Portable Art

A Project by Celia Forner

June 23 - August 12 2018

Los Angeles

Selected images

Related Content

About the Artists

Subodh Gupta

Subodh Gupta’s sculpture incorporates everyday objects that are ubiquitous throughout India, such as steel tiffin lunch boxes, thali pans, bicycles and milk pails. From such ordinary items the artist produces breathtaking sculptures that reflect on the economic transformation of his homeland. His works investigate the sustaining and even transformational power of the everyday.

Gupta has long explored the effects of cultural translation and dislocation through his work, demonstrating art’s ability to transcend cultural and economic boundaries. His ideas have taken shape in a variety of different media, from film, video and performance to steel, bronze, marble, and paint, which Gupta employs for both their aesthetic properties and as conceptual signifiers carrying a wealth of connotations. The mass-produced objects that have played such a prominent role in his art offer an ambiguous symbolism: while they are seen by those in the West as exotic and representative of Indian culture, to those in India they are common items that are used daily in almost every household, from the poorest to the most wealthy. Gupta harnesses these varying associations and, in the process, makes his materials subjects in their own right.

In recent years Gupta has shifted his attention from mass produced stainless steel objects to found objects. He is fascinated by the traces left on these objects by their previous owners, turning them from inanimate utensils into items charged with stories of lives lived, visualised by scratches and dents. Through them, viewers can detect what anthropologist and writer Bhrigupati Singh describes as ‘the patterns we create through our diurnal scrapings, the marks we leave night and day, through rise and fall, joy and sorrow, on the surfaces of our ordinary domestic vessels that journey with us, sometimes for years. What we discover in the process are intricately crafted pieces of the cosmos.’

Before his education as a visual artist, Gupta, who is passionate about film, was a street theater actor. The artist's change of residence from his native village to a major urban center is in a way an allegory of today's India. The growing middle class that migrated from villages to large cities is eagerly clearing the path for change and the dominance of global capitalist culture. Gupta is interested in what inevitably disappears in the process of such change.

Mary Heilmann

Influenced by 1960s counterculture, the free speech movement, and the surf ethos of her native California, Mary Heilmann ranks amongst the most influential abstract painters of her generation. Considered one of the preeminent contemporary Abstract painters, Heilmann’s practice overlays the analytical geometries of Minimalism with the spontaneous ethos of the Beat Generation, and are always distinguishable by their often unorthodox—always joyful—approach to color and form.

Raised in San Francisco and Los Angeles, Heilmann completed a degree in literature, before she studied ceramics at Berkeley. Only after moving to New York in 1968 did she begin to paint. While most artists at that time were experimenting with the concept of dematerialization and demanding that painting should avoid any references to experience outside the material presence of the work itself, Heilmann opted for painting, rebelling against the accepted rules. ‘Rather than following the decrees of modern, non-representational formalism, I started to understand that the essential decisions taken during the creative process were more and more related to content. The Modern movement was over…’

Since then, Heilmann has created compositions that evoke a variety of associations. Her work may be non-representational and based on an elementary, geometrical vocabulary—circles, squares, grids and stripes—but there is always something slightly eccentric, casual about them. The simplicity of the forms is played down by a deceptive form of nonchalance: the contours are not clearly defined. In some paintings, amorphous forms appear to melt into each other like liquid wax. Splashes of color can be discerned, sharp edges bleed for no apparent reason, and the ductus of the brushstrokes is always perceptible. Heilmann’s casual painting technique conceals a frequently complex structure that only gradually reveals itself to the viewer.

Bharti Kher

Born in London in 1969, Bharti Kher’s art gives form to quotidian life and its daily rituals in a way that reassesses and transforms their meaning to yield an air of magical realism. Now living between London, UK and New Delhi, India, her use of found objects is informed by her own position as an artist located between geographic and social milieus. Her way of working is exploratory: surveying, looking, collecting, and transforming, as she repositions the viewer’s relationship with the object and initiates a dialogue between metaphysical and material pursuits.

The bindi is an iconic personal affect of Indian women that is one of Kher’s signature materials and a loaded symbol. Since first appearing in her work in 1995, the bindi has inherited an aesthetic and cultural duality, a means to mix the superficial with the sublime. Kher explains: ‘Many people believe it’s a traditional symbol of marriage while others, in the West particularly, see it as a fashion accessory... But actually the bindi is meant to represent a third eye—one that forges a link between the real and the spiritual-conceptual worlds.’ Used as a material to articulate and animate her themes, bindis as such are not meant to be the central-motif of her work but rather act as a material, much like paint or clay, but with an inherent narrative. The bindis themselves undergo a shift in their initial cultural capital—they are defamiliarized, made to seem both scientific and mystical.

At the center of Kher’s practice are her sculptures, early examples of which featured fantastical hybrid characters, blurring the distinctions between humans and nature, ecology and politics. In line with this early practice, Kher continues to assemble, juxtapose and transform found objects that are witness to their own histories. Wooden wheels and architectural remnants, mannequin body casts and pillars all clash in mis-en-scenes of dystopia and grand orchestration. These elements are assembled in a hazardous manner; suspended from the ceiling, hanging from ropes, propped up and held from falling with the help of counterweights and balances; ultimately forming a heterogeneous narrative in which Kher further explores the artistic strategy of stripping objects of their meaning and making them open to misinterpretation and magic, creating alluring works of abstract beauty.

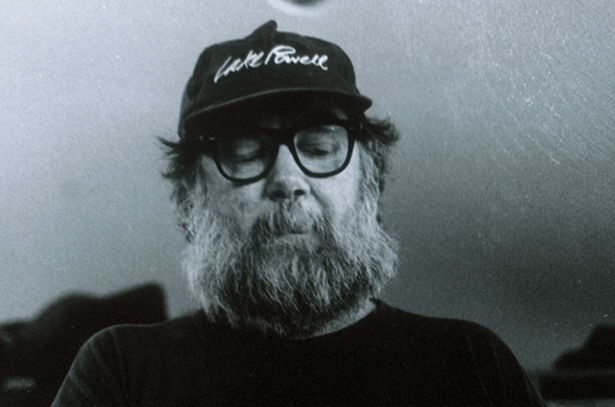

PAUL McCARTHY

Paul McCarthy is widely considered to be one of the most influential and groundbreaking contemporary American artists. Born in 1945, and raised in Salt Lake City, Utah, he first established a multi-faceted artistic practice, which sought to break the limitations of painting by using unorthodox materials such as bodily fluids and food. He has since become known for visceral, often hauntingly humorous work in a variety of mediums—from performance, photography, film and video, to sculpture, drawing and painting.

During the 1990s, he extended his practice into installations and stand-alone sculptural figures, utilizing a range of materials such as fiberglass, silicone, animatronics and inflatable vinyl. Playing on popular illusions and cultural myths, fantasy and reality collide in a delirious yet poignant exploration of the subconscious, in works that simultaneously challenge the viewer’s phenomenological expectations.

Whether absent or present, the human figure has been a constant in his work, either through the artist‘s own performances or the array of characters he creates to mix high and low culture, and provoke an analysis of our fundamental beliefs. These playfully oversized characters and objects critique the worlds from which they are drawn: Hollywood, politics, philosophy, science, art, literature, and television. McCarthy’s work, thus, locates the traumas lurking behind the stage set of the American Dream and identifies their counterparts in the art historical canon.

McCarthy earned a BFA in painting from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1969, and an MFA in multimedia, film and art from USC in 1973. For 18 years, he taught performance, video, installation, and art history in the New Genres Department at UCLA, where he influenced future generations of west coast artists and he has exhibited extensively worldwide. McCarthy’s work comprises collaborations with artist-friends such as Mike Kelley and Jason Rhoades, as well as his son Damon McCarthy.

Pipilotti Rist

Pipilotti Rist, a pioneer of spatial video art, was born 1962 in Grabs in the Swiss Rhine Valley on the Austrian Border and has been a central figure within the international art scene since the mid-1980s.

Astounding the art world with the energetic exorcistic statement of her now famous single channel videos, such as ‘I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much,’ 1986 and ‘Pickelporno,’ 1992, her artistic work has co-developed with technical advancements and in playful exploration of its new possibilities to propose footage resembling a collective brain. Through large video projections and digital manipulation, she has developed immersive installations that draw life from slow caressing showers of vivid color tones, like her works ‘Sip My Ocean,’ 1996 or ‘Worry Will Vanish,’ 2014.

For Rist, showing vulnerability is a sign of strength on which she draws for inspiration. With her curious and lavish recordings of nature (to which humans belong as an animal), and her investigative editing, Rist seeks to justify the privileged position we are born with, simply by being human. Her installations and exhibition concepts are expansive, finding within the mind, senses and body the possibility for endless discovery and poetical invention. ‘Pixel Forest,’ 2016, made from 3,000 thousand LEDs hung on strings, resembles a movie screen that has exploded into the room, allowing viewers an immersive walk through 3-dimensional video. As she herself puts it, ‘beside the energy-intensive exploration of the geographical world, pictures, films and sounds have been and are the spaces into which we can escape... The projector is the flamethrower, the space is the vortex and you are the pearl within.’

Since 1984, Rist has had countless solo and group exhibitions, and video screenings worldwide. Her recent solo exhibitions are 'Electric Idyll' at the Fire Station Doha (2024), 'Prickling Goosebumps & A Humming Horizon' at Hauser & Wirth New York and Luhring Augustine Chelsea (2023-24), 'Behind Your Eyelid' at Tai Kwun Hong Kong (2022), ‘Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor’ at The Geffen Contemporary, MOCA, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (2021 – 2022), ‘Your Eye Is My Island’ at MoMAK, The National Museum of Modern Art Kyoto and ART TOWER MITO (2021). ‘Åbn min Lysning. Open my Glade’ at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art Humlebæk Denmark (2019), ‘Sip My Ocean’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney (2017 – 2018), ‘Pixel Forest’ at New Museum New York (2016 – 2017) and ‘Your Saliva is My Diving Suit of the Ocean of Pain’ at Kunsthaus Zürich (2016), all resulted in record-breaking attendance numbers for each institution. A major exhibition is planned for summer 2025 at UCCA Beijing.

Phyllida Barlow

For almost 60 years, British artist Phyllida Barlow took inspiration from her surroundings to create imposing installations that can be at once menacing and playful. She created large-scale yet anti-monumental sculptures from inexpensive, low-grade materials such as cardboard, fabric, plywood, polystyrene, scrim, plaster and cement. These constructions were often painted in industrial or vibrant colors, the seams of their construction left at times visible, revealing the means of their making.

Barlow’s restless invented forms stretch the limits of mass, volume and height as they block, straddle and balance precariously. The audience is challenged into a new relationship with the sculptural object, the gallery environment and the world beyond.

‘There’s something about walking around sculpture that has the possibility of being reflective, like walking through a landscape,’ Barlow has said. ‘The largeness of sculpture has that infinite possibility to make one engage beyond just the object itself and into other realms of experience.’

Barlow exhibited extensively across institutions internationally and in 2017 represented Britain at the Venice Biennale.

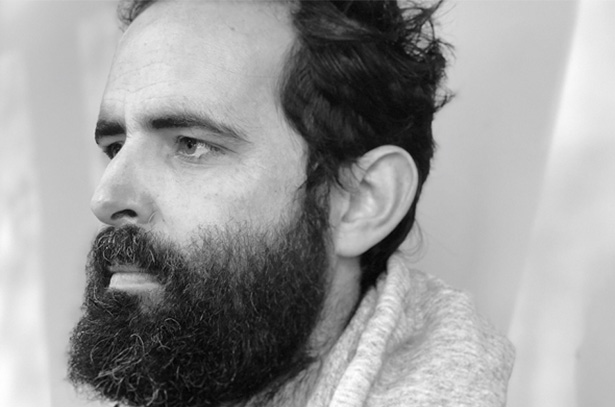

Stefan Brüggemann

Spanning—and sometimes combining—sculpture, video, painting, and drawing, Stefan Brüggemann’s work deploys text in conceptual installations rich with acerbic social critique and a post pop aesthetic. Born in Mexico City and working between Mexico, London and Ibiza, the artist’s oeuvre is characterized by an ironic conflation of Conceptualism and Minimalism. In this way, Brüggemann’s practice sits outside the canon of the conceptual artists practicing in the 1960s and 1970s, who sought dematerialisation and rejected the commercialisation of art. Instead his aesthetic is refined and luxurious, whilst maintaining a punk attitude.

The philosophy of language is a crucial tenet in Brüggemann’s practice, in which text functions as a fluid medium, utilized for both form and meaning; his choice of words typically provocative, acerbic and topical. Brüggemann’s masterful wordplay and conceptual rigour coalesce to create a bold and pertinent body of work focusing on themes of appropriation and displacement.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10