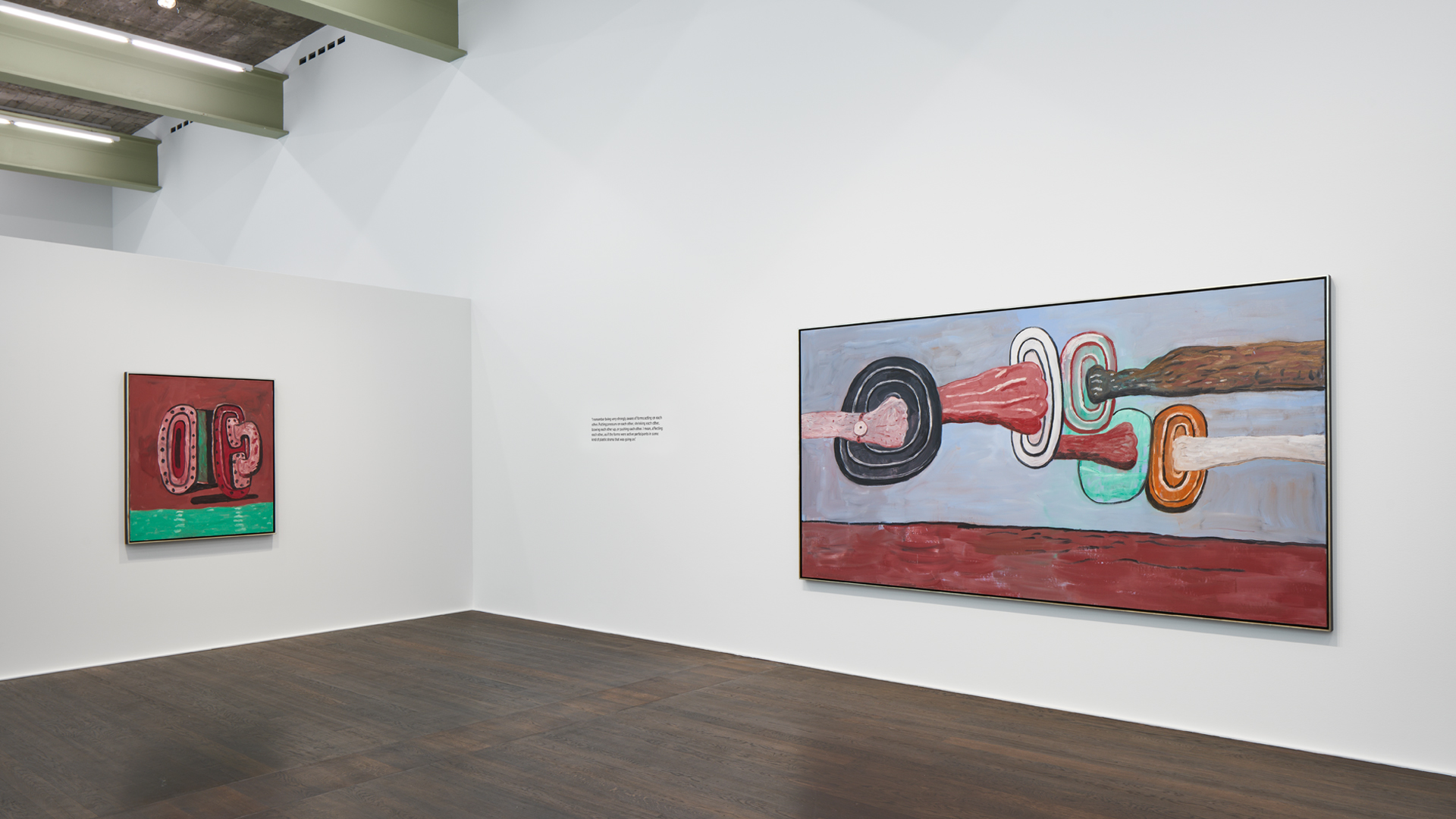

PHILIP GUSTON

SINGULARITIES

7 JUNE – 28 SEPTEMBER 2024

ZURICH, LIMMATSTRASSE

Curated in collaboration with Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter and President of The Guston Foundation, this exhibition at our Zurich gallery presents well-known paintings alongside never-before exhibited works, all dated between 1968 and 1979, that explore the liberated motifs and instinctual forms that emerged in Guston’s late works as they continued to evolve until his death in 1980. Opening during Zurich Art Weekend 2024, this exhibition follows the major retrospective ‘Philip Guston’ at the Tate Modern, which closed in February 2024.

EXPLORE THE EXHIBITION

The strange forms that inhabit the 12 paintings in this exhibition of Philip Guston’s late works are intensely personal and packed with imagery that haunted the artist throughout his painting life. Yet they also speak to us in a metaphysical language that resists analysis, but that we grasp deeply, intuitively.

When asked, Guston would resist interpretating the iconic symbols that appeared in his paintings. He would respond that he, too, was mystified by these inexplicable forms, these singularities. ‘If I speak of having a subject to paint,’ he wrote, ‘I mean there is a forgotten place of beings and things, which I need to remember. I want to see this place.’

‘I really only love strangeness.’—Philip Guston

From this forgotten place emerge the artist’s singular responses to the beauty, pain and cruelty of the world, to the intimacies of his daily life, love and the passage of time and loss. These works are neither cerebral nor removed; they are timeless. And they feel alive, as if freshly painted. Complex surfaces disclose an exuberant love of the act of painting itself, Guston’s fidelity to an ancient process cultivated over a lifetime of close observation and rigorous interrogation of the art he loved and the necessity of painting.

‘A painting feels lived-out to me, not painted. That’s why one is changed by painting. In a rare magical moment, I never feel myself to be more than a trusting accomplice. So, the paintings aren’t pictures, but evidences—maybe documents—along the road you have not chosen, but are on nevertheless.’

Relic

1974

Guston loved the mundane, the poetry of ordinary objects that transform and reappear, taking on multiple meanings. As he worked, previously unknown parts of himself began to take shape. In ‘Painter's Forms’ (1972), the artist, in profile, coughs up his talisman objects (shoe, bottle, boot, easel, cigarette) into the actual world. It is a painting about the act of painting.

The evocative ‘Relic’ (1974) calls to mind the foot of some ancient statue whose body has been lost to the ravages of time. Guston was fascinated by ruins and especially by disembodied parts of colossal Roman statues.

Four years later, in ‘Feet on Rug’ (1978), the disembodied feet of ruins have been transmuted into actors in a surreal allegory. Are they, too, evidence of loss, of times past?

Feet on Rug

1978

Future

1978

In ‘Future’ (1978), a despairing human figure sinks into a post-apocalyptic red ground or sea dominated by the surviving creatures: a rotating bug-amoeba form seems to cut through the red sludge as a snail-like creature advances.

In ‘Untitled’ (1969) an earlier version of this snail form, nautilus-chambered, curls its way into a cozy but colorless domestic interior. Next to it hangs another work from the same year with an equally enigmatic allegorical theme. In ‘Untitled’ (1969) some sort of reckoning appears to be taking place. Beside a dark window, a gloved hand points down at an orb that might be a soccer ball or a globe. A hand intervenes from the side.

‘It is a real place to me, this world I am painting. I feel as if I lived there, its forms defined. All I really need is time and more time to ‘reveal’… I pretend I am away (and so I am!), all sorts of tricks to gain the necessary continuity of TIME.’—Philip Guston

Door and Room

1978

It was during the Second World War that Guston first painted masked children playing war games, with sticks for lances and trash can lids as shields. These mock battles surfaced repeatedly during the war years of the 1940s, reappearing in allegorical form in his late works. These paintings refence not only the ceaseless struggle and conflict of the world, but also are evidence of the artist’s fascination with complex battle scenes in art, especially Paulo Uccello’s great ‘Battle of San Romano.’

Even before the late figurative work emerged, when his paintings were still seen as abstract, Guston had invited and cultivated this dynamic gathering of forces: ‘I remember being very strongly aware of forms acting on each other. Putting pressure on each other, shrinking each other, blowing each other up, or pushing each other. I mean, affecting each other, as if the forms were active participants in some kind of plastic drama that was going on.’

The open door in ‘Door and Room’ (1978) suggests a forced entry into the artist’s studio. The realities of the world intrude into that sanctuary, leaving the artist as witness to the perpetual wars we all experience. The red and black scene is relieved only by the narrow strip of blue at the top, like a slight breath of air or a hope for peace. Yet in the red field of combat are unmistakable signs of a painterly, exuberant celebration of dynamic form and color.

There was something infinitely compelling to Guston about conflict and struggle, and even evil. It was the real world that engaged him, what he termed the ‘big subject matter.’ In a 1972 slide-talk to students, he confessed that when he returned to Italy after first exhibiting his late work, he first went to see the paintings of the past that he loved. But not for their beauty.

‘Guston… had strived to paint what he thought a man was—a sum of his everything. He said both in words and in numerous paintings and drawings that he was himself, as any artist is, the witness, the critic, the stranger, and most of all, his own judge and his own jury. No painter could have been more unsparing, as juror and judge, than Guston himself in his last resounding works.’—Dore Ashton, art historian and critic

Aegean

1978

‘I wanted to see early frescoes of Last Judgments and end-of-the-world paintings. Particularly Romanesque paintings and Sienese fresco painters who paint huge, marvelous frescoes of the damned, all the tortures in hell, and so on. Heaven is always very dull, just a lot of people lined up. Like trumpets, they’re all lined up. There’s not much to look at. But when they’re going to hell the painter really goes to town. All kinds of marvelous stuff. That’s when they really enjoyed painting. I feel we live in comparable times. Oh yeah, and I want to paint that. I don’t want to copy, but I feel that’s the big subject matter. I don’t know how it’s going to come out. Well, I’ve begun. I’ve begun with this story.’

‘Agean’ (1978) is one of Guston’s largest and strangest works. The battle takes place against an implacable blue sky. In mid-air, oddly formed arms and hands advance with shields. There is a feeling both of unease and stasis, as if these non-human limbs are locked in their aggressive posture. The title may refer to the Aegean Sea, the site of many battles, ancient and modern. In ‘Untitled’ (1979) locked in perpetual struggle, the trash-can lid shields have merged into a single richly painted iconic form, energized and hovering midair over a lime green sea.

‘I wanted to include everything. I felt, like everybody, disturbed about everything to such an extent that I didn’t want to exclude it from the studio, from what I did. Paint it. I didn’t think I was illustrating anything.’

In studded circular forms, the primal wheels in two untitledworks from 1969 seem ruined or deformed, yet clearly on their way to a destination. They are emblems. Or given that the dashes suggest fenders, they may be precursor elements of later works, jalopy wheels from the Ku Klux Klan cars that were soon to emerge. Or both. Archeologists tell us that the earliest stone wheel has been dated millennia before the Christian Era and was found in Mesopotamia over six thousand years ago.

Text by Musa Mayer

Musa Mayer on the work of Philip Guston

SERIOUS PLAY

In a new film presented by Ursula, Musa Mayer takes us through the life and work of her father, the artist Philip Guston, whose variation in style over the years embodies his belief in the importance of learning to have the capacity to change, and his willingness to engage in the ‘serious play, which we call art’ that ‘can’t be static.’

ON VIEW IN ZURICH, LIMMATSTRASSE

‘Philip Guston. Singularities’ is on view from Tues - Sat 11 am – 6 pm through 28 September at Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse.

Related Content

About the Artist

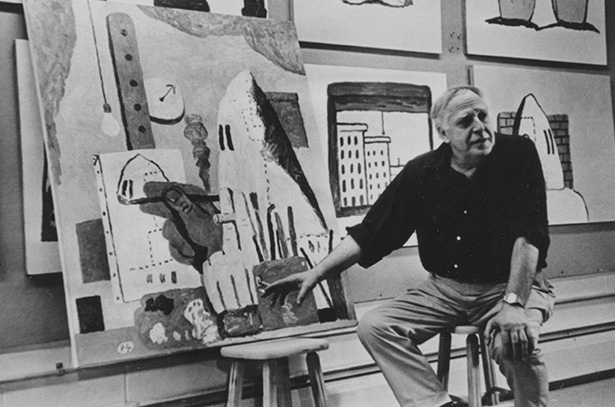

Philip Guston

Philip Guston (1913 – 1980) is one of the great luminaries of twentieth-century art. His commitment to producing work from genuine emotion and lived experience ensures its enduring impact. Guston’s legendary career spanned a half century, from 1930 to 1980. His paintings—particularly the liberated and instinctual forms of his late work—continue to exert a powerful influence on younger generations of contemporary painters. For an in-depth overview of his career, click here.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 11