Essays

Cross Gender / Cross Genre

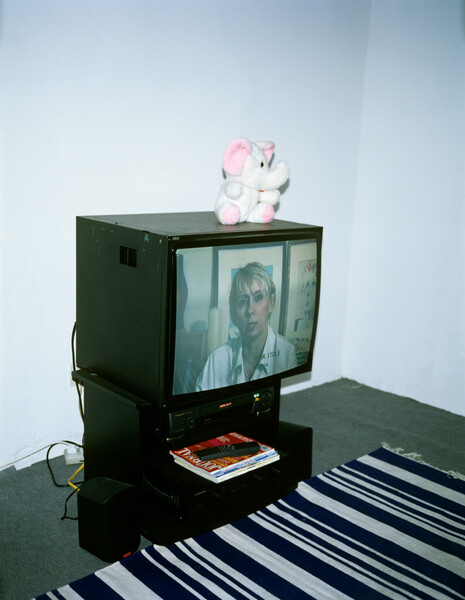

Mike Kelley, Unisex Love Nest, 1999. Installation view, Hauser & Wirth, Frieze Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 15 - 17 February 2019. © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

- 10 February 2019

'Cross Gender / Cross Genre' as later published in 'Foul Perfection: Essays and Criticism' by Mike Kelley, edited by John C. Welchman, Cambridge/MA: MIT Press, 2003. Frieze Los Angeles 14 – 17 February 2019

- Related Artist

- Mike Kelley

Mike Kelley’s seminal installation ‘Unisex Love Nest’ (1999), was first conceived at the Palais Attems in Graz, Austria. Inspired by a photograph of an idealized child’s bedroom that Kelley found in the magazine ‘First for Women’, the installation examines pop psychology and repressed memory through an array of cultural references. Within ‘Unisex Love Nest’ a television set plays the video work ‘Cross Gender / Cross Genre’. Watch excerpts and read Kelley’s essay of the same title below, prefaced by his original introduction.

Cross Gender / Cross Genre Mike Kelley, 1999

This paper was originally presented on September 26, 1999, in Graz, Austria, at the Steirischer Herbst festival as part of 'Re-Make/Re-Model: Secret Histories of Art, Pop, Life, and the Avant-garde'—a series of panel discussions sponsored by the Berlin Group and the Steirischer Herbst focusing on the politics of queer aesthetics. I also mounted a video installation at the Palais Attems titled 'Unisex Love Nest,' which included a feature-length videotape compilation composed of selections of period cross-gender-related films and documentation, as well as contemporary interviews with some of the artists.

My intention here is to present some thoughts on the aesthetics of the period from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s in relation to images of gender confusion. This decade, which, for want of a better term, I call the ‘psychedelic’ period, is rife with such images. I will attempt to explain why I believe this is so, and to describe some of the avant-garde clusters and pop genealogies associated with this cross-gender phenomenon. It’s best to begin by explaining where I come from and thus why this theme is important to me. Born in 1954, I came of age at the tail end of the 1960s, a period of immense social change and unrest in America. I was fourteen in 1968, conscious enough to feel a part of the general social turmoil, too young to be a real hippie, but just old enough to be eligible for the Vietnam draft. However, my worldview was very much a by-product of the countercultural movement.

As a result, I had nothing in common with my older siblings. They were ‘postwar’; I was part of the TV generation. I was mediated . . . I was ‘Pop.’ I didn’t feel connected in any way to my family, to my country, or to reality for that matter: the world seemed to me a media facade, and all history a fiction—a pack of lies. I was experiencing, I think, what has come to be known as the postmodern condition, a form of alienation quite different from postwar existentialism because it lacks any historical sense—there is no notion of a truth that has been lost. It is characterized by the feeling that there is a general evenness of meaning. To borrow a phrase from Richard Hell, I was part of the ‘blank generation.’[1]

Mike Kelley, Unisex Love Nest, 1999. Installation view, Steirischer Herbst 99, Palais Attems, Graz, Austria, 1999 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY

Mike Kelley, Unisex Love Nest, 1999. Installation view, Steirischer Herbst 99, Palais Attems, Graz, Austria, 1999 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY

I was, however, sufficiently caught up in the ‘60s ethos to involve myself in radical politics, at least as a spectator. In Detroit, Michigan, the city where I grew up, the local version was the White Panther Party [2]—supposedly a white spin-off of the revolutionary Black Panther Party. In reality it had more in common with the Yippies,[3] the mostly white, hedonist, anarchist group whose politics consisted primarily of ‘acting out’—making one’s life into a kind of radical street theater. The purpose of this exercise was to render oneself unfit to function in normal society, and thus to prevent oneself from participating in and prolonging it. As the logic went, if one consumed enough drugs, one simply could not work in the military-industrial complex.[4] White Panther activity was centered in the college town of Ann Arbor, and my interest in it drew me to related avant-garde music, theater, film, and political events. This is what led me to become an artist, which is quite remarkable, since I come from a working-class background and had little or no exposure to the fine arts as a child.

When I first heard Psychedelic music it was as if I had discovered myself.

This psychedelic culture [5] completely altered my worldview. When I first heard psychedelic music,[6] it was as if I had discovered myself. I had never cared much for music before I heard bands like the MC5, the Stooges, the Mothers of Invention, and Jimi Hendrix. Their fractured music made sense to me— it mirrored the nature of the world as I understood it, and that of my own psyche. Of course, as every educated person knows, this was all old hat in relation to modernism—the avant-gardes at the beginning of the century: cubism, futurism, dada, and surrealism. But I was encountering a phenomenon of mass culture, not high art. One of the most interesting things about the late ‘60s is that the historical avant-gardes were picked up and inserted into popular culture under the guise of radical youth culture. In one swoop, surrealism became teenybopper culture. This was possible because the artists working in this crossover period still considered themselves avant-garde, a notion still conceivable in those years. ‘Progressive’ psychedelic music emerged, formally, in concert with notions of progressive social change, a liaison that, while it quickly fell apart (as evidenced in the irony of the camp aesthetic),[7] was still operable at that moment. There are several strains within this progressive aesthetic, almost all sharing a link to the notion of the feminine.

The popular appeal of ‘60s radical youth culture in America was very much a by-product of the anti-Vietnam War movement. For the first time, complacent white youths were delivered into political consciousness by the threat of military conscription. The model for social protest was the black civil rights movement; the pacifist tendencies of Martin Luther King worked well with an antiwar message. It was this coincidental encounter between two very different constituencies that provoked, I believe, white male youths’ profound empathic connection to “otherness” in general. But the greatest ‘other’ was woman. If America’s problems were the result of being militaristic and patriarchal, the antidote would be the embrace of the prototypically feminine.[8] And contemporary radical culture was dominated by displays of femininity (pacifism, long hair, flowery clothes) presented as signs of resistance.[9] But not only femininity, male homosexuality as well, for the two were conflated in the popular mind.[10] If the female is other, then the homosexual is doubly other since he was supposed by straight culture to be ‘unnatural.’ In a sense, the Vietnam War itself promoted this posture, since one way to escape the draft was to play gay, a masquerade that may be one motivating factor for the coming decade of popular homosexual posturing that finds its apex in glam rock.[11]

If America's problem was that it was militaristic, patriarchal and male, then the antidote would be the embrace of the prototypically feminine.

Hippie and flower child cultures are the ‘natural’ versions of this dyad of the feminine and the homosexual, and camp is its unnatural cousin. Despite the fact that they are both generally ‘progressive’ and ‘leftist’ and share many surface similarities, they are aesthetically opposed. Jack Smith, godfather of the New York ‘60s avant-garde theater and film scene, exemplifies the difference.[12] Smith was a major influence on diverse New York trends (he was important, amazingly enough, to both the minimalist and maximalist camps); Warhol’s narrative films and the theater of Robert Wilson would almost be inconceivable without him, as would the junk sensibility of the East Village aesthetic.

Yet Smith achieved his greatest notoriety by making the first avant-garde transvestite film, Flaming Creatures (1962–63)—a kind of structuralist parody of Orientalist Hollywood films of the 1940s. Smith’s embrace of the phoniness of these films is central to the camp aesthetic—and its politics. The camp aesthetic itself is suspect, for you are never sure whether its joys are real or ironic. It is an arcane aesthetic. Like Smith, hippie culture also embraced non-Western cultures, mixing them together in a psychedelic stew. But the hippie aesthetic invested in a ‘truth’ located in the ‘other,’ who becomes our savior. While there is little room for irony in this essentialist position, it too is suspect, for the other in hippie culture is generally presented through exotic clichés—media-derived stereotypes of the Native American, the Indian mystic, and so on. The hippie aesthetic now seems kitsch, even if that was not the intention. Hippie has become camp by default.

Reference material. ‘Quick tricks for... A room to remember’ in: ‘First for Women,’ New Jersey, 13 September 1999 pp. 98 – 99, ill. Photo: Bruce McCandless. Courtesy of the Goetz Collection, Munich.

The primary signifier of psychedelic culture, the pastiche aesthetic, promotes confusion while at the same time postulating equality—all its chaotic parts are considered equal. This effect can be understood as either very democratic or profoundly nihilistic. We could describe the difference as set between a ‘utopian’ and a ‘black’ version of camp. The Cockettes—and the films of Steven Arnold—illustrate this difference.[13] The Cockettes were a San Francisco-based troupe that produced a kind of campy and parodistic transvestite theater that, unlike traditional transvestite shows, reveled in the exhibition of the incomplete pose.

Though they wore extravagant costumes that mimicked 1930s Hollywood notions of glamour, their feminine masquerade was deliberately provisional and half-accomplished. The ‘queens’ often had beards—a definite no-no in transvestite acts where ‘passing‘ as a woman is the sign of quality.[14] The Cockettes included women, yet these did not usually cross-dress as men. The aesthetic of the group was organized around a redefinition of glamour—an ‘alien’ glamour, if you will, but one still rooted in a feminine pose. Such was the group’s debt to hippie culture: they represent a true crossover between hippie communalism and a later, more overtly defined, ‘queer’ aesthetic. In the films of John Waters, by contrast, while no vestige of hippie remains, there is a similar play with gender slippage in the figure of the grotesque ‘drag queen’ Divine, who could never be mistaken for a woman.[15]

Waters celebrates ‘queerness’ for its abject nature relative to dominant American society. One need not search for an outside aesthetic in his films, because ‘you,’ the supposedly empathic film viewer, already represent the other.[16] The negative connotations of being ‘artistic’[17]—that is, pathological—are presented in Waters’s films in a completely unsublimated manner. The freakish characters in his films were not designed just to be laughed at; they are, in a sense, role models. His are low comedies with no ascendant intentions and no redeeming social value—they are post avant-garde and proto-punk. The Mothers of Invention have an abject aesthetic similar in some ways to Waters’s, but more traditionally avant-garde. The Mothers were a rock band formed in the mid-1960s by white R&B musician Frank Zappa,[18] who combined dissonance with his R&B roots under the influence of new music composer Edgard Varèse.[19]

The Mothers’ music exemplifies the psychedelic aesthetic in its use of pastiche structures, combining elements of pop, rock, free jazz, new music, electronic music, and comedy. The effect is akin to a live reenactment of a tape collage work by John Cage. The band was also overtly theatrical, adopting transgressive stage techniques (such as audience baiting and performative discontinuity)[20] derived from such modernist, post-Brechtian forms as the Happening. Their visual aesthetic was neodada: abject, ‘junk,’ and ugly. The Mothers were part of a larger community of musicians and artists in the Los Angeles area, centered primarily around Zappa, called the Freak Scene, which openly positioned itself against the hippie aesthetic of the natural.[21] This scene included the avant-garde rock groups Captain Beefheart, Alice Cooper, and the GTOs, the latter an all-female band composed of groupies.[22] All of these acts employed drag elements from time to time.[23]

As with the Cockettes, the Mothers’ version of drag was incomplete. But there are differences, for, despite their ridiculous image, the Cockettes had a playful, positive quality absent from the Mothers—whose use of drag has more in common with the traditional comedic adoption of female garb by the male, an is in that sense an abject usage. In Western culture, men who dress in female clothes are considered funny, while the opposite is generally not the case: a woman dressed in male clothes has little comedic value. The sexism underlying this difference is obvious, for why else should the adoption of feminine characteristics by a man be abject?[24]

This is not to deny that the Mothers were a politically conscious band—in fact, they were one of the most politically aware musical groups of the period. In a sense, though, they were a realist band ridiculing the romantic utopianism and exoticism of hippie psychedelia. Their satiric ugliness was meant to be a distorted mirroring of the values of dominant culture. The Alice Cooper band is somewhat similar, but more pop: their aesthetic is more flat and their intentions are less clear.[25] Like Zappa’s, early Alice Cooper records mix rock and roll with noise elements influenced by avant-garde music. Both share that anti-hippie reveling in the aesthetics of the ugly, though for Alice Cooper it’s a blend of transvestism and cheap horror-film theatrics. Their ‘decadent’ mixture of horrific and homosexual signification was designed for a much more general audience than Zappa’s.

Like Waters, they were unapologetic in their embrace of the low. It could be said that they were the first truly popular camp band—with two separate audiences. Alice Cooper was a very commercially successful pop band, putting out a string of top ten hits including ironic saccharine ballads that some of their audience read as parodies, while others embraced them as genuinely emotional.[26] Similarly, one part of their audience empathized with their freakish, decadent personas, while another simply perceived such roles as comedic. By virtue of their use of camp strategies, Alice Cooper could be said to have ‘outed’ the spectacular aspects of pop music. Pop music in America has long embraced the ‘glamorous,’ a.k.a. the homosexual, in closeted terms. Liberace’s campy stage act was never discussed openly in relation to his homosexuality. The performer himself foreclosed such considerations, once winning a lawsuit against a British gossip columnist who merely intimated that he was a homosexual.[27]

Somewhat ironically, considering the purported ‘sexual’ nature of the musical form, such sublimation pervades the history of rock and roll. Elvis’s appearance was repellent at first to his primarily country music audience because of his use of makeup;[28] but as he became more and more of a popular figure, this aspect of his stage act became invisible—naturalized. The so-called British invasion bands of the mid-1960s, like the Rolling Stones, picked up on this ‘glamorous’ posturing, filtering it through English visual tropes of foppish ‘decadence.’[29] Mick Jagger’s stage movements were at once ‘black’ and ‘gay,’ which made him twice evil—and doubly sexualized—in the eyes of his teenybopper fans. Such posing signals a major change in the pop arena, for its open flirtation with ‘evil’ is something that Elvis, with his desire to be a mainstream pop star, could never have entertained. It was only within the framework of the ‘60s counterculture that such a ‘transgressive’ aesthetic could find acceptance as ‘popular’ music.

From Jagger on, a whole string of figures raise the stakes in decadence and danger. The two most important are probably Jim Morrison of the Doors[30] and Iggy Pop of the Stooges.[31] Morrison is rumored to have lifted his leather boy look from the rough trade posturings of the Warhol scene,[32] and his confrontational stage act from the methods of the Living Theatre.[33] Iggy Pop’s vile and self-destructive stage persona became the model for the later punk rock performers of the ‘70s. In American culture at least, much of the aesthetics of ‘homosexual evil’ can be traced back to the work of filmmaker Kenneth Anger,[34] whose book Hollywood Babylon, focusing on the dark and degraded subhistory of Hollywood glamour, is the bible of camp.[35] Anger’s films detailing various American subcultures seen through a homosexual gaze set the standard for much pop art following in the Warholian tradition.

It is through Kenneth Anger that the leather-clad 1950s juvenile delinquent, with his emotion-laden pop songs, finds his way into the camp pantheon,[36] enters the Velvet Underground, and finally comes to rest in the leather uniform of punk. His influence also helped convert the macho posturings of the biker thug into a sign of the alienated and sensitive artist—witness Patti Smith’s image mix of leather boy and romantic poet. Likewise, it is through Anger, whose interest in popular subcultural ritual led him to ritual magic, that Satanism—as another sign of decadence—enters the pop music world[37] (primarily through the Rolling Stones in their psychedelic period, when they adopted Anger’s look lock, stock, and barrel).[38]

Mike Kelley, Unisex Love Nest, 1999. Installation view, Galerie Daniel Bucholz, Cologne, Germany, 2000. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY

Mike Kelley, Unisex Love Nest, 1999. Installation view, Steirischer Herbst 99, Palais Attems, Graz, Austria, 1999 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY

What becomes of this ‘outing’ of the abject nature of the feminine, consensually precipitated in music and avant-garde cultures?[39] As ‘transvestite’ counterculture leaves the utopianism of the 1960s behind and enters the economically harsher social climate of the 1970s, two major trends emerge: feminism and punk. In the context of all this female posturing, it only makes sense that female artists would finally demand to play a role. Even though there were female members of such ‘transvestite-oriented’ groups as the Cockettes—and the various versions of the Ridiculous Theater in New York[40]—the outward signs of most of the costuming were female-coded. Some of the female artists involved with these theater companies describe their experiences as a kind of self-exploration in relation to conventions of glamour.[41]

As participants in the antipatriarchal tenor of the period, they were not particularly interested in experimenting with the adoption of male gender stereotypes. With her overtly S&M persona as the whip dancer with the Velvet Underground, her ‘butch’ roles in Warhol’s films, and her masculine portrayals in John Vaccaro’s plays, Mary Woronov is the exception here.[42] More commonly, the female participants were primarily concerned with their own relationship to female stereotypes. The GTOs, for example, invented a look that was a trash version of the female Hollywood stars of the 1920s and 1930s.[43] Like the Warhol ‘star system,’ this was meant as a retooling, or redefinition, of that beauty, yet was still tied to it through the inversions of camp.[44]

Several female artists in the early 1970s began to experiment with shifting roles and identities in relation to issues of glamour and gender. Eleanor Antin, for example, made a work titled Representational Painting (1971), for which she sat in front of a mirror applying makeup, removing it, and applying it again in a constant state of ‘pictorial’ self-definition.[45] She later adopted a series of overtly theatrical personas, including a king, a nurse, and a ballerina.[46] This kind of play reached its zenith in Judy Chicago’s feminist workshop programs in the Los Angeles area in the early 1970s.[47] Here, female artists collectively explored their relationship to various female stereotypes in a much more critical and politically conscious environment than had previously been possible. Their performances used such stereotypes as the cheerleader, bride, waitress, beauty queen, and drag queen as a way of exploring and destabilizing female stereotypes.

Mike Kelley, Cross Gender / Cross Genre (still), 1999 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY

Mike Kelley, Cross Gender / Cross Genre (still), 1999 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY

The rise of glam rock was concurrent with this movement. In America at least, Alice Cooper is a key transitional figure, in that he leaves psychedelia behind and fully embraces the frameworks of pop—trying, that is, to balance irony and popular appeal. Glam rock was a music that fully understood the commercial music world and accepted it as an arena of facade and emptiness, using the image of the drag queen as a sign of this status. David Bowie is crucial here.[48] He adopts personas, throws them away at whim, and constantly reinvents himself for the market. He mirrors our culture of planned obsolescence. For consumer culture, it has been suggested, the constantly changing, chameleon persona represents empowerment. Certain feminist critics have read Madonna’s activities in this way, though I have serious misgivings about this interpretation of her practice—or of Bowie’s.[49]

Madonna becomes the sign of a spectacular female producer, in contrast to the traditional image of the passive female consumer. I might add that this is how the GTOs thought of themselves: as consumers—groupies—who became producers—rock stars themselves.[50] The spectacular is engaged head-on through pure emulation. Punk was the immediate response to this fixation with spectacular consumer culture; it replaced the spectacular with the pathetic.[51] Punk was the last gasp of avant-gardism in pop, played out with the most extreme signs of decadent nihilism. As a symbol of this end state, the gender significations of the previous avant-garde were reversed: maleness became the general referent. The punk uniform is the macho rough trade look of Kenneth Anger’s camp leather boy—for men and women alike. Androgyny remains a factor here, but whether the punk ‘unisex’ image was a vestige of some connection to the utopian, feminine androgyny of the psychedelic period, or is simply consistent with the capitalist cult of youth culture, is open to argument. But that’s another story.

Mike Kelley, 1999 – Twenty years after its creation, Mike Kelley’s ‘Unisex Love Nest’ will be presented in the late artist’s hometown for the very first time when it fills Hauser & Wirth’s stand at the inaugural Frieze Los Angeles. Mike Kelley’s ‘Cross Gender / Cross Genre’ (1999, 120 min) includes interviews by Mike Kelley, Diedrich Diedrichsen, and Juliane Rebentisch, and is edited by Catherine Sullivan and Greg Kucera, with graphics by Salvatore Reda and Michelle Alperin. Special thanks to Eleanor Antin, Jackie Apple, Pamela Des Barres, A.A. Bronson, Rodney Bingenheimer, Stephanie Farrago, Cameron Jamie, Gerard Malanga, Roger Niren, Sebastian, Jim Shaw, Mink, Stole, Mary Woronov, and Holly Woodlawn. Courtesy Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY.

1. The poet and punk rock musician Richard Hell recorded Blank Generation in 1976 (Ork Records). His intentions, signaled in the song’s title, differed from its general reception: “People misread what I meant by ‘Blank Generation.’ To me, ‘blank’ is a line where you can fill anything in. It’s positive. It’s the idea that you have the option of making yourself anything you want, filling in the blank. And that’s something that provides a uniquely powerful sense to this generation. It’s saying, ‘I entirely reject your standards for judging my behavior.’“ Cited in Clinton Heylin, From the Velvets to the Voidoids: A Pre-Punk History for a Post-Punk World (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), p. 123.2. The core White Panther texts are collected in John Sinclair, Guitar Army: Street Writings/Prison Writings (New York: Douglas Book Corporation, 1972).3. Key Yippie publications include: Abbie Hoffman, Revolution for the Hell of It (written under the pseudonym Free) (New York: Dial Press, 1968); Abbie Hoffman, Woodstock Nation: A Talk-Rock Album (New York: Vintage Books, 1969); Jerry Rubin, Do It (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1970); and Jerry Rubin, We Are Everywhere (New York: Harper and Row, 1971).4. “The whole push of the industrial world is to enslave people. The corporations are just modern versions of the old feudal system—in fact they call the factories ‘plants,’ which is short for ‘plantation,’—you dig? . . . Take LSD a few times and you become physically incapable of having anything to do with it.” John Sinclair, cited in “The Penitentiary Ain’t Shit to Be Afraid Of: Interview with Peter Steinberger” (1972), in Sinclair, Guitar Army, p. 182.5. For a history of the rise of American psychedelic culture, see Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams: The CIA, LSD, and the Sixties Rebellion (New York: Grove Press, 1985).6. On psychedelic music, see Vernon Johnson, The Acid Trip: A Complete Guide to Psychedelic Music (Todmorden, Lancashire: Babylon Books, 1984); Gene Sculatti and Davin Seay, San Francisco Nights: The Psychedelic Music Trip 1965–1968 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985); Jim DeRogatis, Kaleidoscope Eyes: Psychedelic Rock from the ‘60s to the ‘90s (Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1996).7. On camp, see Susan Sontag’s seminal essay “Notes on Camp” (1964), in Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), pp. 277–93; on Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol, see Phillip Monk, “Beat Brando, Camp Brando,” in American Playhouse: The Theatre of Self-Presentation (Toronto: The Power Plant, 1998), pp. 15–27; see also Kim Michasiw, “Camp, Masculinity, Masquerade,” in Elizabeth Weed and Naomi Schor, eds., Feminism Meets Queer Theory (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), pp. 157–86.8. “A new consciousness is rising out of the morass of a declining society that has bent too far toward rationalism, toward technology and toward the acquisition of power through unbridled competition. . . . The new consciousness takes note that our society has become overbal-anced in favor of the so-called ‘masculine’ qualities of character. The new orientation that is gaining influence may be characterized as emphasizing ‘feminine’ values, or values that in the past, at least, have been associated more with the feminine than with the masculine. Among these values is a preference for cooperation rather than competition, for a team approach to problems rather than a strictly individualistic approach, for giving credit to intuition at times over and above a deliberate thinking process, and for emphasizing sexuality and relationship over and above power and violence.” June Singer, Androgyny: Toward a New Theory of Sexuality (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, 1977), p. 15.9. “The pig police are the shock troops of cultural repression and as such are extremely interested in snuffing out even the external manifestations of our culture. They pretend they are ‘only doing their job,’ but they follow our cultural developments very closely and get their weird sexual kicks by arresting and beating freeks and other new people. They can’t just fuck, they have to try to stop other people from fucking (which will never work) and from even saying ‘fuck.’ They seem to have no other sex life. . . . They get their rocks off by arresting us for getting ours off however naturally we can, and by any means necessary. They are sick, insane, perverted PIGS who can’t stand to see us having a good time even as we struggle for our freedom. They hate us and everything we do or stand for. They want to cut our hair off be-cause it shows them that we are free from the honkie work ruse and the perverted standards of ‘manliness’ and ‘femininity’ they use to keep people trapped in inhuman sexual roles.” John Sinclair, “Our Culture Is a Revolutionary Culture” (1969), in Sinclair, Guitar Army, pp. 148–49.10. “It is because it is not too far removed from the binarism of phallic power that becoming-woman can play this intermediary role, this role as mediator vis-à-vis other sexed becom-ings. In order to understand the homosexual, we tell ourselves that it is sort of ‘like a woman.’“ Félix Guattari, “Becoming-Woman,” in François Peraldi, ed., “Polysexuality,” Semiotext(e) 10 (Autonomedia, 1981), p. 87.11. For an overview of glam rock, see Barney Hoskyns, Glam!: Bowie, Bolan, and the Glitter Rock Generation (New York: Pocket Books, 1998).12. On Jack Smith, see J. Hoberman, “The Theatre of Jack Smith,” The Drama Review, no. 81, pp. 3–12; Stefan Brecht, Queer Theatre (New York and London: Methuen, 1986), pp. 10–27 and pp. 157–77; Edward Leffingwell et al., Flaming Creature: Jack Smith, His Amazing Life and Times (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1997). Smith’s writings are collected in Wait for Me at the Bottom of the Pool: The Writings of Jack Smith, ed. J. Hoberman and Edward Leffingwell (New York: High Risk, 1997).13. The Cockettes appear in performance in the underground films Palace (1971), dir. Scott Runyon and Syd Dutton, which documents the Cockettes’ first Halloween show, Les Ghouls, at the Palace Theatre in San Francisco; Tricia’s Wedding (1971), dir. Sebastian; and Luminous Procuress (1971), dir. Steven Arnold. Other films by Arnold include Messages, Messages (1972) and Flesh Garden (1974). A biographical sketch is provided in Peter Weiermair, Steven Arnold: ‘Exotic Tableaux’ (Kilchberg/Zurich: Stemmle, 1996), pp. 9–13. See also the recent documentary The Cockettes (dir. David Weissman and Bill Weber, 2001), GranDelusion Productions.14. The following exchange is from an interview by Mike Kelley with Sebastian, conducted in 1999. Mike Kelley: Can you say a little bit about how the Cockettes developed their cross-dressing aesthetic? They are interesting in that their look seems to be a mix of drag and hippie cultures. Sebastian: Exactly. That was really them. I don’t know how they came up with it, but it was certainly original at the time. The only drag that you saw in San Francisco then was the typical drag show where they would pull off the wig at the end, and the Cockettes were to-tally different from that. A lot of them had beards. It was like a sketch; a sketch doesn’t always tell the full story, but it gives you the idea. And this idea was in itself somewhat revolutionary. And, also, they weren’t just men dressing as women—there were plenty of women in the group too. Sometimes they played men’s roles, but quite often they didn’t. They liked to call themselves “The Theatre of Sexual Role Confusion.” I always liked that term a lot. It’s much better than “gender-bender.”15. On John Waters, see Brecht, Queer Theatre, pp. 137–56. Also John Waters, Crackpot: The Obsessions of John Waters (New York: Random House, 1987) and Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste (New York: Dell, 1981).16. “Unlike kitsch-attribution, then, camp-recognition doesn’t ask, ‘What kind of debased creature could possibly be the right audience for this spectacle?’ Instead, it says what if: What if the right audience for this were exactly me? What if, for instance, the resistant, oblique, tangential investments of attention and attraction that I am able to bring to this spectacle are actually uncannily responsive to the resistant, oblique, tangential investments of the person, or of some of the people, who created it? And what if, furthermore, others whom I don’t even know or recognize can see it from the same ‘perverse’ angle?” Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), p. 156. 17. For a discussion of gender readings and the social role of the artist, see chapter 2, “Wom-en and Artists, Students and Teachers,” in Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), pp. 41–66.18. On Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, see Michael Grey, Mother! The Story of Frank Zappa (London: Plexus, 1993); Frank Zappa with Peter Occhiogrosso, The Real Frank Zappa Book (New York: Poseidon Press, 1989); and Ben Watson, Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play (London: Quartet, 1993).19. On the relationship of Zappa’s music to Varèse, see Watson, Frank Zappa, pp. 4–8,46–61.20. For a description of Mothers of Invention shows at the Garrick Theatre, New York, in 1966, see ibid., pp. 87–88; for the bigger concerts of the late 1960s, see Grey, Mother!, pp. 88–89.21. For the views of Zappa (and others) on the Freak Scene, which Pamela Des Barres describes as “postbop, prepop,” see Watson, Frank Zappa, pp. 33–35.22. In 1967 and 1968 Zappa started two record labels, Bizarre and Straight, and released albums by Alice Cooper, Captain Beefheart, the GTOs, Lenny Bruce, Lord Buckley, and the street musician Wild Man Fischer, among others.23. On the cover of the album We’re Only in It for the Money (1968), the Mothers pose, in drag, in a tableau that parodies the cover of the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Members of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band wear women’s clothes in photos on the cover of the album Trout Mask Replica (1969).24. In Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety (New York: Routledge, 1992), Marjorie Garber puts it like this: “If ‘woman’ is culturally constructed, and if female imperson-ators are conscious constructors of artificial and artifactual femininity, how does a ‘female impersonator’ differ from a ‘woman’? The question seems both ludicrous and offensive, but its theoretical and social implications are large and important. Female impersonators are often accused of misogyny (and regularly deny the charge), but in the female impersonator, the feminist debate about essentialism versus constructedness finds an unexpected, parodic, and unwelcome test” (pp. 354–55).25. See Alice Cooper and Steven S. Gaines, Me Alice: The Autobiography of Alice Cooper (New York: Putnam, 1976).26. Alice Cooper’s hit singles in the 1970s include “I’m Eighteen” (1971), “School’s Out” (1972), “Elected” (1973), “No More Mr. Nice Guy” (1973), and “Only Women Bleed” (1975).27. Liberace writes about his lawsuit against the London Daily Mirror gossip columnist “Cassandra” in his book Liberace: An Autobiography (New York: Putnam, 1973).28. Garber, again (Vested Interests, p. 367): “Elvis’s appearance at the Grand Ole Opry, at the very beginning of his career, provoked a double scandal. His music was too black, and he was wearing eyeshadow. He was not asked back. For Chet Atkins, soon to become organizer of Elvis’s recording sessions in Nashville, the one lingering memory of Elvis at the Opry was his eye-makeup. ‘I couldn’t get over that eye shadow he was wearing. It was like seein’ a couple of guys kissin’ in Key West.’“29. “If Mick Jagger and Brian Jones used camp principally to underscore their basic machismo, when the Stones dressed in drag for their ‘Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow’ promo film, they were merely ridiculing female stereotypes—they none the less created a climate in which boys could flirt with homosexuality as a mode, a pose. Jagger’s wiry androgyny was a potent rejection of ‘straight’ masculinity, heavily inspired by the foppish bisexual aristocrats with whom the Stones were consorting.” Hoskyns, Glam!, p. 12.30. On Jim Morrison and the Doors, see Jerry Hopkins and Daniel Sugerman, No One Here Gets Out Alive (New York: Warner Books, 1980).31. See Iggy Pop, I Need More (Los Angeles: Thirteen Sixty-one, 1996); chapter 3, “Energy Freak-Out Freeform (1968–71),” in Heylin, From the Velvets to the Voidoids, pp. 32–43. The best source for information on the Stooges is probably “I Wanna Be Your Dog: 1967–1971,” in Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain, Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk (New York: Grove Press, 1996), pp. 27–86.32. Poet, photographer, and assistant to Andy Warhol in the Factory, Gerard Malanga performed as a bullwhip dancer (along with Mary Woronov and Ronnie Cutrone) with the Velvet Underground as part of Warhol’s multimedia show “The Exploding Plastic Inevitable.” Malanga’s trademark at the time was his leather pants. “Jim Morrison came to see us at the Trip, because he was a film student in LA at the time. That’s when, as the theory goes, Jim Morrison adopted my look—the black leather pants—from seeing me dancing on stage at the Trip.” Gerard Malanga cited in McNeil and McCain, Please Kill Me, p. 17.33. Jim Morrison was charged with indecent exposure and other crimes after a concert with the Doors in Miami in 1969. He had been to a performance of Paradise Now by the Living Theatre shortly before this concert; see Hopkins and Sugerman, No One Here, pp. 222–23.34. On Anger, see Bill Landis, Anger: The Unauthorized Biography of Kenneth Anger (New York: Harper Collins, 1995).35. Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon (San Francisco: Straight Arrow Books, 1975) was originally published in France by J. J. Pauvert, Paris, in 1959.36. In Scorpio Rising (1964), Kenneth Anger’s ironic, sentimental portrait of rebel biker culture, the soundtrack is composed of such then-current pop songs as “Fools Rush In” by Ricky Nelson and “Blue Velvet” by Bobby Vinton.37. “Anger’s use of Brando (in film snips from The Wild One in Scorpio Rising) allowed the filmmaker to continue his Luciferian themes of disobedience in a more recognizable image of delinquency, now pop cultural rather than esoteric. Satanism having become pop cultural by the late 1960s, the theme would resurface without disguise in Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother in 1969.” Monk, “Beat Brando,” p. 24.38. In their promo film for Jumping Jack Flash and on the cover of the album Their Satanic Majesties Request, the Stones’ look is overtly Angeresque. “The Stones own ‘flirtation’ with evil continued when Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Marianne Faithful became involved with Kenneth Anger’s infamous Lucifer Rising, eventually released with a prison-recorded soundtrack by Manson acolyte Bobby Beausoleil. Jagger was supposed to play Lucifer to Richard’s Beelzebub but—in Anger’s own words—’backed away from being identified with him.’ ‘Kenneth had a very conscious influence over the Stones,’ Marianne Faithful told Mick Brown. ‘I think he thought Mick and the rest of the group could embody his vision.’“ Barney Hoskyns, Waiting for the Sun: Strange Days, Weird Scenes and the Sound of Los Angeles (New York: Penguin, 1996), p. 175.39. “I do not want to simply equate abjection with the feminine, but rather to acknowledge how patriarchal notions of femininity have been adopted for transgressive means. For, as Kristeva asks, ‘does not the combat against the phallic sign and against an entire monological culture finally sink into the substantial cult of woman?’ Here one must remark, however, that what con-notes the ‘cult of woman’ (or the ‘feminine’) may have absolutely nothing to do with women; within a patriarchal society it connotes, rather, that which is not man. (For example, the ‘feminine’ connotes the body, nature, passivity, amorphousness versus man’s mind, culture, activity, form.) If one accepts, then, the transgressive to be feminine and strives for a situation where ‘everyone and everything becomes Woman—as a culture obsessively turns itself inside out—where does that leave women?’ The privileging of the feminine in a transgressive discourse by no means guarantees liberation.” Leslie C. Jones, “Transgressive Femininity: Art and Gender in the Sixties and Seventies,” in Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art/D. A. P., 1993), p. 34.40. The term “Ridiculous Theater” has been used generically to describe the theater works of Charles Ludlum, Ronald Tavel, and John Vaccaro; see Brecht, Queer Theatre, and Bonnie Marranca and Gautam Dasgupta, Theatre of the Ridiculous (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).41. Interviewed by Kelley in 1999, the performance artist Jacki Apple notes: “So the question was, could power exist within the same framework as beauty as defined by the culture at large—as glamour? So we decided to experiment with this. And of course the place that we had to look wasn’t in the images of the ‘60s à la Twiggy, which is an androgynous kind of image and did not represent power but more of a kind of adolescent—and all of fashion in the ‘60s sort of remade woman in a girl image, you know, with Mary Jane shoes and little puff-sleeve dresses. So the place we had to go back to for that coalition, that merging, of power and beauty was basically to the films of the ‘40s—to the powerful, glamorous movie stars of the ‘40s.”42. Woronov’s most famous roles are Hanoi Hanna in Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls (1966) and Tamburlaine in John Vaccaro’s production of Charles Ludlum’s Conquest of the Universe (1967). For Woronov’s own account of her years in the Warhol scene, see Mary Woronov, Swimming Underground: My Years in the Warhol Factory (Boston: Journey Editions, 1995). Stefan Brecht enthuses about Woronov in Brecht, Queer Theatre, pp. 56–59.43. On the GTOs, see Pamela Des Barres, I’m with the Band: Confessions of a Groupie (New York: Morrow, 1987).44. “Warhol’s second-period films, all in sound, were vehicles that he specially tailored for a new phenomenon—the underground superstar. Sensing the avant-garde cinema needed its counterparts to Hollywood’s legendary stars, Warhol began to establish a stable of performers comparable to that of the old studio system. Between the final weeks of 1964 and the early months of 1965, he ushered in a new era of cinematic glamour with films constructed around the personalities of two underground movie queens: Mario Montez, a female impersonator, and Edie Sedgwick, a scintillating young socialite. Montez, representing a perverse inversion of movie-star attractiveness, contributed a new element of absurdity to Warhol’s already controversial reputation, while Sedgwick gave him a chic respectability among the socially prominent.” David Bourbon, Warhol (New York: Abrams, 1989), p. 196. Jackie Curtis, another Warhol transvestite superstar, talks about his/her relationship with Holly-wood glamour in Blair Sabol and Lucian K. Truscott IV, “The Politics of the Costume,” Esquire, no. 75 (May 1971), p. 133: “The costume for Jackie is a critical part of her lifelong desire to be a star. In the facing photograph, she is sporting the bodice worn by Lana Turner in The Prodigal and feathers which once belonged to Marlene Dietrich. The setting is Ruby Shoes Day, a Village shop featuring properties acquired at last year’s M-G-M auction. [Jackie Curtis said,] ‘Being a star occupies every moment of my existence. Imagine how it feels to look like Rita Hayworth and feel like the reincarnation of James Dean. Hell—that’s what. When you feel that way there’s nothing left for you to do but go out there and star.’“45. Eleanor Antin, Adrian Piper, Martha Wilson, and Jacki Apple all made work involved with role playing; see Lucy R. Lippard, “Making Up: Role Playing and Transformation in Women’s Art” (1973), in From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1976), pp. 101–08.46. A major retrospective, Eleanor Antin, curated by Howard Fox, was put on at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1999.47. See Faith Wilding, By Our Own Hands: The History of the Women Artist’s Movement, Southern California 1970–1976 (Los Angeles: Double X, 1977). See also Moira Roth, The Amazing Decade: Women and Performance Art in America 1970–1980 (Los Angeles: Astro Artz, 1983); and Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact (New York: Abrams, 1994). 48. See Henry Edwards and Tony Zanetta, Stardust: The David Bowie Story (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1986).49. This is Garber (Vested Interests, pp. 126–27) on Madonna: “But the moment (at a per-formance on a video awards show) that scandalized critics was a moment of sheer quotation from Michael Jackson, when Madonna danced toward the audience and squeezed her crotch. Now, in video and live dance performance Michael Jackson often makes this kind of theatrical gesture, and no one ever complains—quite the contrary. But Madonna, squeezing what she hadn’t got (or had she?), emblematized the Lacanian triad of having, being, and seeming. Squeezing the crotch of her pants became for her, onstage, the moment of the claim to empowered transvestism, to seem rather than merely to have or to be—not (and this distinction is important) just a claim to empowered womanhood. In this moment, and in the very fact that she chose the cross-dressed costume from her longer video to present at the opening of the awards show, Madonna became transvestism itself, the more so since she was, apparently, so deliberately troping off Michael Jackson.”50. “Not too long ago, the GTOs arrived at the A&M Records studios for a photo session. They looked about the way they usually look: full freak. And on this day there seemed to be a sartorial leaning toward the 1940s in style and cut. . . . What the GTOs have going for them is, really, a dream come true. Now they’re a group! Now they’re making records! Now they’re appearing in public. Now they’re being interviewed and written about and photographed. It’s as if they’d become the stars they’d so long worshipped.” John Burks and Jerry Hopkins, Groupies and Other Girls (New York: Bantam, 1970), pp. 78–79.51. In 1970, Lester Bangs had already anticipated the rise of the pathetic rock movement that came to be called punk. This is from a review of the Stooges, the godfathers of punk: “What we need are more rock ‘stars’ willing to make fools of themselves, absolutely jump off the deep end and make the audience embarrassed for them if necessary, so long as they have not one shred of dignity or mythic corona left. Because then the whole damn pompous edifice of this supremely ridiculous rock n’ roll industry, set up to grab bucks by conning youth and encouraging fantasies of puissant ‘youth culture,’ would collapse, and with it would collapse the careers of the hyped talent-less nonentities who breed off of it.” Lester Bangs, “Of Pop and Pies and Fun: A Program for Mass Liberation in the Form of a Stooges Review, or Who’s the Fool?” (1970), in Lester Bangs, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), p. 34.