In collaboration with the Comité Picabia, we present an exhibition of over 40 post-war artworks by Francis Picabia. Curated by Beverley Calté and Arnauld Pierre, this will be the first major solo exhibition exclusively exploring Picabia’s unique final period, created after his return to Paris in 1945 until the year before his death in 1953. Often overshadowed by other periods of his oeuvre, Picabia’s last series saw the artist abandon his famous wartime Nudes, coupled with a particular interest in surface texture and new sources of inspiration. Characteristic of Picabia’s restless artistic talent, these paintings represent his own definitions of nonfigurative art, creating a new visual language which distinctly sets this bold group of works apart from anything he had done before. This exhibition will travel to Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street from 1 May – 25 July 2025.

EXPLORE THE EXHIBITION

The final phase of Picabia’s work, whose prolific career was marked by a ‘complex alternation of styles and techniques’ (Arnauld Pierre), is reflective of an unprecedented visual language and a singular approach to abstraction. This period testifies to the artist’s unwavering commitment to a core principle, a method that has persisted through all his transformations: the use of pre-existing visual material. This material was drawn either from a vast collection of images or from his own earlier paintings, which he continued to revisit.

Ursula presents a new film exploring the mysterious paintings from Francis Picabia’s final years

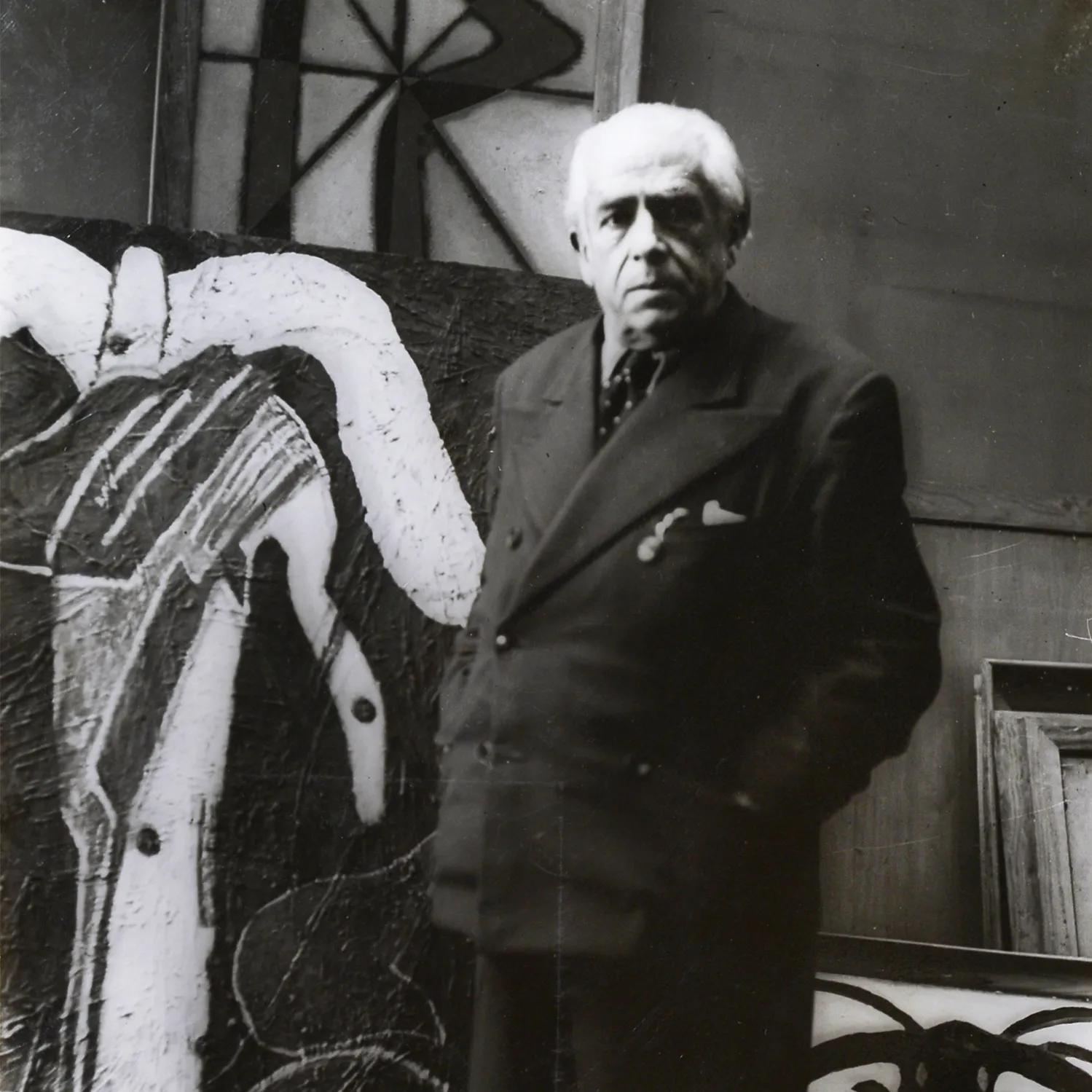

Picabia in his studio at 26 rue Danielle-Casanova, Paris, ca. 1948 – 49; Picabia’s studio in Paris as published in Raymond Bayer, Entretiens sur l’Art abstrait, Geneva: Éditions Pierre Cailler, 1965, pp. 256 – 57. Archives Comité Picabia, Paris

In 1945, Picabia returned to Paris, facing challenging economic and artistic circumstances and needing a fresh start. The painter appeared to return to the Dada ‘anti-painting’ ethos of the past. The most striking examples of this resurgence are found in his Points series, which were controversially reviewed by critics. Works include ‘Silence’ (1949) or ‘Six points’ (1949), in which a handful of dots—resembling a constellation—is set against a monochrome background subtly clouded by surface effects, resembling turbulent currents or signs of wear and tear.

During this period, Picabia was far from a recluse. On Sundays, he regularly opened his studio to artists like Henri Goetz, Christine Boumeester, Raoul Ubac, Jean-Michel Atlan and Georges Mathieu. These figures sought to forge a third path, particularly at the Salon des Surindépendants, between the legacies of Surrealism and the rigors of abstraction. While Picabia resisted being confined to group labels, he was nonetheless willingly associated with the ‘informels’ in the post-war period.

‘Picabia obstinately followed his own path, a characteristic of his provocative individualism and indifference toward trends of the moment.’—Beverley Calté

This connection is perhaps best justified by his distinctive treatment of the material, the very substance of the painting. This can be seen, for example, in ‘Rapport avec les vertus (In Relation to the Virtues)’ (1949), with its dark colored areas that defy the uniformity of a flat field, or in ‘Colloque (Colloquium)’ (1949), with its sharp folds and textured impasto.

Picabia remained steadfast in following his own path and the post-war period was no exception. He continued to employ his tried-and-tested technique of sampling, borrowing and assimilating. Notably, the exhibition highlights the role that prehistoric artistic sources had in Picabia’s paintings during the time. This inclination towards mythologized origins can manifest as an expected engagement with the forms and teachings of the African continent or Oceania.

Masks became one of Picabia’s particularly favored motifs, as seen in ‘Niagara’ (ca. 1947), where a cranial form swells into a bulb and is divided into three sections by a Y-shaped groove. The mask motif reminds us that this final phase of Picabia’s work, often labelled ‘abstract,’ was not entirely so. Alongside the masks, the exhibition features ‘Villejuif [I],’ an oil on wood from 1951. Its evocative power and emotional resonance remain undeniable.

Picabia’s collection of imagery was not restricted to distant geographical sources. Catalan Romanesque art, along with prehistory, were among the artist’s favorite inspirations. His borrowings also included ‘self-borrowings,’ as seen in his repainted works, such as ‘Elle danse (She Dances)’ (1948). Picabia also appropriated words, often drawing on Nietzsche for his titles. Examples include ‘Cherchez d’abord votre Orphée ! (First Seek Your Orpheus!)’ (1948) and ‘Le négateur du hasard [?] (The Denier Of Chance [?])’ (1946), both inspired by ‘Le Gai Savoir.’ This approach is hardly surprising—until the very end of his life, Picabia made his own rules when it came to aesthetics.’

From Hauser & Wirth Publishers

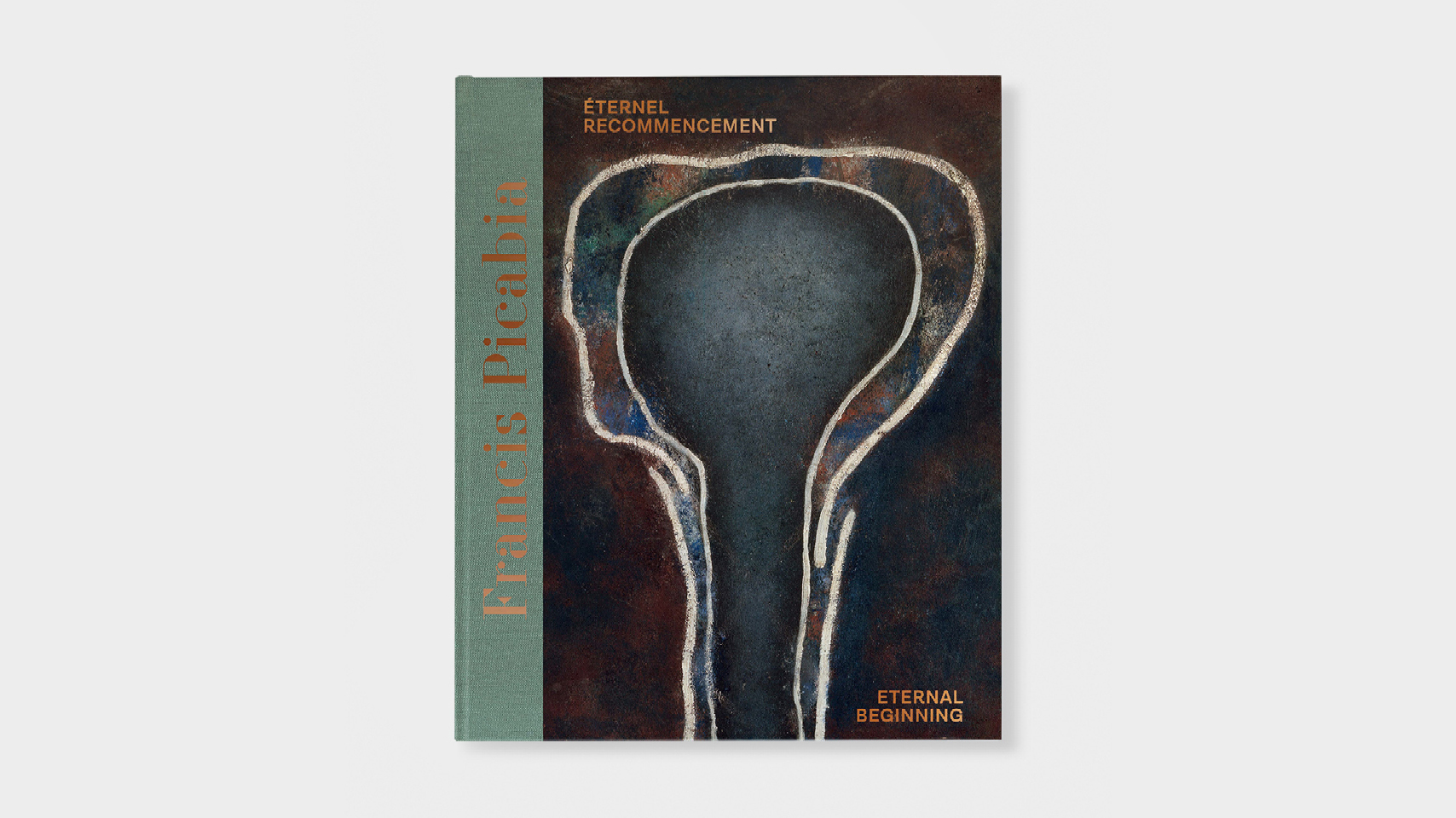

FRANCIS PICABIA: ÉTERNEL RECOMMENCEMENT / ETERNAL BEGINNING

Prefaced by Beverley Calté, president of the Comité Picabia, this book delves into Picabia’s practice between the years 1945 to 1952—an incredibly rich period during which Picabia created paintings unlike anything he had produced before, working alongside the growing Art Informel movement in Paris.

Sobre el artista

Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia was born François Martinez Picabia in Paris, to a Spanish father and a French mother. After initially painting in an impressionist manner, elements of fauvism and neo-impressionism as well as cubism and other forms of abstraction began to appear in his painting in 1908, by 1912 he had evolved a personal amalgam of cubism and fauvism. In 1915—which marked the beginning of Picabia’s machinist or mechanomorphic period—he and Marcel Duchamp, among others, instigated and participated in dada manifestations in New York. For the next few years, Picabia remained involved with the dadists in Zurich and Paris, but finally denounced dada in 1921 for no longer being ‘new.’ The following year, he returned to figurative art, but resumed painting in an abstract style by the end of World War II.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 9