Conversations

Cases of the Reincarnation Type

A conversation with researchers at the University of Virginia’s Division of Perceptual Studies about normalizing the inquiry into extraordinary experiences

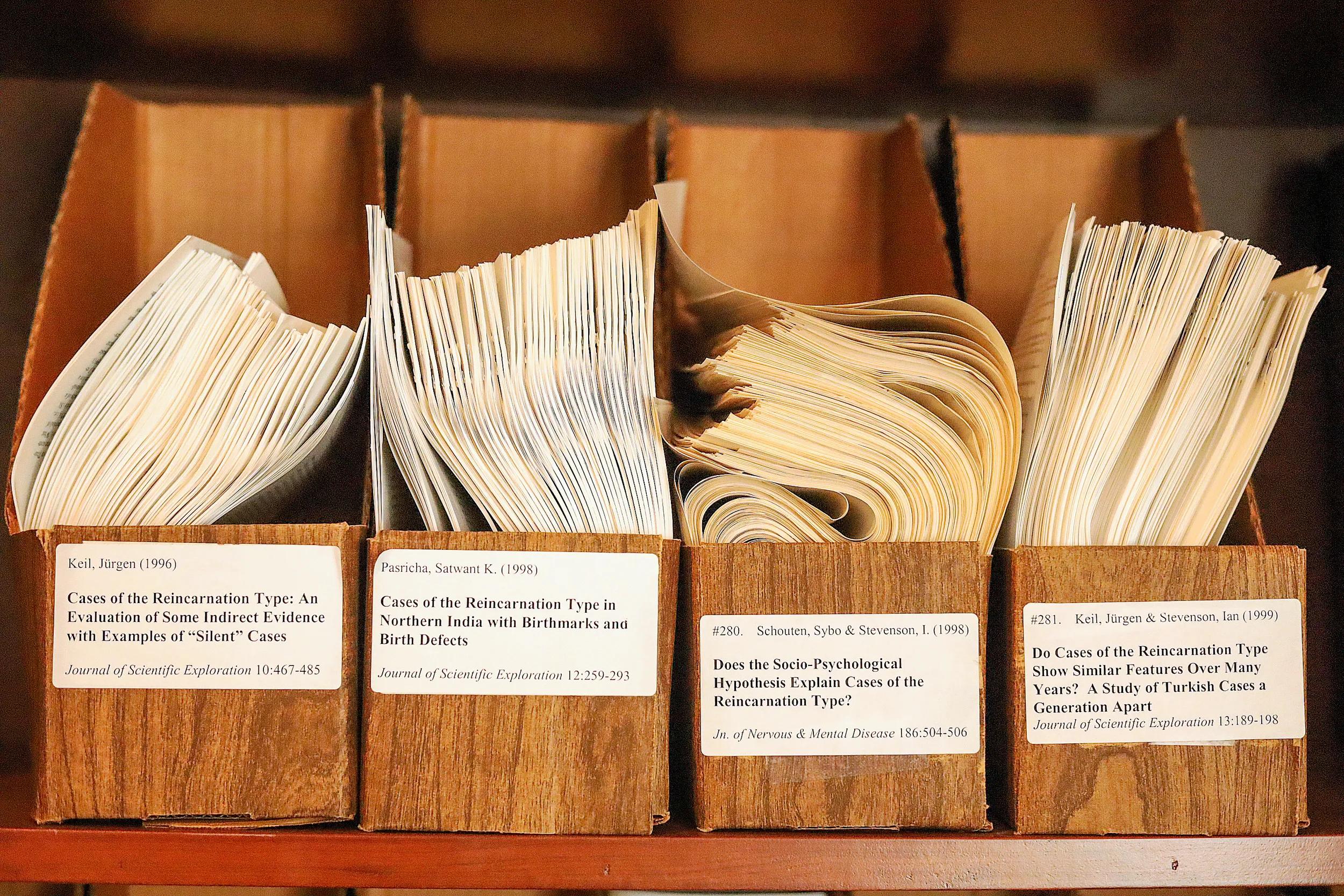

Selected published manuscripts displayed in the Ian Stevenson Memorial Library at the Division of Perceptual Studies (DOPS), University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. Photo: Kathryn Holstrom

In 2021, when I was in a graduate program for creative writing at the University of Virginia, I heard from a friend, who heard from a friend, about a professor who had access to a database—a “binder,” as this poet put it—of solved “cases of the reincarnation type.” Left with only this baffling crumb, I eventually reached out to the professor to ask if it was true. From there I was introduced to the Division of Perceptual Studies (DOPS), a department of the School of Medicine founded by psychiatrist Ian Stevenson in 1967 for the research of “survival phenomena”— evidence of life after death—which has broadened over time to include the study of fields such as mediumship, psychokinesis and remote viewing. This past fall, I sat down with Marieta Pehlivanova and Philip Cozzolino, two current members of the division, to talk about the particular focus of their research: children who report memories from previous lives.—Jana Horn

Jana Horn: What drew you to DOPS?

Marieta Pehlivanova: As a teenager, I was interested in the question of what happens after death. A few deaths happened around me, and I was reading books trying to make sense of it. It was comforting to read about how life continues, and maybe reincarnates, but on an intuitive level, it rang true. I had a deep recognition that there was something to it beyond the fact that it brought me comfort. Later, I was studying statistics, but still very interested in these topics—not only in pursuing them alongside academic studies but in actually applying my research skills to these phenomena. So I went to grad school for experimental psychology, because I thought that was one way to get into this work.

Philip Cozzolino: I think I was eight years old when the documentary Beyond and Back came out in 1978. I asked my mom to take me to see it. What eight-year-old says, “I want to see this documentary about near-death experiences”? Twenty years ago, I was fearful because I was a grad student doing this work, and I had a paper that I wanted to submit. It was around the time that I discovered the work of Bruce Greyson, my now-colleague here at DOPS, in medical journals. It gave me a sort of gravitas to say, “I can refer to near-death experiences now,” because there was a real scholar out there talking about these outcomes. I put out the paper, it was accepted by a mainstream journal, and my career began, of talking about near- death experiences and what we can learn from them. I did that for seventeen years at the University of Essex in England, in a mainstream psychology program. The end of this story is that one Friday I said, “I’m giving notice”—I would be unemployed for the first time in twenty-five years and had no idea what I was going to do—and the very next morning, a job opened up on LinkedIn at DOPS. It was just one of those moments where I’ve felt like something was more than coincidence.

“There are critical people out there, sure. There are people who are critical about what brand of bean you should eat, too. But there are also people with cognitive neuroscience training who are open to these ideas, or at least open to the idea of asking questions.” —Philip Cozzolino

MP: For most of us here at DOPS, it’s dream work. We’re led to this place through our own experiences, or being exposed to other people’s experiences, something that got us very curious, while also knowing the risk to our academic reputation.

JH: I was going to ask.

MP: I knew that once I touched this, I was not going to be able to go back to mainstream academia. I was OK with that.

PC: I left a tenured job, but for me it was, in some way, a perfect end to the cycle of what my career was. There are critical people out there, sure. There are people who are critical about what brand of bean you should eat, too. But there are also people with cognitive neuroscience training who are open to these ideas, or at least open to the idea of asking questions, because that’s what science should be, being open to asking questions.

JH: Do other programs like this exist?

MP: We try to collaborate as much as possible, but DOPS is unique, a division dedicated to studying “survival phenomena” within a public university in America.

JH: It’s amazing you’re on a college campus.

PC: The word we use here a lot is “normalize”—normalize the experiences, but also normalize the study of the experiences.

JH: What are you taking from the study of these experiences?

MP: The more compelling cases for me suggest there is something extraordinary going on that can’t be explained with our current understanding of how information is transferred in one’s mind. Whether that’s reincarnation or not is a whole other question. Even within the field of parapsychology, it’s a bit of a debate.

JH: If not reincarnation, it might just be some sort of—

MP: Anomalous access to the memories or consciousness of another person who lived, which is still fascinating.

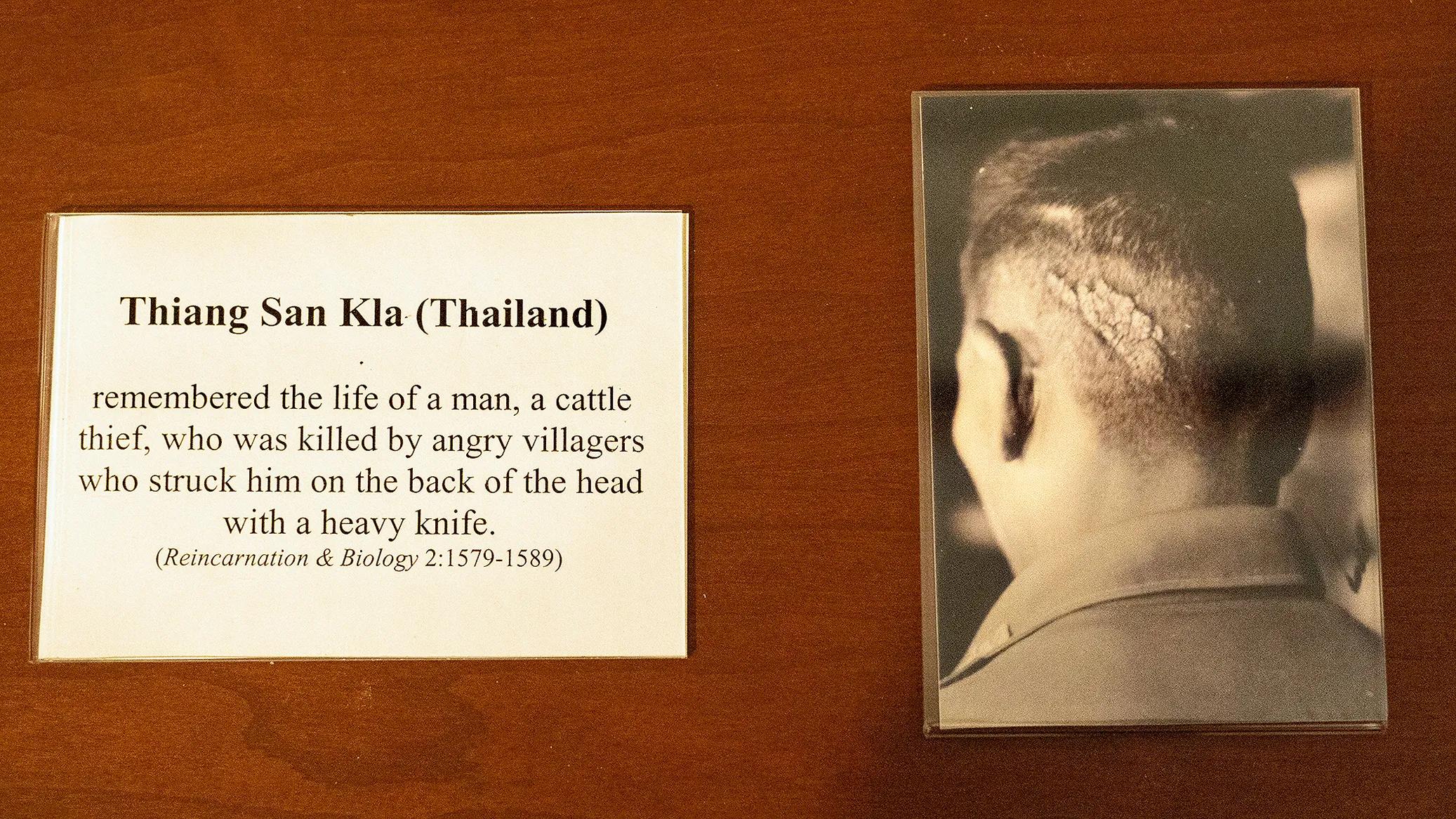

A case with a birthmark corresponding to the previous personality as documented in Reincarnation and Biology (Praeger, 1997). Photo: Kathryn Holstrom

JH: So fascinating. What would a “more compelling case” be?

MP: A famous case in America is James Leininger who, from a young age, was very interested in airplanes. When his dad took him to an aviation museum, he knew the names of the different types of fighter jets and specific terminology he hadn’t been exposed to. At the same time, he was having a lot of nightmares, which were very distressing to him and the family, in which he was seemingly reliving another person’s death by plane crash. He would then reenact the crash in his play. It was later determined by his statements that he was referring to James Huston, a World War II pilot who died in battle. This included matching the details of the friend who flew with Huston, because the child provided the name of that friend, Jack Larsen.

PC: He even named the boat that Huston was stationed on. His father asked, “What boat were you on?” The kid said, “Natoma.” The father said, “No, that’s a Japanese name,” and the kid said, “It was Natoma.” As it turns out, there was a boat named the USS Natoma Bay that Huston flew off of before he died.

JH: Wow. Is the evidence for these cases primarily statement-based?

MP: The statements themselves are not the evidence. It’s identifying the person who constitutes the evidence— a deceased person who closely matches the child’s statements, behaviors, birthmarks and phobias, if present.

PC: Statements matter, because they start the process, but there are other factors. I’m working on a paper looking at cases of a very rare phenomenon called xenoglossy, in which children speak a language they shouldn’t know. They’ve never been exposed to it, they don’t understand it, but they’re speaking it in some manner or form. There’s a select number of children whose xenoglossy links to the country they claim to have come from in a previous life. Just to give you a sense of what happens around here—I was gone for a few days last week, and in that time I got an email from a mother in New York saying, “My two-year-old is saying things in Russian, and I don’t understand why or how.”

“Historically, there’s been a barrier because our work gets censored. We've had success getting published, but we have to modify the language and make our findings ‘purported’ and ‘alleged.’ Hopefully one day we will not have to submit sanitized versions of manuscripts.” —Marieta Pehlivanova

JH: I’m just going to keep saying “wow.”

PC: And my xenoglossy paper hasn’t even been published yet! Whether it ends up being a legitimate case worthy of investigating or not, the prevalence of it just isn’t zero. Another “wow” feature are the birthmarks on some children.

MP: The biological birthmark evidence is compelling within the parapsychological community because if we assume the memories are real, meaning that they’re authentic—the child is authentically connecting to the memories of a person who once lived and died—the child could still have acquired these memories without having been the person. Maybe it’s not reincarnation, but it’s still extraordinary and anomalous that the child appears to have access to these memories.

JH: Right.

MP: But evidence like the birthmarks complicates that. It’s not just the memories, but a physical, direct connection to how this person died.

PC: Of the cases in which we’ve been able to identify a corresponding past personality, a birthmark relates to a fatal wound about twenty-nine percent of the time. These are cases that have been verified by medical records or by multiple people who knew the previous personality. It’s more like fifty percent if taken at face value, without available records to corroborate. Either way, it’s a huge part of the database.

JH: I was thinking, your data set is probably rather small, even if it’s large. Because, what are the odds a parent is going to take what their child is saying seriously enough to mention it to someone else, much less the Division of Perceptual Studies at UVA, which most people, even students at UVA, don’t know about?

PC: Exactly. We have 2,254 documented cases, and there is no question that that is an undercount. It could be massively undercounting how many children out there we could have studied.

MP: Just to give you some statistics, on average we hear from about 120 to 150 families a year. These are just the people who find us.

JH: Have you thought about going out there and recruiting?

MP: We will be.

“Just to give you a sense of what happens around here—I was gone for a few days last week, and in that time I got an email from a mother in New York saying, ‘My two-year-old is saying things in Russian, and I don’t understand why or how.’” —Philip Cozzolino

PC: We’re in the middle of studying a 1,000-person representative sample with which we’re trying to estimate: What is the actual prevalence of this? If you have a kid between certain ages in America, what is the likelihood that they are one of these kids? I think it’s a question we need to actually try to answer. There was a long Washington Post story on CORT [Cases of the Reincarnation Type] which documented some cases, including a young girl who talked about a numbered tattoo on her arm and how she died in a cloud of blue gas. Her mother was like, “How could she know about the Holocaust?” But what was interesting was the comments, about 5,000. All of these people saying, “Oh my God, I had no idea that people studied this....” Then they’d say: “When I was a kid....” or “When my kid was....”

MP: That study will be super exciting, depending on what we find. If it’s a non-trivial percentage, I think it will help advance this work and, again, normalize it. Historically, there’s been a barrier because our work gets censored. We’ve had success getting published, but we have to modify the language and make our findings “purported” and “alleged.” Hopefully one day we will not have to submit sanitized versions of manuscripts.

JH: I do think that there’s been a rise in curiosity about these things that could reach the mainstream.

PC: It just seems like people are getting to a point at which materialistic science is no longer satisfying, because their lived experience is different. We sometimes refer to these things as anomalous, but more and more research shows it’s not anomalous at all. People have out-of-body experiences. They have near-death and psychedelic and mystical experiences. I mean, it’s happening.

MP: The “anomalous” thing is another example of how we’ve had to sanitize the language.

JH: By saying that it’s more random, or rare, than it really is?

MP: Yes. If you poll people on a range of these experiences, the vast majority have had at least one of them. In that sense, it’s normal. It’s anomalous not to have had an experience. I do think we’re riding a wave of people becoming more open.

PC: I agree. There are physicists out there talking about theories of many universes, and time-space issues that map consciousness as its own entity and not just a byproduct of flesh. I see that as part of the wave.

Utensils manipulated by DOPS research subjects and faculty purportedly using psychokinesis—the mind’s influence over matter. Photo: Kathryn Holstrom

JH: Is there something in the database that personally motivates you? A question that you’re hoping to answer?

MP: Something that excites me is the idea that we could look at certain phenomena—such as gender nonconformity, on which a lot of research has been done—to see if past- life memories could have something to do with it. If there’s a unique factor that’s neither genetic, as far as we understand, nor environmental, that could be contributing to some behaviors.

PC: Or prodigious talent. One of the approaches we’re taking is not just looking in our database to see if a child has a skill but actually going out and finding people with great talent who were prodigious as children and asking the parents, “Did they ever say things like this?” Because it’s just a kid, and most people don’t know about our work. What if some non-zero percent of prodigies were trying to express past-life memories?

JH: That kind of answers my next question. Why don’t I remember my past life? I must not be particularly talented!

MP: That’s a big question of ours, too. If reincarnation is real, do we all reincarnate? Is it just some kids? Or is it just that some kids happen to remember?

PC: If reincarnation is real . . . let’s just play the game. Maybe these kids are a glitch in the system. These things are probably not supposed to be remembered. “Supposed to” sounds like there’s a plan, but I guess I’m just saying that you probably don’t want to be a four-year-old talking about when you died in that fire.

MP: Or to feel disconnected from your family.

PC: And maybe the glitch has to do with the trauma, the emotion, that somehow mucks up the process. I don’t know. It’s fun to speculate about.

JH: Are you ever dealing with parents who are a bit . . . excited?

PC: We’re very attuned to that. I have a paper under review right now that looks at parental attitudes and whether they are encouraging or suppressing—suppressing to the point of physical punishment, slapping a child, saying, “Stop doing this.” You would think that the greater the strength of the case, the better the story and book they’re going to sell. But one of the big findings from that study is that the stronger the case, the more likely parents were to suppress the child’s statements.

JH: Parents don’t want their kids saying they’re not their parents.

PC: No, it freaks them out. It’s fun to have these conversations, but at the end of the day, these are parents with children who are, in many cases, in a very challenging situation, with other kids, and jobs, thinking, “What am I supposed to do?” The phenomenon is real. What’s behind it, we don’t know. But it is qualitatively different from other experiences that children have. We have to remember that, amidst all the sexy stuff about reincarnation.

MP: It’s important for us to put some studies out there that specifically talk about the experience of parents, to raise awareness that this is a normal childhood experience that in most cases doesn’t seem to be affecting people very deeply. Kids tend to grow out of it. The more we can normalize this, the better it’s going to be for the kids, for the parents and also for the research.

–

Philip J. Cozzolino is an associate professor of research in the Division of Perceptual Studies at the UVA School of Medicine. Inspired by research into near-death experiences, he generated a psychological model linking healthy considerations of death to increased well-being, self-direction and authenticity. He currently investigates children’s reports of past-life memories.

Marieta Pehlivanova is a research assistant professor of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences at UVA. Her research focuses on near-death experiences and children who report past-life memories. She is particularly interested in understanding the factors contributing to the emergence of these phenomena and exploring ways to support individuals who experience them.