Hauser & Wirth Zürich presents an exhibition focused on Henry Moore’s early works on paper relating to myth and poetry. Including poetry magazine covers, illustrations for poems by Herbert Read and sketches of the Prometheus myth, the presentation explores the graphic side of Moore’s practice and provides an insight into his relationship with the literary world. In addition to etchings, lithographs and drawings, several sculptures are also on view including a large-scale work carved from Elmwood that has not been exhibited since the 1950s. Most of the works were created in the years surrounding the end of World War II; supporting archival material, such as the artist’s tools, photographs of his etching studio and correspondence with friends such as W. H. Auden and Herbert Read, offer intimate access to this period in Moore’s career. ‘Myths & Poetry’ has been organised in collaboration with the Henry Moore Foundation and is curated by the artist’s daughter, Mary Moore.

Due to the uncertainty brought by war, in 1940 Moore relocated from Kent and London to Hertfordshire. This move forced him to abandon sculpture for two and half years, shifting his focus to drawings and works on paper. A significant project that emerged from this period was the book Prométheé – André Gide’s adaptation of Goethe’s Prometheus, illustrated with Moore’s lithographs and typography. During a trip to Paris, Moore had been invited to contribute to the publication by French typographer and publisher, Henri Jonquieres. The artist produced eight lithographs alongside the cover, title page and letters to begin each chapter. The exhibition presents a group of drawings found in related preparatory sketchbooks (1949 – 1950) where each page is quartered into a sequence of four smaller drawings. Fine works in their own right, they also illuminate how Moore explored the new possibilities for sculpture, most significantly the male figure, something previously unseen in his practice. The drawings present new shapes, forms and textures, each page littered with annotations detailing how the figures could be realised in bronze or clay.

Moore’s characterisation of Prometheus defies the traditional gothic horrors where he is portrayed as figure of anguish, suffering eternal torment tied to a rock. In Moore’s hand, Prometheus is gallant like the stoic warriors of ancient Greece; he stole from the gods to help mankind, unperturbed by the punishment that he might have to endure as a result. For example, in ‘Prometheus Defiant’ and ‘Prometheus on the Rocks’, the figure – with a broad torso and svelte limbs typical of Moore’s work – stands tall, bold and measured. The muted tones of the wax-crayon and watercolour wash produce a charged yet calm atmosphere. Moore also employed the ‘two-way sectional line method’ that he developed in his etching studio: a grid of horizontal lines follow the curves of the figures, emphasising their three-dimensional form and allowing him to create depth without shadow.

The large-scale bronze ‘Warrior with Shield’, created in 1953 / 1954 shortly after the Prométheé project and following a trip to Greece in 1951, was the first single male figure that Moore carried out in sculpture. As implied by its title, the work is classical in arrangement and the twisted, tense and amputated torso, with only a shield for protection, calls to mind the brave swordsman succumbed to brutal battle-wounds in Homer’s epics. Moore explained in a letter that ‘at first the figure was reclining. A day or two later I added a shield and altered its position… so it changed from an inactive pose into a figure which, though wounded, is still defiant […] I think The Warrior has some Greek influence, not consciously wished but perhaps the result of visit to Athens and other parts of Greece’. Indeed the broken limbs echo the fragmentary nature of surviving Greek antiquities that Moore would have encountered on his visit to Greece, and perhaps too from visits to the British Museum. In spite of this, ‘Warrior with Shield’ is also decidedly modern – created in the aftermath of World War II, it discloses an overt concern with the mutilation and miseraries of contemporary war. Art Historian Christa Lichtenstern has suggested that the shield, which gives protection from above, alludes to the aerial bombardments of the war, subsequently linking Moore’s warrior sculptures with his earlier Shelter drawings and those made for Edward Sackville’s The Rescue. When talking about the inception of ‘Warrior with Shield’, Moore said, ‘It evolved from a pebble I found on the seashore… which reminded me of the stump of a leg, amputated at the hip. Just as Leonardo says somewhere in his notebook that a painter can find a battle scene in the lichen marks on a wall’.

The female figures in the Prométheé drawings (1949 – 1950), such as in ‘Statues Dispersed through a Grove’ and ‘Statues and Draped Figures’, incorporate drapery marking another subtle classical delineation that would later come to feature in his sculpture. For example, ‘Standing Girl’ (1952), carved from Elmwood, and ‘Draped Reclining Figure’ (1952), moulded in bronze. Drapery had already played an important part in the Shelter drawings; he began to learn about its function as form and it encouraged in him the intention to use drapery in sculpture in a more realistic way. The Prométheé drawings helped strengthen this intention. ‘Drapery can emphasise the tension in a figure’, Moore said in 1954, ‘for where the form pushes outwards, such as on the shoulders, the thighs, the breasts etc., it can be pulled tight… and by contrast with the crumpled slackness of the drapery that lies between the salient points, the pressure from inside is intensified […] It need not be just a decorative addition, but can serve to stress the sculptural idea of the figure’. So, whilst direct interpretations of classical narratives never featured in Moore’s sculpture, ancient civilisation and the European Renaissance still provided a point of inspiration and the Prométheé drawings marked the beginning of this interest.

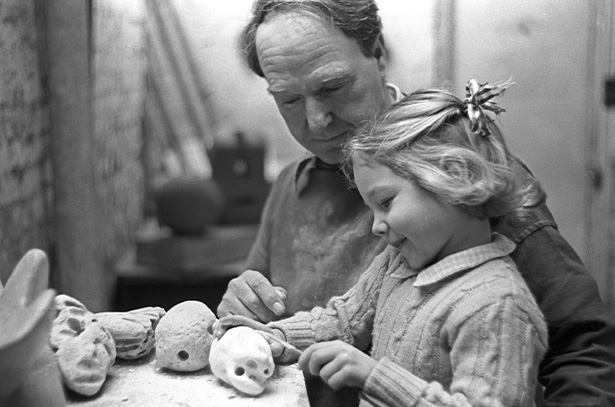

Throughout his life Moore enjoyed poetry and surrounded himself with friends and artists that shared and discussed their writing with him. Moore and art critic Herbert Read had been friends since the early 1930s, having met in Hampstead where they both lived. The development of their respective work as critic and artist was entwined for nearly 40 years: Moore had a profound impact on Read’s aesthetic politics; Read cemented Moore’s legacy as Britain’s most important modern artist. In 1945/6 a collection of Read’s poems were released and at the request of the publisher Moore was asked to create a lithograph in response to a particular poem, ‘They Came Running’ (1945). The exhibition displays a collection of Moore’s drawing studies for the lithograph, in which the artist perfectly captured the conflict between the naive joy of childhood and the dark, existential angst of the adult world. The dark ominous sky and barbed wire littered on the beach act as a bleak reminder of man’s propensity for conflict.

Beginning in 1937, Moore contributed illustrations to two modernist literary magazines: Poetry London and Contemporary Poetry and Prose. The magazines featured verse and criticism by Moore’s friends and acquaintances such as W. H. Auden, Herbert Read, Stephen Spender, and Dylan Thomas, as well as leading international figures including Paul Éluard and Salvidor Dalí. Moore was one of several artists, including Hans Arp, Paul Klee and Max Ernst, invited to design the cover for individual issues and presented here is a collection of his design prototypes. ‘The Lyre Bird: Cover Design for ‘Poetry’’ (1942) is a joyful and graphic watercolour depicting a group of Lyre birds, known for their ability to mimic sound. The cover designs for Contemporary Poetry and Prose (all 1937) feature abstract pen and ink drawings – dynamic black lines overlaid on bright inky shapes play with positive and negative space to conjure figures and mythical forms. The sharp, geometric qualities of the illustrations that Moore produced for both publications are unlike any of his other works on paper. Moore recalled being invited to illustrate a collection of Auden poems slightly later in the 1970s. He said ‘When Véra Lindsay suggested that I illustrate a selection of Auden poems I was at once interested in the idea, because I had known him since the 1930s and had always greatly admired him and his poetry, but it was some months before I could really get going. I began… in a straightforward way as if I were illustrating Alice in Wonderland or any other story. But after reading some of the poems I realised it would be impossible to treat them in the same way and I began to wonder what other ways there were of approaching the problem’. We see here that for Moore, working with poetry was about much more than producing narrative illustration.

Explore the poems and documents that inspired Henry Moore on our Myths & Poetry Tumblr