Picasso Through the Lens of David Douglas Duncan

3 February - 28 February 2020

Gstaad

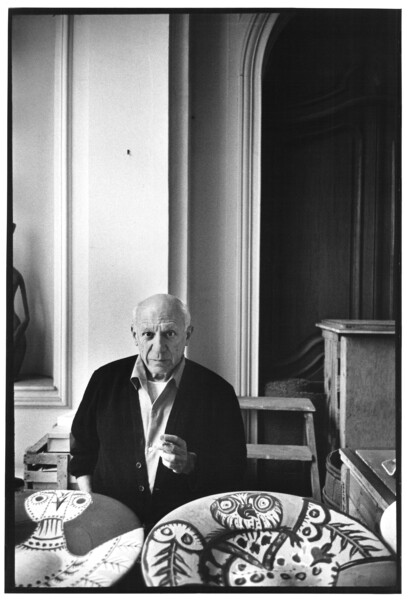

Opening at Vieux Chalet in Gstaad on the 2 February 2020, ‘Picasso Through the Lens of David Douglas Duncan’ gives a remarkable insight into the work and life of Picasso. Ceramics and paintings by the artist are presented in tandem with vintage photographs taken by the legendary photographer David Douglas Duncan during a period of unprecedented access to the artist’s studio. The works on view, created concurrently with the photographs, can be encountered as an ‘intervention’ throughout the domestic spaces of the chalet. The photographs, some of which have never been exhibited before, give an intimate portrait of the artist at work and at home. The project has been organised in close collaboration with the artist’s son, Claude Picasso, and James Koch, Executive Director at Hauser & Wirth.

David Douglas Duncan was a renowned war photographer, photojournalist, and a self-described nomad. He was among the most influential photographers of the last century, capturing World War II, the Vietnam War, and photo essays for Life magazine which enabled him to roam the world. The resulting images filled more than 25 books, including eight on Picasso. Duncan’s first encounter with Picasso happened in February 1956 when he infamously rang the doorbell of La Californie, Picasso’s home in Cannes. The artist’s wife, Jacqueline, led him upstairs and he met Picasso in his bathtub, who allowed Duncan to photograph him. From that starting point, the photographer developed a lasting friendship with Picasso over the course of 17 years during which time he captured an astounding visual archive of the artist’s life at La Californie.

Several of the works displayed feature bulls and bullfights, a topic of enduring fascination for Picasso. A series of aquatints are characterised by the artist’s rapid, spontaneous gestures as he assuredly rendered the poses and acrobatic movements of the torero and bull in saturated black pigment. Duncan would often shoot the artist watching the drama, heroism and violence of bullfights and, subsequently photographed Picasso as he captured the experience back in the studio. In many of the vintage photographs, Picasso himself is the subject and is an active participant in how he is presented. In others, the décor and plethora of objects – such as easels, brushes, books and papers strewn over surfaces – are the focus, all provide a fascinating record of the studio and reveal his working process. Duncan himself described Picasso’s home as ‘a forbidden, painter’s paradise’.

Throughout the interior spaces of the chalet Picasso’s ceramic works are on view, revealing the remarkable scope of his creative experimentation with a variety of techniques, forms, styles and chance, his frequent ally. In his hands, the smooth, swollen volumes of bowls and vases metamorphose into the outspread wings of an owl, a proud bull, faces or fauns laid down in bold, sensitive lines that fuse sculpture and painting. They became objects he would revisit throughout his lifetime, often keeping them private, like ‘members of his household’. By placing Duncan’s photographs – candidly showing Picasso painting, incising and considering his ceramic pieces – in dialogue with the subsequent works, the viewer is given a privileged insight into their genesis. The photographer deftly managed to capture and translate decisive moments, gestures or glances that would impact the work’s essence and finish.

Alongside the photographs and ceramics on view in Vieux Chalet, are two celebrated paintings ‘Femme au chignon et au chapeau Jaune’ (1962) and ‘Femme assise tenant un petit chat’ (2 May 1964). Both works focus on a beautiful woman, with long dark hair, large eyes and Grecian features, and are most likely a reference to Picasso’s wife, Jacqueline. Although Picasso never had her formally pose for him in his studio, her image dominated the artist’s pictures in the last decades of his life. These representations of his wife moved beyond celebrating her physique. Picasso was mesmerised by her personality and temperament; he wished to capture and translate this onto canvas, revealing their shared devotion. This is evident in the carefully observed details, such as her contemplative pose or the tender way she holds the cat, and their interactions are also reinforced in the accompanying photographs that show the couple’s life at La Californie.

Duncan took some 25,000 incisive images of Picasso explaining, ‘He never asked me to take a photograph. ‘You take pictures, I paint’, that was the division of labour. He didn’t pose for me, but he never refused a picture either, never said no.’ [1] Duncan’s lasting documentation of Picasso and his family and friends, taken over years, provides a true portrait complete with personal anecdotes and humorous scenes that he snapped with discretion and affection. We are given glimpses into the artist’s world, both at work in his studio and at play with his children. The freedom to explore a selection of works with these images, both in a domestic setting, heightens the intimacy this special project featuring arguably the most important artist of the 20th century.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/mar/20/david-douglas-duncan-picasso-photographs

Related Content

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10