colonnade. The interplay between the solid stone of the architecture, the canopy of indented trilobate leaves on the paper mulberries, the perennials, and the grasses is intensified by the defined space between these separate compositional elements.

The courtyard planting also acts as a gentle juxtaposition to the sculptures that occupy the cloister; whether the plants are invaded by the legs of an overarching Louise Bourgeois spider, fanned by a gently swaying Alexander Calder mobile, or towered over by Marcus Coates’ edible, apple-armoured scare-crow. From the melodious quartet of the Cloister Courtyard, a view opens across one of the gallery spaces to Oudolf Field, which is abuzz year-round with visitors, plants, birds, and insects. The field is a cymbal-clashing tuba-booming bonanza in the summer; in the winter, it diminuendos into a texture-laden tapestry of golden brown and black. For Piet, the burst of colour from flowers is only a momentary interlude in the yearly cycle of a plant; subordinate to their intrinsic form and structure. He maintains that any planting should have enough variety of shape to look interesting in a black and white photograph: ‘Looking at it again in colour should add another dimension, but a secondary one.’ The summer visitor to Oudolf Field will get a shock of excitement when the garden is in full bloom, but it is the repeat visitors – the staff, the local community, the artists-in-residence – for whom the garden takes on greater resonance, and who are unanimously swept away by its beauty in the winter.

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1994 © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, New York/DACS, London. Courtesy The Easton Foundation and Hauser & Wirth. Jenny Holzer, Survival Series: In a dream you saw..., 1989 © (2017) Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Installation view, The Cloister Courtyard, Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2015. Photo: Heather Edwards

Catherine Goodman spent the harsh winter that saw in 2018 as the Durslade artist-in-residence. She observed how ‘even in the deepest winter, with snow on the ground, the garden was like another gallery, always very welcoming, with people who would come just to walk around it.’ Many public gardens tend to shy away from scrutiny in the winter months and are often hidden from view between October and March, but Oudolf Field remains open throughout winter when according to the designer Dan Pearson, the garden ‘is arguably at its best. Like a negative, it allows you to see in another way, and to read a layer of Piet’s expertise which is at play when most other gardens are spayed and tattered.

Then, the garden has structure and detail, luminosity, and the necessary darkness. Though pared back, it is far from monochrome in the dark months.’ From pale straw to darkest burnt umber, gentle mushroom pink to deep black, the winter colours are balanced by the trace of their silhouettes. Piet pairs line with mass, solid with void, shape with colour. He can visualise an encyclopaedia of plant combinations as they change throughout the year, creating masterly couplings of ornamental grasses and perennials. In the first four beds of block planting, Helenium ‘Moerheim Beauty’ is offset by Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, Echinops bannaticus by Molinia ‘Edith Dudszus’, and Phlomis russeliana by coriander-scented dropseed pasture grass. In her introduction to Piet and Michael King’s 1999 Gardening with Grasses, the late Beth Chatto likened grasses to the ‘adjectives’ of a mixed planting, ‘that soften your statements, or make them sparkle.’

For Piet, grasses are more a verb than an adjective. They are the integral ingredient that underpins all of his work – from large-scale commissions such as New York’s High Line to Oudolf Field. Grasses are the conduits that activate Piet’s desire to conjure an evocation of nature in his compositions. As he has often said, ‘My biggest inspiration is nature; I do not want to copy it but to recreate the emotion.’ At Durslade, grasses are the amulets, mascots, and totems woven through Piet’s plantings. In the meadow areas, Sporobolus heterolepis flows in counterpoint to the staccato chimes of Echinacea pallida or Dianthus carthusianorum. The fluidity of the planting relies on this interplay throughout the seasons; from long, low pools of blood grass (Imperata cylindrica ‘Rubra’) to giant swaying sprays of Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’.

The composition of Oudolf Field does not rely on a hierarchy of importance. Instead, it insists that all moments are potentially interesting and that the endlessly mutable combination of parts is the most affirming and awesome representation of the living world. And it is here, in its compositional strategy, that Oudolf Field expresses its politics, which are inclusive and egalitarian.

As Piet has described, the overall effect of the garden is augmented by the changing perspectives that are granted to the visitor as they follow its meandering paths. These serpentine lines weave between the seventeen asymmetrical island beds that are gently mounded with earth to intensify the sense of rhythm, but which are never so high as to block sightline. The effect is that from every perspective, one experiences Piet’s planting in great sweeps of immersive pattern and depth. Zigzagging along the paths through Oudolf Field is a kaleidoscopic experience, like walking through a three-dimensional version of a Pipilotti Rist film. Unsurprisingly, these spaces are universally loved by children. Their reaction is an unfettered barometer by which to judge the success of any garden.

The author and architectural historian Pippa Thistlethwaite, who is a regular visitor to Durslade, remembers her seven-year-old granddaughter’s first plea to use granny’s camera as she became absorbed by the shapes and colours of Oudolf Field. To artist Mike Glier, who visited for a summer residency in 2017, the planting brought to mind ‘a field painting by Pollock, Rothko, or Mitchell.’ Glier commented that ‘the composition of Oudolf Field does not rely on a hierarchy of importance. Instead, it insists that all moments are potentially interesting and that the endlessly mutable combination of parts is the most affirming and awesome representation of the living world. And it is here, in its compositional strategy, that Oudolf Field expresses its politics, which are inclusive and egalitarian.’

Oudolf Field views, August 2014. Photo: Heather Edwards

This absence of hierarchy spreads beyond the confines of the planting at Durslade. In its entirety, the atmosphere leaves one with the impression of a collaborative installation where each facet of the project buttresses the others. An aerial view of Durslade would show chefs outside stoking fires, roasting spits of meat procured directly from the farm, and kitchen staff cutting borage and mint for cocktails, tending raised beds of plump salad leaves and herbs, and washing freshly- pulled carrots in the spring water that feeds the garden before its return to the water table. Surrounding all this activity, the gallery spaces reside like quiet, contemplative chapels.

Across the farmyard in the gallery’s office, future exhibitions are plotted alongside funfairs and fiestas. And somewhere within this imaginary bird’s-eye view is the gardener Mark Dumbleton among a pointillist scattering of visitors moving about in his choreographed swathes of plants. Mark started work at Durslade in time for the garden’s opening, when Piet emphatically stated that ‘All my work depends on gardeners 100 per cent, without gardeners, you lose this in a few years.’ Now in its fourth year, Piet’s constantly evolving tapestry is far from lost. Unlike the Henry Moore or Alexander Calder hangings that have been shown in the galleries, the garden is a tapestry whose threads are unpicked each year, with travelling fibres that need corralling back into place, so their effect remains as intended.

Mark is a kind of curator and conservator, constantly judging the balance of form and flower, intervening when necessary to separate the stoic, solid plants that keep to their positions from the gradual colonisation of the stealth operators like devil’s bit and Macedonian scabious, the moor grasses, or camassias, which are planted in their thousands. As a round-the-clock gardener – who would be quite happy just to get on without interruption – Mark is under constant scrutiny. He laughs knowingly at the idea of being a modern-day equivalent of a garden hermit, or perhaps a kind of performance artist, tending one of the many jewels in the Durslade crown. Between the volume of visitors and the outlook granted by the open, sloping site, the luxury of hiding is only afforded to Mark if he is working at the garden’s outer borders.

As Piet loves to say, ‘It is amazing what a plant can do to your mind.’

Before the garden was planted, there were mutterings from local ecologists that exotic plants would be detrimental to pollinators. The inverse has happened, and Oudolf Field has become an entomologist’s, lepidopterist’s, and ornithologist’s paradise. When Mark found a nocturnal slug and snail-devouring violet ground beetle, he knew that the ecology of the garden was in good harmony. Oudolf Field is inhabited by an abundance of bees, hoverflies, butterflies, and moths, none of whom seem to care whether the plants they feast on have a British passport. Birds are likewise unbiased. The slope from the Radić Pavilion feels like a swallow runway, as these summer visitors swoop down to the pond.

Mark arrived one morning to find the bleached stems of Succisa pratensis smashed to the ground. At first, he thought a fox had got in, only to spy a family of finches feasting further up the garden. Goldfinches, greenfinches, linnets, and wrens use the garden as their larder, thrushes break open snails on the paths, and a lone, proprietorial crow visits as the garden closes each day for a saunter up and down the weaving paths, as though inspecting Mark’s work. Mike Glier tapped into the avian presence when he went to draw in the garden. ‘I preferred visiting the garden on Mondays, when it was closed, and my greediness for the place was unchecked by the necessity of sharing. One foggy morning, the heavy dew settled countless droplets on each leaf and stem.

As the sun rose, each drop became a prism, and the garden sparkled as if auditioning for a Disney film. The garden smelled sweet and spicy. Like a performance by John Cage, the sound was a mix of found melody and percussion. The birds commanded the score both as soloists and chorus; twittering, chattering, and fluttering with occasional outbursts of rustling as they skirmished in the underbrush. Sheep were complaining in the field beyond, as were the occasional jet engines overhead. If breezy, the susurrus of leaf on leaf was a constant. And when Mark, the head gardener, started the power mower, my god, what drama!’ The work Mike made at Durslade ‘moved happily between naturalistic observation and abstraction, an approach that in some ways paralleled the design of the garden. While nothing feels more real than a single flower, the garden itself is a marvellous abstraction.’

Oudolf Field in September 2015. Photo: Heather Edwards

Oudolf Field in November 2014. Photo: Heather Edwards

Tom Piper had just started filming Five Seasons: The Gardens of Piet Oudolf when Piet was commissioned to make a plan for Durslade in 2011. Tom remembers: ‘When Piet first told me it could be the project I could follow in real-time, he said he felt, already, it would be his best garden yet, possibly his ‘masterpiece.’ I think his optimism owed as much to his belief that Iwan and Manuela were going to be very supportive and afford him a lot of freedom in the design. I think that bore out, and that it’s indicative of their relationship with their artists in general, and, most importantly, that they genuinely viewed Piet on that same level – as an artist of the gallery, not merely someone they were “hiring” to deliver them a garden.’

This hypothesis was borne out at a dinner in the winter of 2017, when the Wirths spoke publicly for the first time about their collecting life. As is customary for events at Durslade, those present were an eclectic blend of visiting artists, friends, locals, and teachers who work in the town’s many schools. At the dinner, 100 people were seated between five tables, each of which were asked to nominate a work the whole table agreed was their favourite among those hanging on the restaurant walls. One table chose Piet’s plan. Their nominee said that not only was the plan a work of art, but that what they unanimously loved was the world that it conjured. This simple sheet of tracing paper was a potent symbol of a much bigger picture, tapping into the promise of sun and frost-rimed grasses, and beyond, to the interconnectedness of growth and decay. This was a plan that represented a new beacon, not just for the people of Bruton. As Piet loves to say, ‘It is amazing what a plant can do to your mind.’