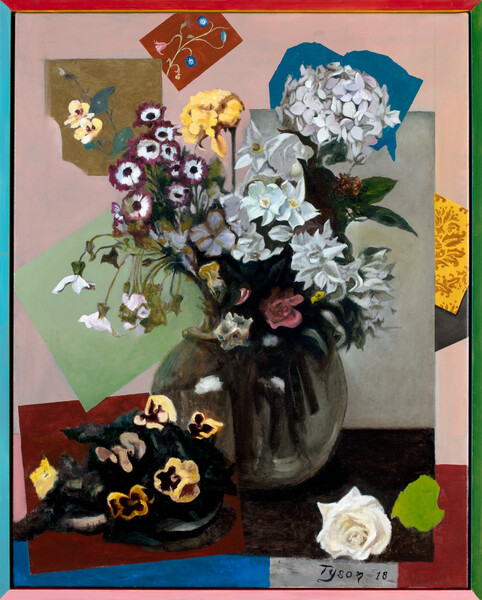

Hauser & Wirth London is proud to present ‘Life Still’, an exhibition of new paintings by Keith Tyson. The series of works displayed have a shared subject matter; they are all flower paintings. Through the prism of this singular genre, Tyson moves between the philosophical, the mathematical, and the mythological to create the 25 works in the exhibition. By taking a myriad of approaches, painting each canvas himself, Tyson draws on the information systems that surround and bombard us, reflecting an experience of the contemporary world we all inhabit. In this respect, beyond any reading of the subject matter, the content of the exhibition explores how painting is, and always has been, contingent on the conditions and context of its making. Tyson has referred to paint as a ‘programmable material’ and an ongoing interest in computers, coding and data has always been an important part of his life – from taking apart a motherboard as a teenager, to building ‘Art Machine’ early in his career. This featured algorithm generated combinations of words and ideas, which Tyson then realised in a multitude of media. His fascination with systems and the effect of data consumption manifests itself in the abundance of formal languages of painting in the exhibition. A celebration of the interconnectivity of the current age and its effect on himself and society is a counterpoint here to Tyson’s choice of subject matter which has a long-established art historical precedent. As Tyson says, ‘I don’t believe in a permanent self or in developing an artistic style. Our world is full of intricately connected systems and events. I’m simply trying to make work in collaboration with them.’The notion of the hybrid and a fertile cross-pollination of ideas runs as a theme throughout the exhibition. In a similar way that a florist would pick and combine flowers from disparate regions on a purely aesthetic basis, Tyson chooses assorted painting styles and associated references which in turn provide a conceptual framework to operate within. In some instances, the titles give a sense of the cultural coordinates which have emerged in the process of making the work. ‘Ikebana – Waterfall Stage (Boss Level)’ (2018) draws on a simultaneity of ideas, encompassing the formal Japanese flower arranging technique based on notions of idealised natural beauty and a blurred abstract background reminiscent of early modernist painting. Tyson collides source material to create a cosmology on the surface of the canvas, including a reference to a Chinese parable of enlightenment which appears in the tiny video game figures which populate the work. Throughout the exhibition, the artist’s interest in storytelling and mythology is matched by his enthusiasm for technology and the infinite possibilities it brings for cultural exploration. The laws of computer coding are mimicked in Tyson’s artworks through his take on a supposed rule of conceptual art; that there exists a parenthesis within which a conceptual artwork can be made. In this respect, the focus on one genre for the exhibition is a means of setting parameters or, as he explains, ‘limiting himself to one octave’. For Tyson, the intersection of the personal and subjective also plays a pivotal role in determining the outcome. Layered references are composed in each work like elements of a chord or symphony. A painting entitled ‘New Order (remix)’ (2018) is in part an homage to Peter Saville’s iconic design for the cover of New Order’s album ‘Power, Corruption and Lies’, an image with an emotional resonance from Tyson’s past. Here the paint-by-numbers strip on the edge of Saville’s design, itself suggestive of a language for machines or a colourful bar code, becomes a framing device which recalls Mondrian’s geometric abstraction. Further references skip between art historical eras; the theme of the collage appears both through the appropriation of flowers from different paintings by Henri Fantin-Latour and the forms of Henri Matisse’s late cut-out work, ‘The Snail’ (1953). In several instances it is the chance encounter or unpredictable occurrence that provides the starting point for the works. In the case of ‘These are the Greatest Times of our Lives’ (2019), the casual configuration of a candle, vase of flowers and empty vessel which Tyson encountered evolves into a Memento mori. Although the objects can be ‘read’ as symbolising the three stages of life, it is the formal properties of the painting which become its subject. Tyson gives the painting the appearance of a polaroid, a nod to the demise of the chemical photographic print, and its theme of obsolescence strikes a melancholic note. Tyson has often worked in series and here the cumulative impact of the repeated motifs — flowers, vase and support — draws attention to the different aesthetic styles in each painting. Like variations on a theme, the formal qualities of these individual works, become their subject with the potential to spark connections in the viewer’s mind. In this respect, the exhibition is both a philosophical and aesthetic meditation on the nature of painting itself and a celebration of the intricacies of contemporary life in the age of technology.