Books

New and Forthcoming Titles

A selection of new titles that we have enjoyed recently

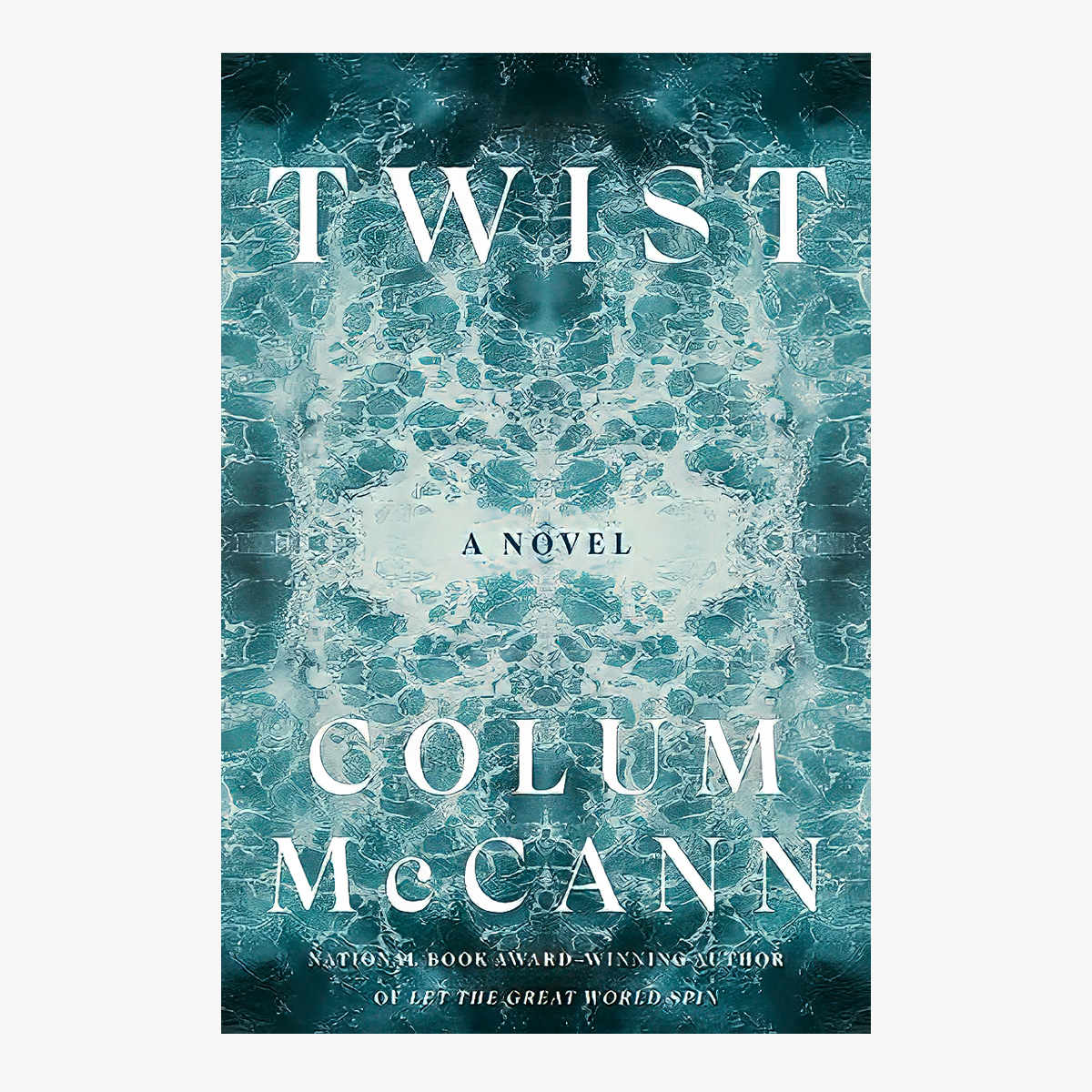

Twist

Colum McCann

(Random House)

Colum McCann has long been interested in the idea of convergence. His 2009 novel, Let the Great World Spin, follows eleven seemingly unrelated people in 1970s New York whose lives are intertwined in wondrous and tragic ways. His eighth novel, Twist, propels the idea of connection into a mesmerizing, present-day nautical tale. Anthony Fennell, a forty-eight-year-old Irish writer drifting into obscurity, accepts a journalistic assignment in Cape Town. A fiber-optic cable along the ocean floor has ruptured, leaving banks, hospitals, businesses and residents in West Africa without internet. Fennell joins the crew of a repair vessel to report on the mission and its mysterious leader, John Conway.

Fennell and Conway both battle the undertow of alcohol and family estrangement. Fennell’s narration charts the men’s physical and mental descent, as well as Fennell’s desire to repair himself. Conway, an obsessive freediver, boasts that his heart rate can drop to ten beats a minute underwater. McCann’s storytelling rhythm likewise shifts deftly from slow pulse to rapid pounding; in passages of unflinching honesty, he tells a story as meditative and harrowing as the ocean itself.

—Alexandra Vargo

Twist by Colum McCann. Courtesy Random House

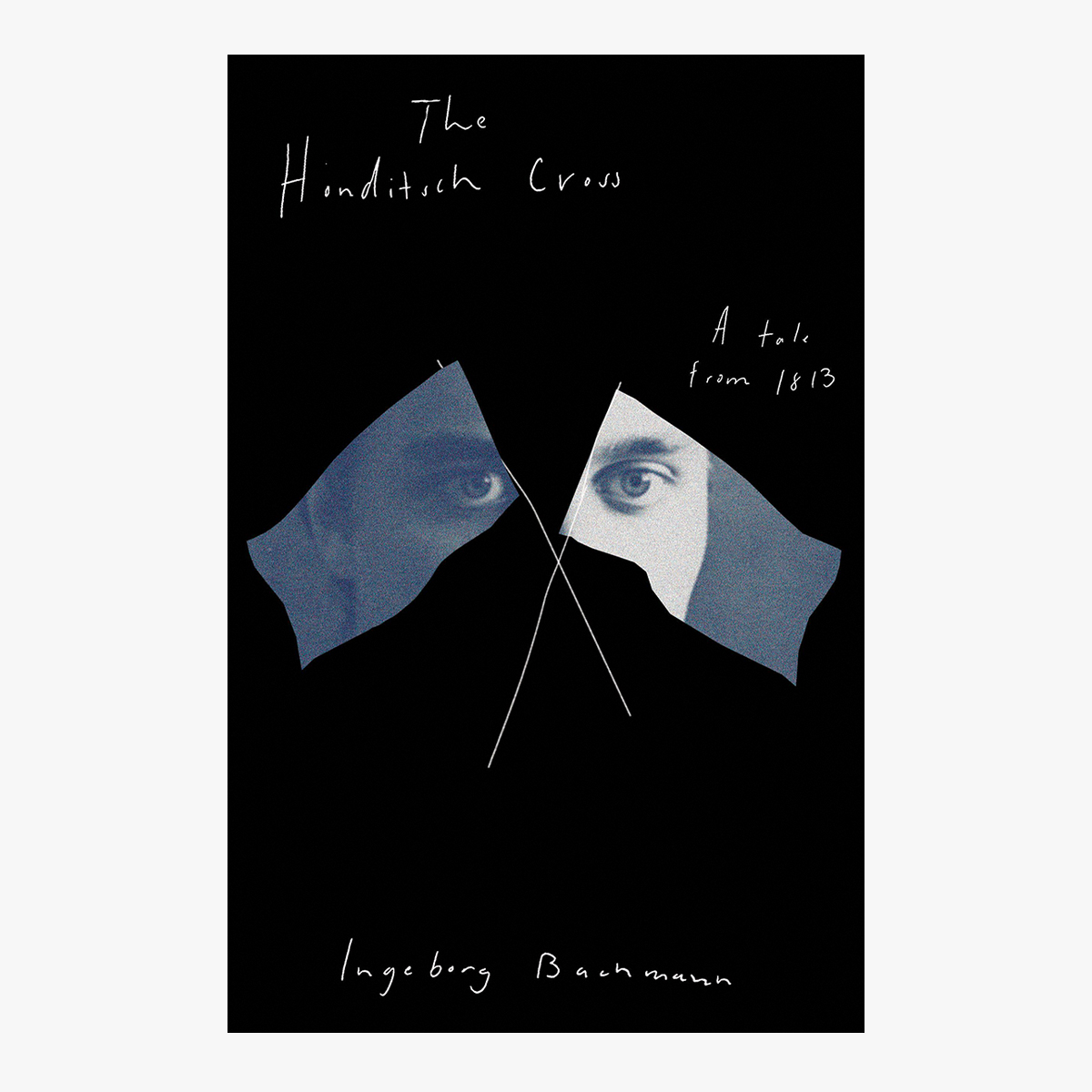

The Honditsch Cross by Ingeborg Bachmann. Courtesy New Directions

The Honditsch Cross

Ingeborg Bachmann

(New Directions)

On one of my shelves is a university library copy of Ingeborg Bachmann’s novel Malina (1971). When a friend and favorite poet of mine (her words are like hats to reach into for rabbits) told me it was her favorite, I found it in the stacks and never returned it. I fell in love with Bachmann’s use of language from the novel’s first lines (a “pathological agitation” with the word “today”), the way she lifted words from their utility and gave them a way out, a subtler body to “word” in. It’s the kind of writing that changes the way you want to read. When I saw that New Directions was publishing a translation of a novella she wrote when she was only eighteen, I was curious to read it, in part to understand the development of her writing and her mind. The Honditsch Cross, set in her native Austria in 1813, takes up the life of a young theology student facing war while “everything . . . shouted: life!” While the book’s linguistic approach is more immediate, my joy in reading it lay in recognizing the author, still: in her intelligence and patient intensity and her take on intimacy, resistance and the female experience within boundaryless war.

—Jana Horn

Six Sermons for Bob Dylan

Lucy Sante

(Tenement Press)

Lucy Sante has been one of my favorite writers ever since I picked up Low Life, her classic history of the New York demimonde, published in 1991, the year I moved to the city. Little did I know that in the ensuing years, as she was turning out other great books, Sante was also a secret copywriter for Bob Dylan, taking on assignments as varied as speeches, press kits and a Buick commercial. (A Buick commercial!) Then in 2016 she received a truly Dylanesque request: a series of sermons to accompany a film focused on Dylan’s gospel years, 1979 and 1980, during his brief conversion to born-again Christianity. Sante, no churchgoer she, gulped. But she signed on and we’re all sanctified as a result. Inspired by sermons recorded in Black churches in the 1920s and 1930s, Sante’s are soul poems for 21st-century uncertainty. On the topic of prudence, she evangelizes with holy sight: “… sometimes fools succeed. They go over the falls and come back alive. When that happens, we forget that they are fools and call them heroes.”

—Randy Kennedy

Six Sermons for Bob Dylan by Lucy Sante. Courtesy Tenement Press

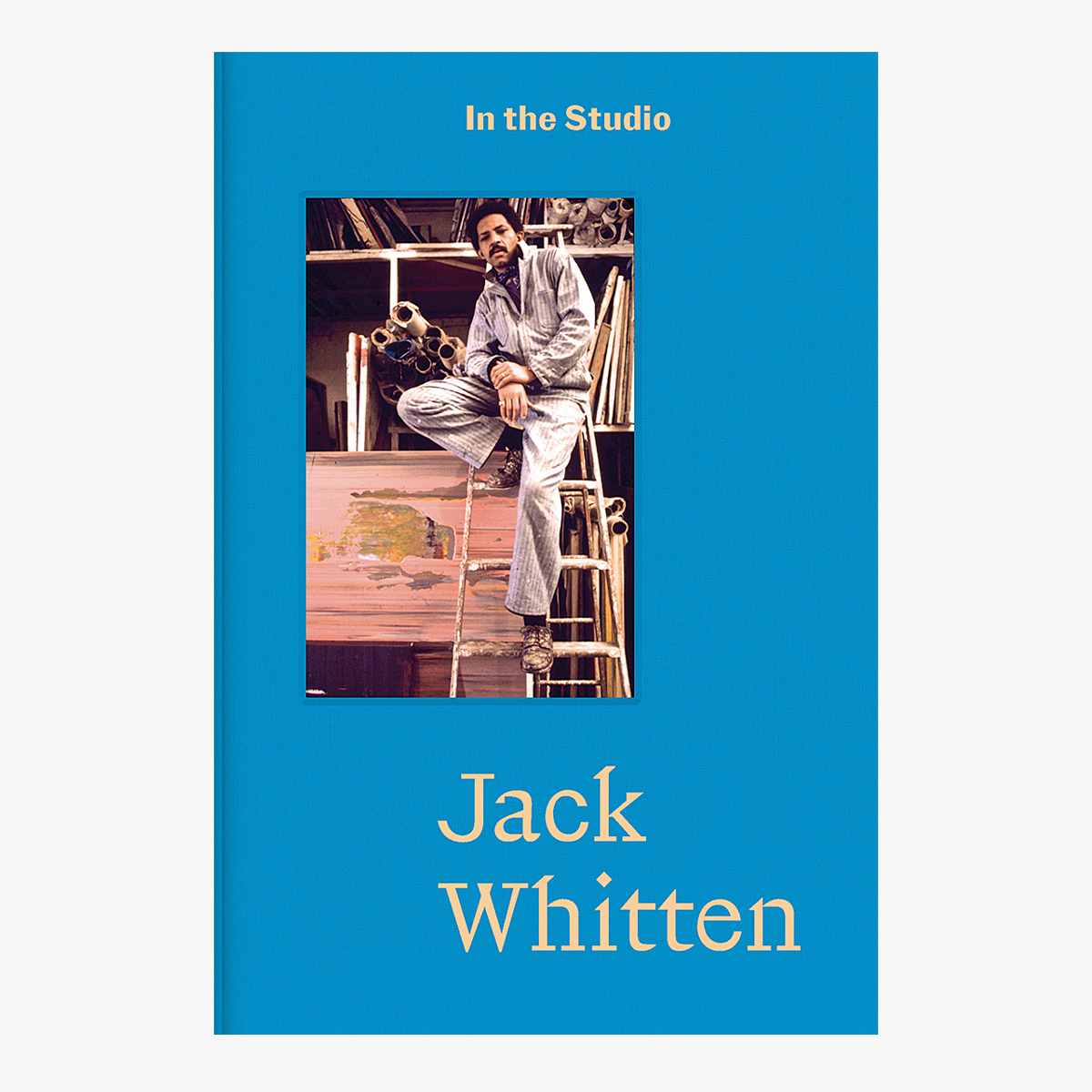

In The Studio: Jack Whitten. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Publishers

From Hauser & Wirth Publishers

In The Studio: Jack Whitten

More than an introduction to Jack Whitten, In the Studio takes us on a granular, subjective journey through six decades of his life and work. Yinka Elujoba’s essay—neither exclusively biographical nor exhibition-based, and accompanied by archival studio shots, installation views and portraits—cleverly informs and entertains, providing glimpses into the places Whitten studied, the people he met, the music he listened to and the convictions he formed about the act of painting.

“I just want a slab of paint,” the artist once said.

We come to understand him through the ways in which his studio life intertwined with his daily life—his navigation of macho abstract painting in the 1960s, his work in wood, the sculpture he made in Greece, his love of jazz and its influences on his thinking, from art to race, gender and survival itself.

—Debbie Hillyerd

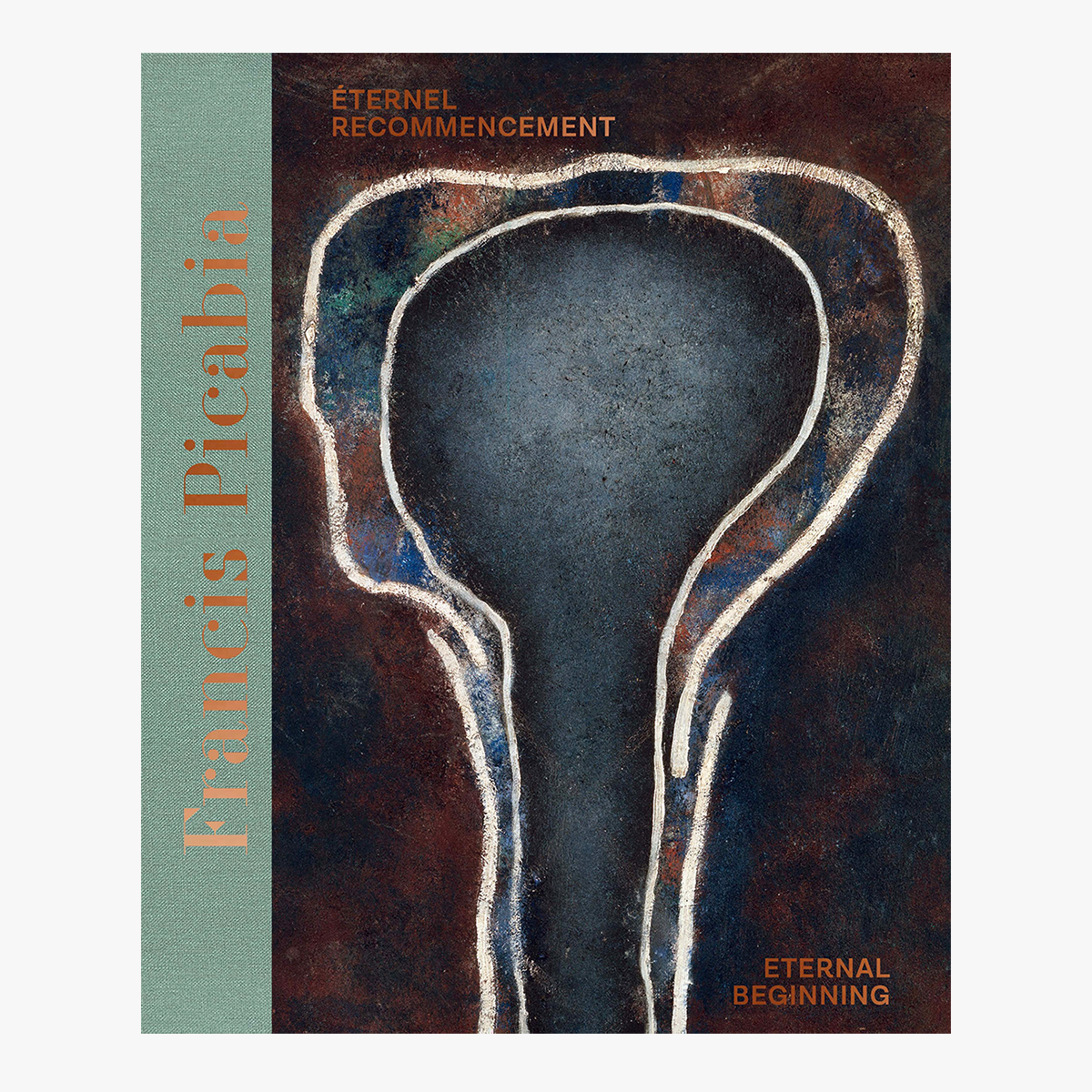

Francis Picabia: Éternel recommencement / Eternal Beginning. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Publishers

David Hammons. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Publishers

Francis Picabia: Éternel recommencement / Eternal Beginning

Francis Picabia was outlived by many of his fellow avant-gardists: Duchamp, Arp, Tzara and Picasso, whose lives stretched into the newly coherent art world of the 1960s. Picabia, by contrast and by virtue of being the first major modernist to pass away in the postwar fragmentation of the early 1950s, died before careful framing could situate his legacy. The effect was a strange disjuncture: Picabia’s late career, which lasted until shortly before his death in 1953, remained terra nova. This “Christopher Columbus of art”—as Arp termed Picabia—had arrived somewhere, but the where and what of this new world remained unclear.

Francis Picabia: Eternal Beginning, a timely survey of the artist’s late work and an accompaniment to two forthcoming exhibitions this spring, helps establish some coordinates. The book opens with a gorgeous facsimile of “Album Picabia,” Olga Mohler Picabia’s scrapbook turned artist’s archive, as well as new writing by Arnauld Pierre and Candace Clements. As if mirroring the “Album Picabia,” Pierre gives rich texture to the artistic milieu of the postwar period, placing Picabia in relation to Informel artists of the late 1940s. Clements goes further, offering a reading of the artist’s so-called repaints—a necessary and overdue intervention, and a model for paths into Picabia’s yet underexplored world.

—Jonathan Odden

David Hammons

David Hammons’s ascent to the pinnacle of the contemporary art world over the past three decades has coincided with his gradual absenting of himself from that world. “The less I do, the more of an artist I am,” he once said slyly. You might not guess this by looking at a shelf of books devoted to his work—more than twenty by my count and another thirty-some in which he plays a major role. But he’s had little involvement in many of these, and indeed some seem to have been published over his objections. This new volume, documenting his vast 2019 exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles, would be momentous if only for the fact that Hammons oversaw it. But it’s a real standout for another reason: Like the show itself, the book functions as a covert performance. During the exhibition’s run, Hammons unexpectedly spent considerable time in Los Angeles making subtle, ongoing changes to the look and feel of the galleries. This book plays conceptual adjunct to that evanescent presence, a show in its own right.

—Randy Kennedy