Fabric Works

8 July - 9 September 2023

St. Moritz

About

‘Fabric Works’ brings together a selection of artworks by a cross generational group of artists from the gallery’s program who have used textiles to push the limits of their respective mediums. Contemporary works by Phyllida Barlow, Frank Bowling and Pipilotti Rist are displayed alongside modern masters, including Louise Bourgeois, Alina Szapocznikow, Piero Manzoni and Fausto Melotti. The painterly works on view are sewn, patched and haptic, eliciting fundamental questions about the cross-fertilization of sculpture and painting. Sculptural pieces display unconventional elements of pliability, familiarity and intimacy, challenging associations about the materiality of sculpture.

Exploring emotions, psychological states and memories, the work of Pipilotti Rist and Louise Bourgeois exists in a space between the visual and the sensual. Rist’s sculptural installation ‘Yayoi, die erleuchtete Enkelin (dunkelblau pink) (Familie Elektrobranche)’ (2022) utilizes a swimsuit lit-up from within like a hanging lamp. Focusing attention on the torso, with the fabric becoming a translucent skin, the form rounds off into the hips—an area which is believed to be a storage vessel for emotions, from passion to vexation. Rist gives this heavy area of the body a lightness by making it hollow and illuminated. Speaking on her affinity for using recycled objects, the artist says, ‘The material has stories in it already, lives from other uses, but the tradition also gives a sense of caring, paying attention, thinking twice.’

Download Press Release

Download Press ReleaseAbout the Artists

Phyllida Barlow

For almost 60 years, British artist Phyllida Barlow took inspiration from her surroundings to create imposing installations that can be at once menacing and playful. She created large-scale yet anti-monumental sculptures from inexpensive, low-grade materials such as cardboard, fabric, plywood, polystyrene, scrim, plaster and cement. These constructions were often painted in industrial or vibrant colors, the seams of their construction left at times visible, revealing the means of their making.

Barlow’s restless invented forms stretch the limits of mass, volume and height as they block, straddle and balance precariously. The audience is challenged into a new relationship with the sculptural object, the gallery environment and the world beyond.

‘There’s something about walking around sculpture that has the possibility of being reflective, like walking through a landscape,’ Barlow has said. ‘The largeness of sculpture has that infinite possibility to make one engage beyond just the object itself and into other realms of experience.’

Barlow exhibited extensively across institutions internationally and in 2017 represented Britain at the Venice Biennale.

Frank Bowling

For over six decades, Frank Bowling has relentlessly pursued a practice which boldly expands the possibilities and properties of paint. Ambitious in scale and scope, his dynamic engagement with the materiality of his chosen medium, and its evolution in the broad sweep of art history, has resulted in paintings of unparalleled originality and power. Bowling has been hailed as one of the foremost British artists of his generation. Born in British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1934, he arrived in London in 1953, graduating from the Royal College of Art with the silver medal for painting in 1962. By the early 1960s, he was recognized as an assured force in London’s art scene. During this period, his highly individual language of painting, which emerged from expressionistic figuration and pop art, encompassed autobiographical elements and the artist’s socio-political concerns.

Bowling went on to divide his time between the art scenes in London and New York, maintaining studios in both cities. This transatlantic orientation was to see his early engagement with expressive figuration and pop art shift to an immersion in abstraction which continues in his practice today. Visible in his work are the legacies of both the English landscape tradition and American abstraction from which Bowling honed a distinctive vocabulary, combining figurative, abstract and symbolic elements. As Bowling has explained, ‘I was always very conscious of scratching out and of new interpretations replacing the old; updating traditions.’

A major reorientation in Bowling’s practice came in 1966 when he relocated from London to New York, at a time when the artistic scene was divided along lines of formalism and politics. In New York, Bowling pushed his work in new directions. He met Jasper Johns and engaged in a dialogue with his contemporaries, such as Jack Whitten, Mel Edwards, Al Loving, and Daniel Johnson. In 1969, Bowling organized, curated, and wrote the catalogue essay for ‘5+1’, a notable exhibition at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, and Princeton University showcasing the work of five African American abstract artists as well as his own recent paintings. He expressed frustration at the critical invisibility of Black artists and the narrow parameters by which his art and that of his peers was being assessed. Through his writings, as a contributing editor of Arts Magazine (1969-1972), he resisted what he saw as the reductive categorization of ‘Black Art’ as purely political in subject matter, staking a claim for abstraction.

By 1971, Bowling’s visionary approach to painting fused abstraction with personal memories. Concerns of color, surface and process gained in prominence resulting in his iconic series of ‘Map Paintings’, which include the stenciled landmasses of South America, Africa and Australia and were exhibited that same year at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Over the years, the points of reference in his work reflect Bowling’s interest in a wide scope of art history, from Constable and Turner, to Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. From 1973 to 1978, Bowling experimented with ideas of chance and ‘controlled accidents’, pouring paint from a two-meter height to create his visually arresting ‘Poured Paintings’, an expansion from color field painting.

Bowling returned to London in 1975 but continued to spend significant periods in New York. His sculptural paintings of the 1980s include embedded objects (newsprint, plastic and foam) and thickly textured canvases, and have been described as evoking landscape, riverbeds, and geological strata. In 1986, he exhibited a group of major new paintings at the Serpentine Gallery in London, curated by Ronald Alley, then Keeper of Modern Art at the Tate Gallery. Bowling shares Turner’s and Constable’s preoccupation with light, which is never more evident than in his expansive ‘Great Thames’ series of paintings of the late 1980s.

Today, Bowling’s mastery of the painted medium and explorations of light, color, and geometry incorporate the use of ammonia and multilayered washes. His restless reinvention of the painted plane endures in his current bodies of work which continue to break new ground through his use of thick impasto textures, acrylic gels, collage, stitched canvas, and metallic and pearlescent pigments. Bowling works every day in his South London studio, accompanied by his wife, Rachel, other family members and friends, forever driven by his fascination with exploring the vast and radiant possibilities of paint.

Bowling’s work has been exhibited extensively which has cemented his place in the post-war canon of contemporary and modern art. A turning point in Bowling’s career came in 2003 when his ‘Map Paintings’, which had been in storage and unseen since the early 1970s, were the centerpiece of the exhibition ‘Faultlines: Contemporary African Art and Shifting Landscapes’, at the 50th Venice Biennale. His work drew much attention and paved the way for him becoming a Royal Academician in 2005. Bowling was awarded the OBE for Services to Art in 2008 and a knighthood in the Queen’s birthday honors in 2020. His work is represented in over fifty collections worldwide and has been exhibited in numerous group and solo exhibitions, including the 2017–19 touring exhibition ‘Mappa Mundi’, the hugely successful retrospective at Tate Britain in 2019 and the major exhibition 'Frank Bowling: Americas’ which toured from MFA Boston to SFMOMA in 2022 - 23. Bowling is the subject of a BBC documentary, ‘Frank Bowling’s Abstract World,’ which coincided with the opening of the Tate retrospective. In 2022, he was awarded the Wolfgang Hahn Prize which honors exceptional contemporary artists.

Pipilotti Rist

Pipilotti Rist, a pioneer of spatial video art, was born 1962 in Grabs in the Swiss Rhine Valley on the Austrian Border and has been a central figure within the international art scene since the mid-1980s.

Astounding the art world with the energetic exorcistic statement of her now famous single channel videos, such as ‘I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much,’ 1986 and ‘Pickelporno,’ 1992, her artistic work has co-developed with technical advancements and in playful exploration of its new possibilities to propose footage resembling a collective brain. Through large video projections and digital manipulation, she has developed immersive installations that draw life from slow caressing showers of vivid color tones, like her works ‘Sip My Ocean,’ 1996 or ‘Worry Will Vanish,’ 2014.

For Rist, showing vulnerability is a sign of strength on which she draws for inspiration. With her curious and lavish recordings of nature (to which humans belong as an animal), and her investigative editing, Rist seeks to justify the privileged position we are born with, simply by being human. Her installations and exhibition concepts are expansive, finding within the mind, senses and body the possibility for endless discovery and poetical invention. ‘Pixel Forest,’ 2016, made from 3,000 thousand LEDs hung on strings, resembles a movie screen that has exploded into the room, allowing viewers an immersive walk through 3-dimensional video. As she herself puts it, ‘beside the energy-intensive exploration of the geographical world, pictures, films and sounds have been and are the spaces into which we can escape... The projector is the flamethrower, the space is the vortex and you are the pearl within.’

Since 1984, Rist has had countless solo and group exhibitions, and video screenings worldwide. Her recent solo exhibitions are 'Electric Idyll' at the Fire Station Doha (2024), 'Prickling Goosebumps & A Humming Horizon' at Hauser & Wirth New York and Luhring Augustine Chelsea (2023-24), 'Behind Your Eyelid' at Tai Kwun Hong Kong (2022), ‘Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor’ at The Geffen Contemporary, MOCA, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (2021 – 2022), ‘Your Eye Is My Island’ at MoMAK, The National Museum of Modern Art Kyoto and ART TOWER MITO (2021). ‘Åbn min Lysning. Open my Glade’ at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art Humlebæk Denmark (2019), ‘Sip My Ocean’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney (2017 – 2018), ‘Pixel Forest’ at New Museum New York (2016 – 2017) and ‘Your Saliva is My Diving Suit of the Ocean of Pain’ at Kunsthaus Zürich (2016), all resulted in record-breaking attendance numbers for each institution. A major exhibition is planned for summer 2025 at UCCA Beijing.

Louise Bourgeois

Born in France in 1911, and working in America from 1938 until her death in 2010, Louise Bourgeois is recognized as one of the most important and influential artists of our time. For over seven decades, Bourgeois’s creative process was fueled by an introspective reality, often rooted in cathartic re-visitations of early childhood trauma and frank examinations of female sexuality. Articulated by recurrent motifs (including body parts, houses and spiders), personal symbolism and psychological release, the conceptual and stylistic complexity of Bourgeois’s oeuvre—employing a variety of genres, media and materials—plays upon the powers of association, memory, fantasy, and fear.

Bourgeois’s work is inextricably entwined with her life and experiences: fathoming the depths of emotion and psychology across two- and three-dimensional planes of expression. ‘Art,’ as she once remarked in an interview, ‘is the experience, the re-experience of a trauma.’ Arising from distinct and highly individualized processes of conceptualization, Bourgeois's multiplicity of forms and materials enact a perpetual play: at once embedding and conjuring emotions, only to dispel and disperse their psychological grasp. Employing motifs, dramatic colors, dense skeins of thread, and vast variety of media, Bourgeois's distinctive symbolic code enmeshes the complexities of the human experience and individual introspection.

Rather than pursuing formalist concerns for their own sake, Bourgeois endeavored to find the most appropriate means of expressing her ideas and emotions, combining a wide range of materials—variously, fabric, plaster, latex, marble and bronze—with an endless repertoire of found objects. Although her oeuvre traverses the realms of painting, drawing, printmaking, and performance, Bourgeois remains best known for her work in sculpture.

Bourgeois’s early works include her distinct 'Personages' from the late 1940s and early 1950s; a series of free-standing sculptures which reference the human figure and various urban structures, including skyscrapers. The ‘Personages’ served as physical surrogates for the friends and family Bourgeois had left behind in France, while also highlighting an interest in architecture dating back to her childhood. Her installation of these sculptures as clustered ‘environments’ in 1949 and 1950 foreshadowed the immersive encounters of installation art twenty years before the genre’s rise to prominence.

Bourgeois’s work was included in the seminal exhibition ‘Eccentric Abstraction,’ curated by Lucy Lippard for New York's Fischbach Gallery in 1966. Major breakthroughs on the international scene followed with The Museum of Modern Art in New York's 1982 retrospective of her work; Bourgeois's participation in Documenta IX in 1992; and her representation of the United States at the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993.

In 2001, Bourgeois was the first artist commissioned to fill the Tate Modern’s cavernous Turbine Hall. The Tate Modern’s 2007 retrospective of her works, which subsequently traveled to the Centre Pompidou in Paris; The Guggenheim Museum in New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; and The Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C., cemented her legacy as a foremost grande dame of late Modernism.

Header image: Louise Bourgeois, ARCHED FIGURE, 1993 © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

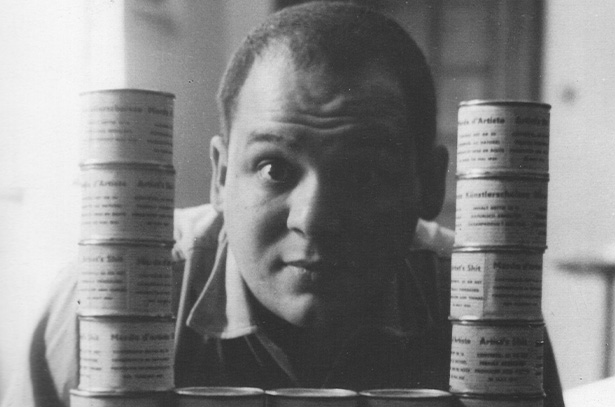

Piero Manzoni

The renowned Italian artist Piero Manzoni emerged as a powerful voice for the avant-garde in the 1950s, debuting as an artist at the ‘4a Fiera mercato: Mostra d’arte contemporanea’ in 1956. A self-taught painter, his work heavily featured anthropomorphic silhouettes and the impressions of objects. He began making his ‘white paintings’—later named ‘Achromes’—in 1957, at first with rough gesso and then with kaolin, as well as with creased canvases or surfaces divided into squares.

In 1959, the artist began his series which experimented with the display of inflated white balloons. The results—‘Corpi d’aria (Bodies of Air)' and ‘Fiato d’artista (Artist’s Breath),’ where balloons were poised on a tripod or wooden plinth—extended the creative experimentation first visualized in the ‘Achromes’ as Manzoni embarked upon works that used an entirely new visual language, reframing artistic interpretation. In July 1960, he presented ‘Consumazione dell’arte / dinamica del pubblico / divorare l’arte’ in Milan, during which he offered the public hard-boiled eggs with his thumbprint on them. By 1961, Manzoni was signing actual people, turning them into ‘living sculptures,’ and awarding them with a certificate of authenticity.

Alongside his work as an abstract avant-garde painter, Manzoni contributed to and collaborated with numerous artist groups and initiatives. As his artistic activity intensified, he began participating in group shows and signing manifestos alongside other artists, including Enrico Baj, Guido Biasi, Ettore Sordini, and Angelo Verga. For a period of time he embraced the Movimento Arte Nucleare, before abandoning it in 1958.

On several occasions, he showed his work with Agostino Bonalumi and Enrico Castellani, and he collaborated with artists of the Zero group in Düsseldorf and other European neo-avant-garde groups. In 1959, he founded the Galleria Azimut in Milan with Castellani, opening the gallery with an exhibition of his ‘Linee (Lines).’ The pair simultaneously published two issues of the Azimuth magazine. The second issue (1960) included one of Manzoni’s seminal texts ‘Libera dimensione’ or ‘Free dimension.’

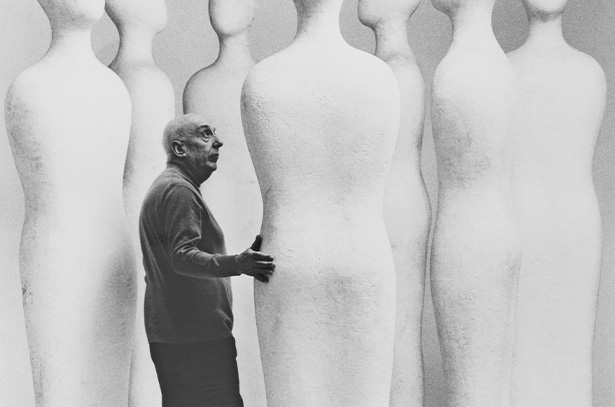

Fausto Melotti

Italian sculptor, painter and poet, Fausto Melotti is considered a pioneer of Italian art and is acknowledged for his unique contribution to the development of mid-century European Modernism. Coming of age in prewar Milan, and living through the horrors of the Second World War, Melotti metabolized wartime devastation in his work by returning to Renaissance principles of harmony, order, geometry, and musical structure, which he integrated into a highly personal yet universally accessible artistic language that expresses the full range of emotional experiences in modern human existence.

Before turning to art, Melotti studied music, mathematics and engineering—disciplines that exerted clear influence upon his distinctive practice across subsequent decades. Melotti trained as a figurative artist, studying under Italy’s leading Symbolist sculptor Adolfo Wildt at the Accademia di Brera in Milan. There he befriended fellow pupil Lucio Fontana in 1928, and in the following decade shifted his focus to abstraction and a new non-objective art. Melotti developed influential friendships with the Rationalist architects of Gruppo 7 and the abstract artists who gravitated around Galleria Il Milione. With Fontana, he joined the ‘Abstraction-Création’ movement, developing firm ideas about non-figurative art. Influenced by his education in engineering and music, Melotti’s first abstract sculptures were geometrical, and echoed the young artist’s academic training in order, rhythm, proportions and form.

Melotti’s ceramics of the 1940s respond to the pain, trauma, and despair that crowded his thoughts in the aftermath of the Second World War. Aerial bombings destroyed the artist’s studio in Milan and profoundly altered his artistic vision, precipitating a literal and symbolic rupture in his idealized pursuit of abstraction. His attention shifted to the craft and production of ceramics and terracotta. Rendered in polychromatic glazes, the enigmatic figures in these works illustrate the artist’s urgent and necessary return to figuration.

By the 1960s, Melotti had returned to sculpture, using a new language built upon delicate threads and thin sheets of brass, iron, and gold to express a more resolved and distinctly humanist sensibility. Delicately wrought, almost fragile constructions became enriched by a new narrative, dream-like and symbolic. These weightless works resemble aerial drawings incorporating space, air and transparency. His later work of the 1970s and 1980s is characterized by rhythmic geometric forms with an underlying humanist narrative that curator Douglas Fogle describes as ‘quivering just on the threshold between the solidity of figuration and the immateriality of abstraction.’

Current Exhibitions

1 / 11