Beginning 28 January 2016, Hauser & Wirth is pleased to present ‘No Life Lost’, an exhibition of recent sculptures and drawings by internationally admired Belgian artist Berlinde De Bruyckere. The centerpiece of the exhibition is De Bruyckere’s monumental project ‘Kreupelhout – Cripplewood, 2012 – 2013’ (2013), shown here for the first time in the United States. The largest and most ambitious work by the artist to date, this massive, darkly beautiful and acclaimed installation – a collaboration with Nobel Prize novelist J M Coetzee – debuted at the Belgian Pavilion of the 55th edition of the Venice Biennale in 2013.

Traditions of the Flemish Renaissance have exerted a profound influence upon Berlinde De Bruyckere’s art. Drawing from the legacies of the European Old Masters and Christian iconography, as well as mythology and cultural lore, the artist layers existing histories with new narratives suggested by contemporary world events to create a psychological terrain of pathos, tenderness and repulsion. Working with casts made of wax, animal skins, hair, textiles, metal and wood, she renders haunting distortions of organic forms – abstracted and contorted figures of fragile materials that achieve an almost alchemical metamorphosis into mortifying flesh. Through these works De Bruyckere grapples with the dualities of the human condition. In desire and suffering, horror and beauty, fragility and strength, hope and dismay, she locates a poetic grace that manages to endure in the ruins of the corporeal world. Her art is a powerful meditation upon the fundamental human search for transformation, transcendence and reconciliation in the face of mortality.

‘Berlinde De Bruyckere. No Life Lost’ will remain on view at Hauser & Wirth’s 511 West 18th Street location through 2 April 2016.

In conjunction with the exhibition, Hauser & Wirth is pleased to present the world premiere of ‘Sibylle’, a performance work by celebrated Portuguese contemporary dancer Romeu Runa, developed in collaboration with De Bruyckere and inspired by the new sculptures created for ‘No Life Lost’. Runa will perform the piece in five sets scheduled during the run of the exhibition: Saturday 30 January, 2 pm; Wednesday 24 & Thursday 25 February, 7 pm; Friday 1 April, 7 pm; Saturday 2 April, 2 pm.

The Exhibition ‘No Life Lost’ begins with a new suite of works on paper titled ‘Met tere huid’ (Of tender skin) (2015 – 2016). Rendered in watercolor and pencil, with bruised pinks and somber strokes of black, these drawings reference the bodily tones of freshly flayed animal skins.

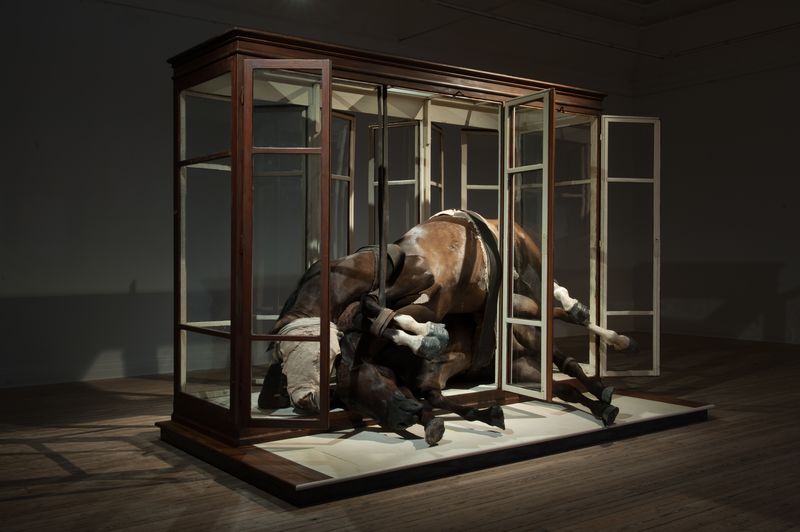

Subjects of animality, and equine imagery in particular, have occupied a central role in De Bruyckere’s oeuvre since 1999, when the Flanders Fields Museum invited her to create a work addressing the subject of war. Mining the museum’s archives, she discovered hundreds of photographs depicting the battle fields of World War I. In these photos, the cavalry horse transpired as a symbol of metamorphosis and the immensity of death, destruction and incalculable loss. At Hauser & Wirth, ‘No Life Lost II, 2015’ (2015) presents us with the bodies of three horses intertwined, lying atop one another and bound with leather straps in a glass vitrine. Exposed in death, De Bruyckere’s fallen creatures nevertheless offer up an indelible image of sublime beauty and dignity. Here the comforting element of a blanket appears; it is a cushion against force.

In the large gallery space, visitors will also find De Bruyckere’s ‘to Zurbaran, 2015’ (2015), a sculpture that refers to Spanish Baroque painter Francisco de Zurbarán’s depiction of the ‘Lamb of God’ (1635 – 1640). Conceived during the onset of the current Syrian refugee crisis, this sculpture presents a young, blindfolded foal laid upon a table with its legs trussed for the slaughter, an image that alludes not only to de Zurbarán’s iconographic lamb, symbolizing Christ’s sacrificial death, but also to the bodies of refugees who have met a tragic fate in the Mediterranean. The small foal’s vulnerable form rests gently upon a burlap blanket with a piece of cloth draped over its face – a blindfold that suggests powerlessness but also offers relief and protection in a moment of affliction.

De Bruyckere has long employed horsehides in her sculptural work, but it was only in 2014 that she first visited a skin trader’s workshop in Anderlecht, Belgium. This experience has strongly influenced her work ever since and is made particularly tangible in ‘No Life Lost I, 2014 – 2015’ (2014 – 2015) an installation comprised of three rows of hanging skins cast from wax and secured onto iron beams. Of this tribute to the rituals of the tannery, De Bruyckere recalls: ‘Maybe it was the amount of available skins, neatly stacked on iron pallets, or the smell of freshly slaughtered animals, the salt on the ground mingling with blood into a wet slush... I still don’t know, but I saw powerful images. I was unable to avert my eyes... I knew I had witnessed something I needed to transcribe. Never have I experienced death and life as intensely as I did there.’

Also on view at Hauser & Wirth is work from the series Penthesilea, 2014 – 2015, titled in reference to the opera, after a libretto by Heinrich Von Kleist. Drawing from Greek mythology, Von Kleist’s story stages the confrontation between Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons, and the warrior Achilles during the Trojan War. In a tragic tale of love, despair and madness, Penthesilea murders Achilles, not realizing that her lover had returned to surrender to her after all. Drawing inspiration from the vulnerability and strength of Von Kleist’s character, De Bruyckere confronts fragile skins of flesh-like wax – evoking the frail pink interiors of fresh hides, tenderly and sensually exposed – with tough, abrasive surfaces of iron and rust. The Penthesilea series sets up tensions between male and female energies, with a complex eroticism that both repels and attracts.

Moving through these works toward a final room of the exhibition, visitors are confronted by the cast of a thundering Burgundy elm, uprooted and sprawling nearly 60-feet along the concrete floor. Commanding the 5,000 square foot space, ‘Kreupelhout – Cripplewood, 2012 – 2013’ (2012 – 2013) is a monumental encaustic sculpture first presented in the silenced darkness of the Belgian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. It abstracts the gnarled and knotted body of a great fallen tree, wounded and scarred, its bark is flayed open, built up in layers and pigmented in a fleshy palette of wax. Conjuring a vivid likeness to tendons, bones and human flesh, this twisted trunk personifies the exquisite vigor, strength and suffering of Saint Sebastian, the venerated Catholic Saint and heavenly protector of the city of Venice against the deadly epidemics of the plague. In the body of the tree trunk, Sebastian appears: twisted branches metamorphosize into arms and legs entangled with crimson-soaked bandages and white tattered cloths. In the half-light of the room, the visitor comes face to face with an embodiment of beauty, mystical pain, and the power of transformation.