Fausto Melotti

The Deserted City

13 September - 27 October 2018

New York, 22nd Street

Selected images

Installation views

Related Content

About the Artist

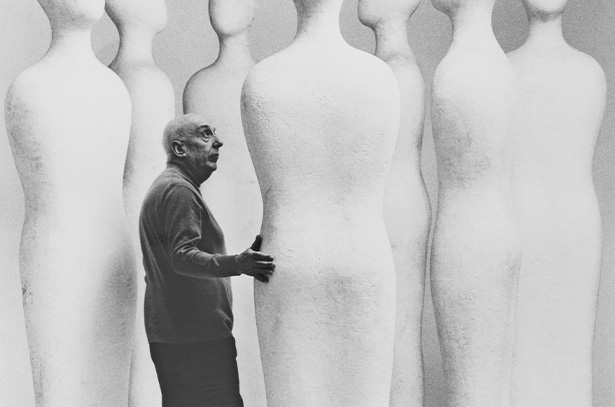

Fausto Melotti

Italian sculptor, painter and poet, Fausto Melotti is considered a pioneer of Italian art and is acknowledged for his unique contribution to the development of mid-century European Modernism. Coming of age in prewar Milan, and living through the horrors of the Second World War, Melotti metabolized wartime devastation in his work by returning to Renaissance principles of harmony, order, geometry, and musical structure, which he integrated into a highly personal yet universally accessible artistic language that expresses the full range of emotional experiences in modern human existence.

Before turning to art, Melotti studied music, mathematics and engineering—disciplines that exerted clear influence upon his distinctive practice across subsequent decades. Melotti trained as a figurative artist, studying under Italy’s leading Symbolist sculptor Adolfo Wildt at the Accademia di Brera in Milan. There he befriended fellow pupil Lucio Fontana in 1928, and in the following decade shifted his focus to abstraction and a new non-objective art. Melotti developed influential friendships with the Rationalist architects of Gruppo 7 and the abstract artists who gravitated around Galleria Il Milione. With Fontana, he joined the ‘Abstraction-Création’ movement, developing firm ideas about non-figurative art. Influenced by his education in engineering and music, Melotti’s first abstract sculptures were geometrical, and echoed the young artist’s academic training in order, rhythm, proportions and form.

Melotti’s ceramics of the 1940s respond to the pain, trauma, and despair that crowded his thoughts in the aftermath of the Second World War. Aerial bombings destroyed the artist’s studio in Milan and profoundly altered his artistic vision, precipitating a literal and symbolic rupture in his idealized pursuit of abstraction. His attention shifted to the craft and production of ceramics and terracotta. Rendered in polychromatic glazes, the enigmatic figures in these works illustrate the artist’s urgent and necessary return to figuration.

By the 1960s, Melotti had returned to sculpture, using a new language built upon delicate threads and thin sheets of brass, iron, and gold to express a more resolved and distinctly humanist sensibility. Delicately wrought, almost fragile constructions became enriched by a new narrative, dream-like and symbolic. These weightless works resemble aerial drawings incorporating space, air and transparency. His later work of the 1970s and 1980s is characterized by rhythmic geometric forms with an underlying humanist narrative that curator Douglas Fogle describes as ‘quivering just on the threshold between the solidity of figuration and the immateriality of abstraction.’

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10