Bharti Kher

A Wonderful Anarchy

28 September - 5 January 2020

Somerset

Selected images

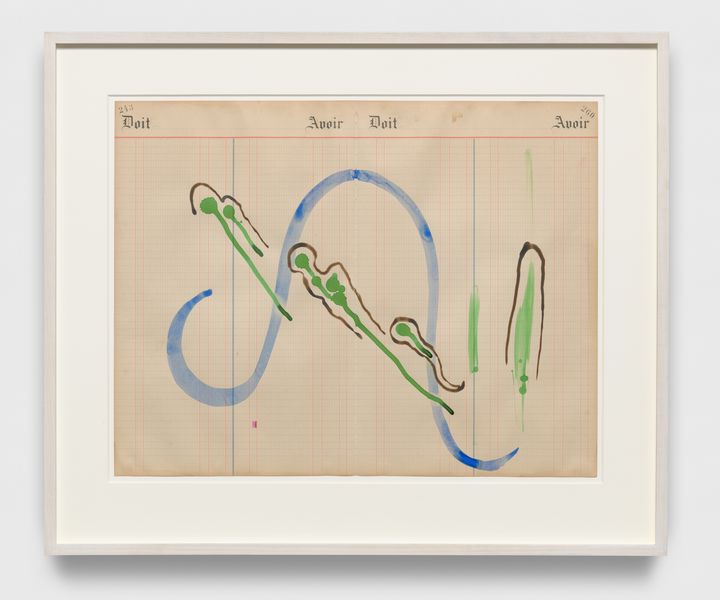

Sisters

2019

Installation views

1 / 6

Related Content

About the Artist

Bharti Kher

Born in London in 1969, Bharti Kher’s art gives form to quotidian life and its daily rituals in a way that reassesses and transforms their meaning to yield an air of magical realism. Now living between London, UK and New Delhi, India, her use of found objects is informed by her own position as an artist located between geographic and social milieus. Her way of working is exploratory: surveying, looking, collecting, and transforming, as she repositions the viewer’s relationship with the object and initiates a dialogue between metaphysical and material pursuits.

The bindi is an iconic personal affect of Indian women that is one of Kher’s signature materials and a loaded symbol. Since first appearing in her work in 1995, the bindi has inherited an aesthetic and cultural duality, a means to mix the superficial with the sublime. Kher explains: ‘Many people believe it’s a traditional symbol of marriage while others, in the West particularly, see it as a fashion accessory... But actually the bindi is meant to represent a third eye—one that forges a link between the real and the spiritual-conceptual worlds.’ Used as a material to articulate and animate her themes, bindis as such are not meant to be the central-motif of her work but rather act as a material, much like paint or clay, but with an inherent narrative. The bindis themselves undergo a shift in their initial cultural capital—they are defamiliarized, made to seem both scientific and mystical.

At the center of Kher’s practice are her sculptures, early examples of which featured fantastical hybrid characters, blurring the distinctions between humans and nature, ecology and politics. In line with this early practice, Kher continues to assemble, juxtapose and transform found objects that are witness to their own histories. Wooden wheels and architectural remnants, mannequin body casts and pillars all clash in mis-en-scenes of dystopia and grand orchestration. These elements are assembled in a hazardous manner; suspended from the ceiling, hanging from ropes, propped up and held from falling with the help of counterweights and balances; ultimately forming a heterogeneous narrative in which Kher further explores the artistic strategy of stripping objects of their meaning and making them open to misinterpretation and magic, creating alluring works of abstract beauty.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10