William Kentridge

Weigh All Tears

17 March – 29 May 2022

Hong Kong

In work made over the past five decades, William Kentridge has parsed and questioned the historical record—responding to the past as it ineluctably shapes our present—and in doing so, has created a world that mirrors and shadows our own.

Explore the exhibition with an introduction from William Kentridge

Through film, performance, theatre, drawing, sculpture, painting, and printmaking, Kentridge seeks to make sense of the world and the construction of meaning; his work brings viewers into awareness of how they see the world and navigate their way to more conscious seeing and knowing. Now on view, Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong presents ‘William Kentridge. Weigh All Tears’, an exhibition organized working closely with Goodman Gallery. This is Kentridge’s first solo exhibition in Hong Kong, and the first project between Hauser & Wirth and this Johannesburg-based artist.

The exhibition takes its title from a new 6-metre-wide triptych of the same name, where silhouetted figures form a procession against a collage of maps of Africa and archival documents. ‘Weigh All Tears’ is a phrase that cycles through Kentridge’s work, one of an evolving miscellany of phrases that recur in his work. They are ‘unsolved riddles, phrases which hover at the edge of making sense…. fragments of sentences which sit in a drawer of phrases used in other work over the years. On occasion they get taken out and sorted through.’

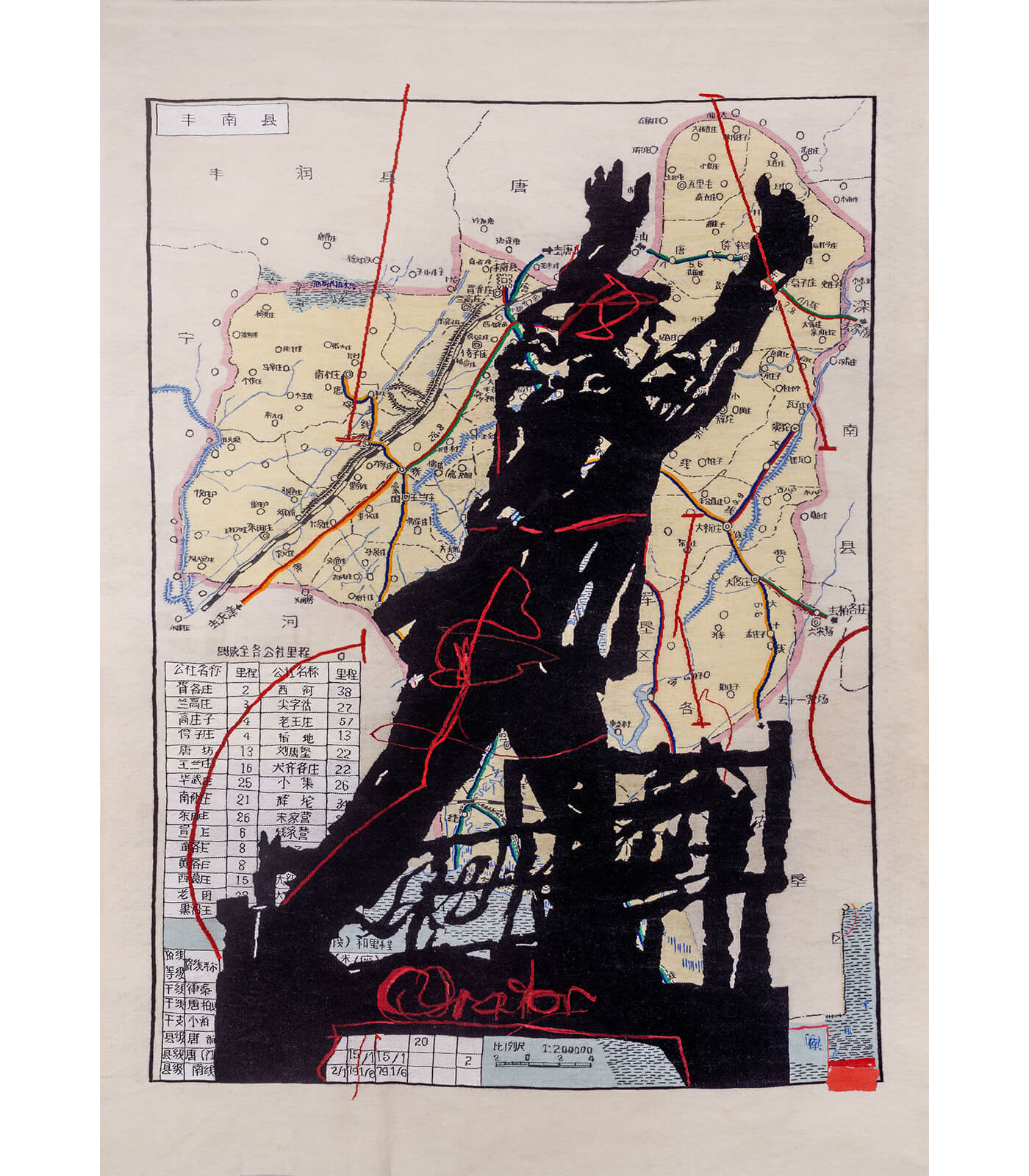

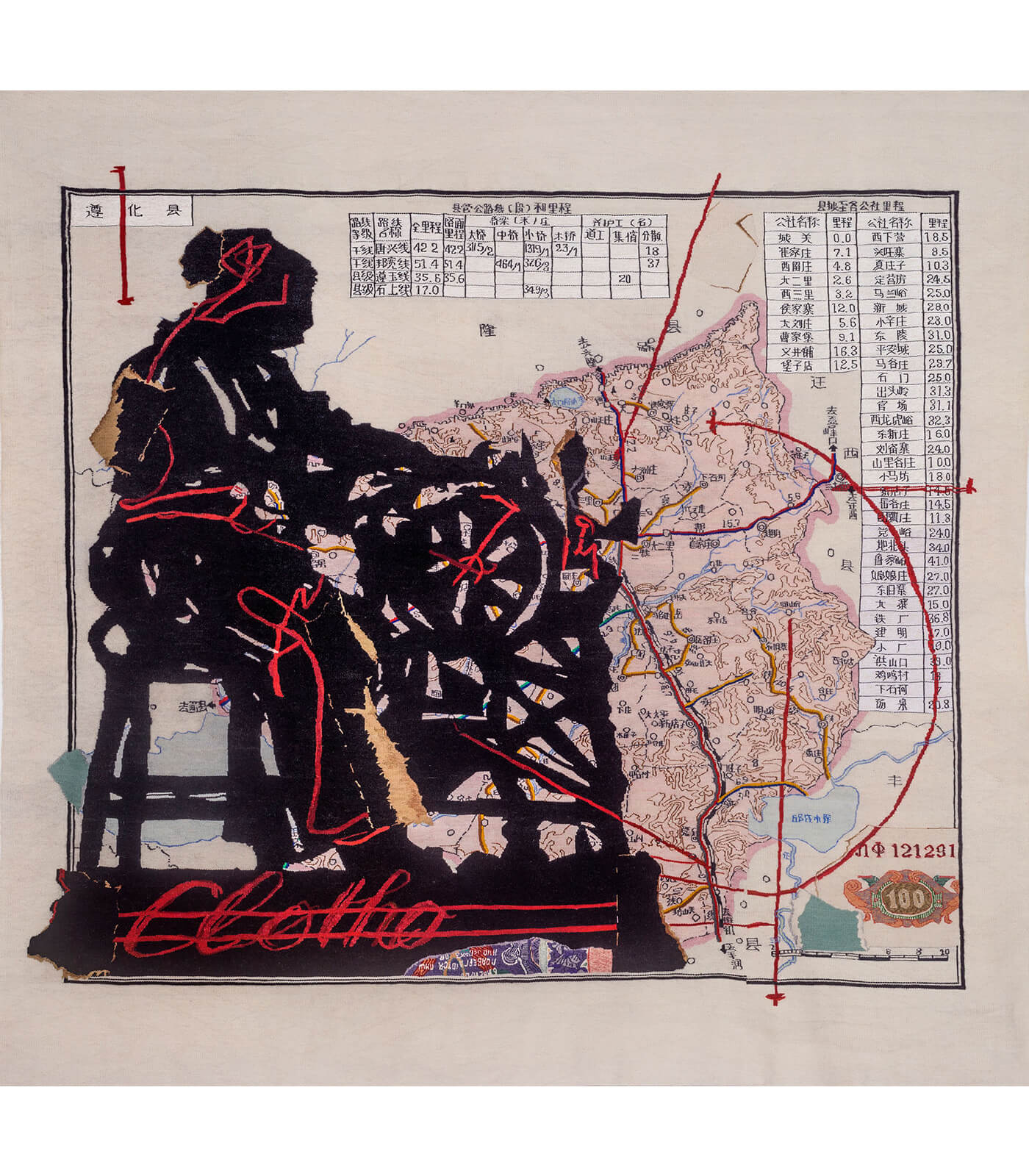

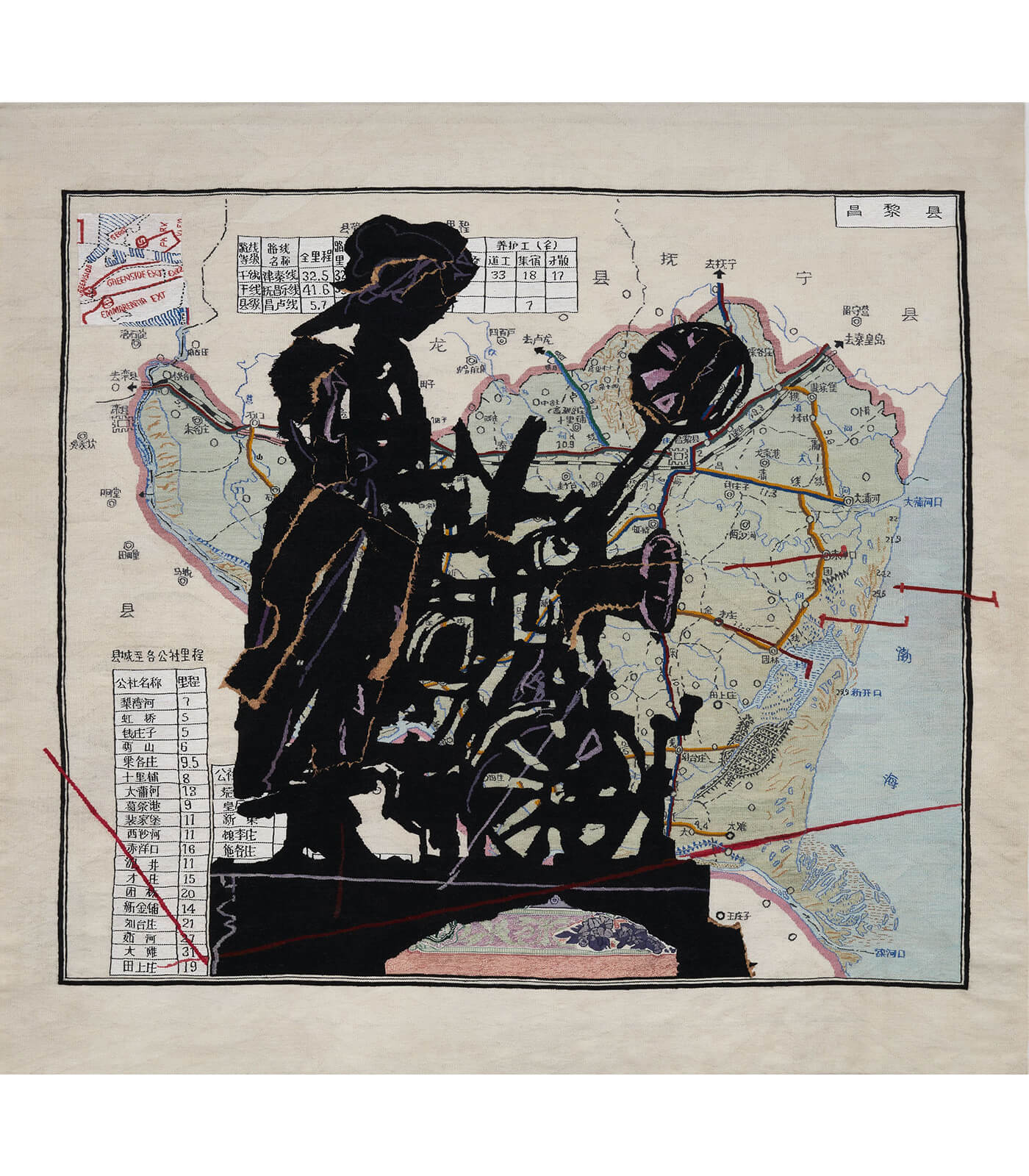

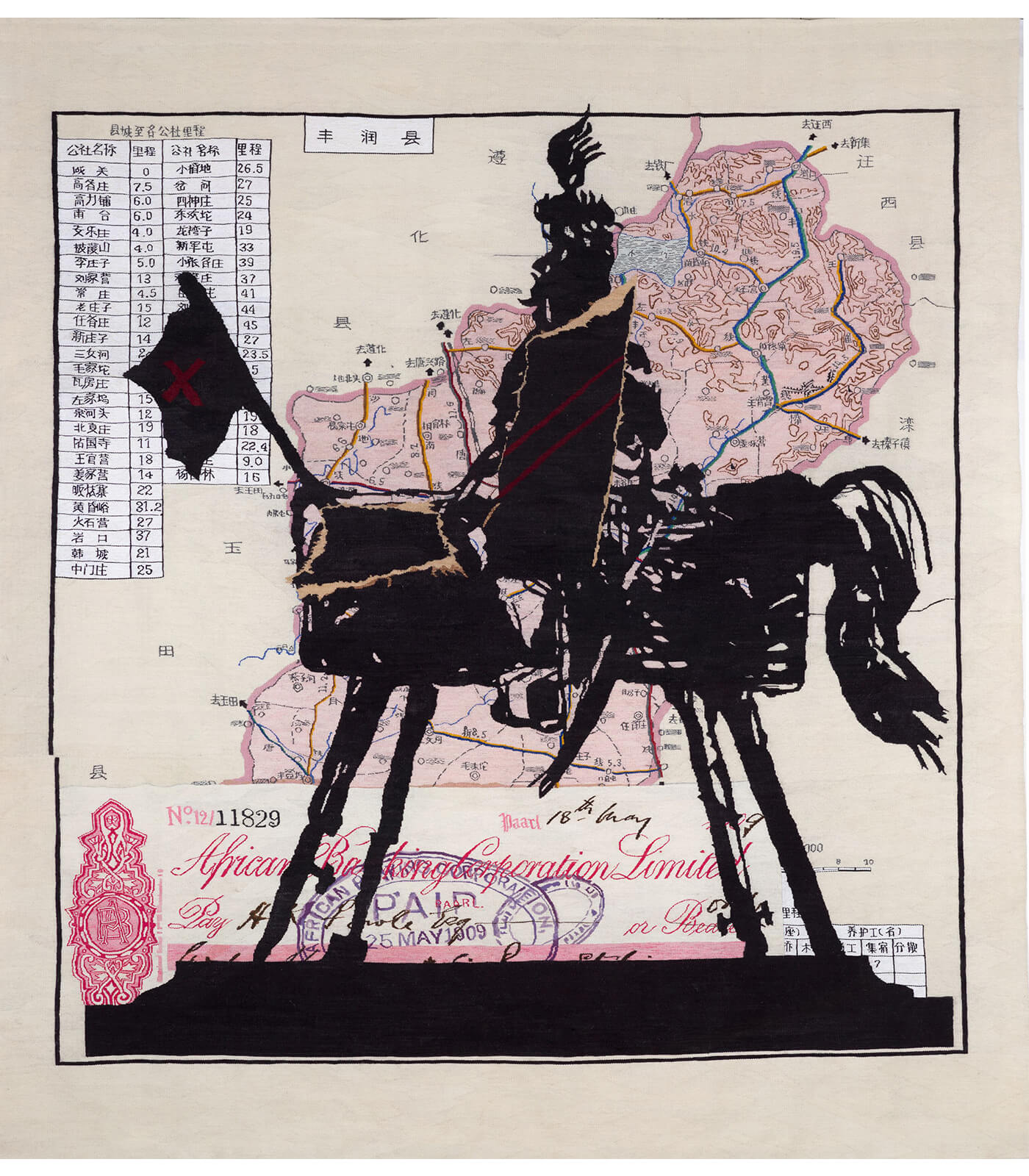

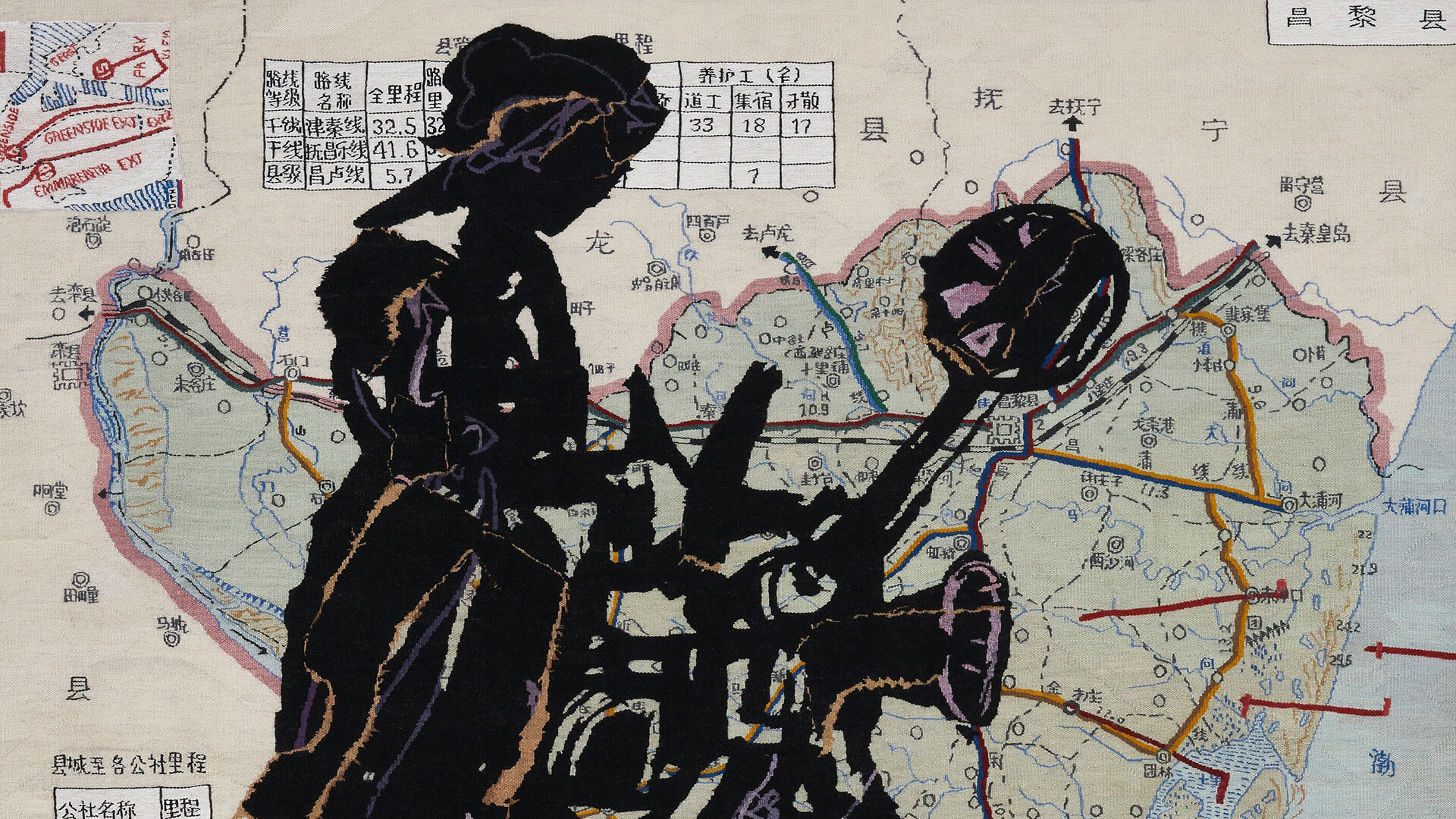

The figures in the triptych, like the phrases across different works, can be seen in four new tapestries in the exhibition: ‘Orator’ (2021), ‘Spinner’ (2021), ‘Mechanic’ (2020), and ‘Colleoni’ (2020). Since 2001, Kentridge has collaborated with Marguerite Stephens and her weaving studio outside Johannesburg, to translate the artist’s designs into hand-woven mohair tapestries. In the current series of tapestries, laser-cut silhouettes stand against backdrops of a Chinese political roadmap of the Hebei Province (ca. 1950-1970). The artist bought the Chinese maps seen here 20 years ago, waiting for the right moment and conjunction of images to present themselves, inviting their use. The tapestries create a space of multiple times and places, a space of inquiry and doubt: the era of the 1950s-1970s Chinese county map and the outlined figures, sometimes overlaid with colored marks and vestiges of collage technique.

The figure in the tapestry ‘Colleoni’ (2020), Bartolomeo Colleoni, was a mercenary and Captain General of Venice in the 1400s, depicted in a similar way as the Qianlong Emperor was painted by the Italian artist Castiglione in the 1700s. The figure on horseback recurs in Kentridge’s work, materializing his reflection on the heroics of men made resplendent by putting them on horses and elevating the horses on pedestals; and the subsequent disintegration, decay or destruction of those monumental figures. Here the horse is constructed from disparate elements and throws the heroic nature of such figures in question.

Through bricolage of wooden elements (including ladder legs), ‘Ladder Horse’ (2021) explores reduction of form and presents us with another horse of doubtful heroism.

Similarly, the three laser cut steel heads, ‘Revolutionary I’, ‘Revolutionary II’ and ‘Revolutionary (There Was No Epiphany)’ (all 2016) show a progressive ideogramic progression of a head taken from a model opera poster, with the last iteration incorporating text. The model operas of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) reworked the form of the Peking operas with revolutionary stories.

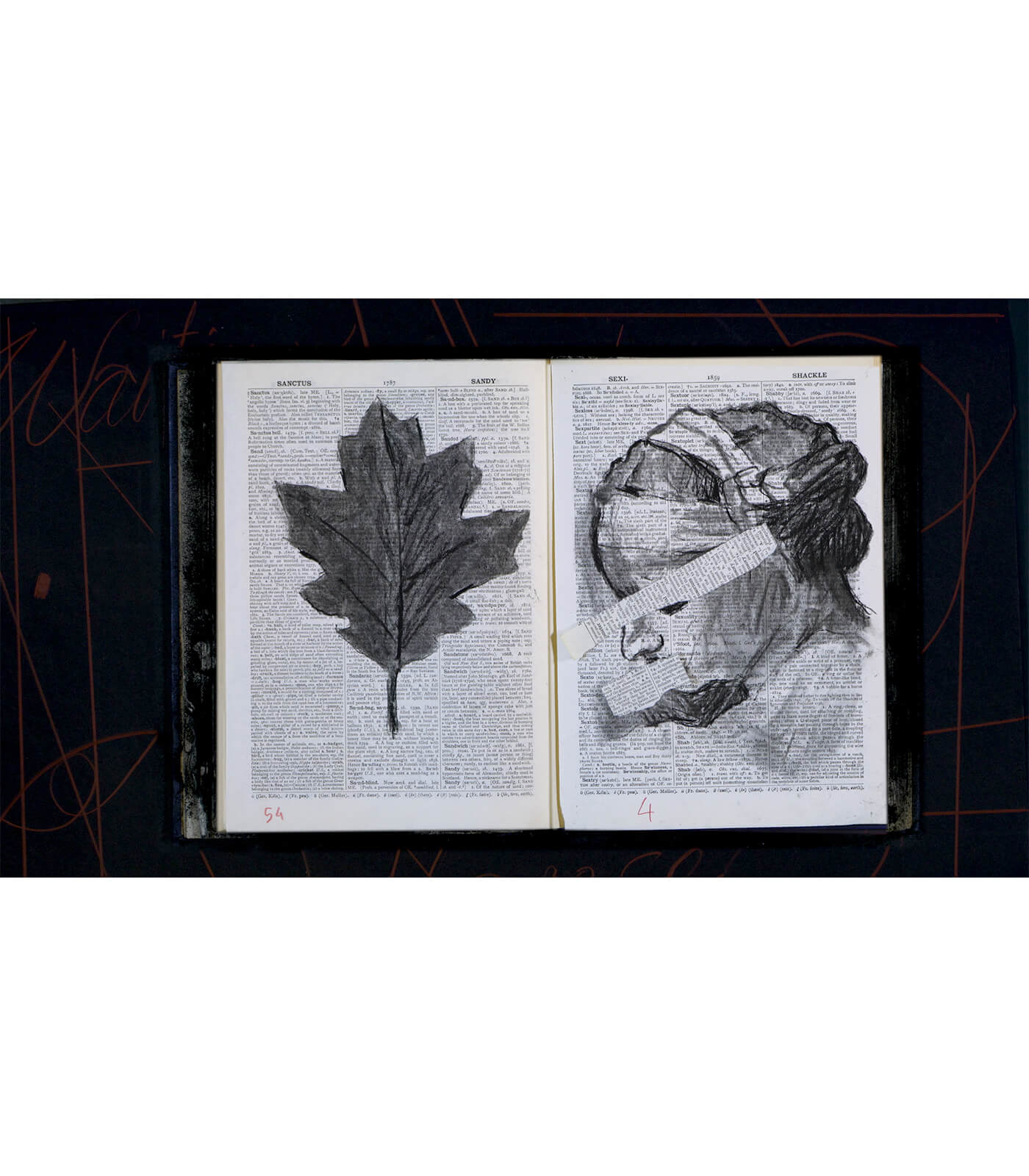

Also on view in the exhibition are a series of bronzes made in 2021 and cast at Workhorse Foundry in Johannesburg. A number of the sculptures are larger iterations of figures from the series of 40 small bronzes titled ‘Cursive’ (2020). Collectively the glyphs begin to read as a three-dimensional lexicon for the artist’s practice. The images started as a series of ink drawings and paper cut-outs on single dictionary pages.

Kentridge experimented with the visual language of glyphs and symbols transformed into sculpture, then played with their arrangement on shelves and in procession. Arranged in different sequences, the works read differently. A group of seven bronzes at larger scale is one configuration of possible meanings and associations. For Kentridge the glyph bronzes and the connections between them could be seen as a kind of self-portrait. ‘As if one definition of ourselves is the mass of associations with which we are filled, all of them waiting to latch onto the world and its objects as they come towards us.’

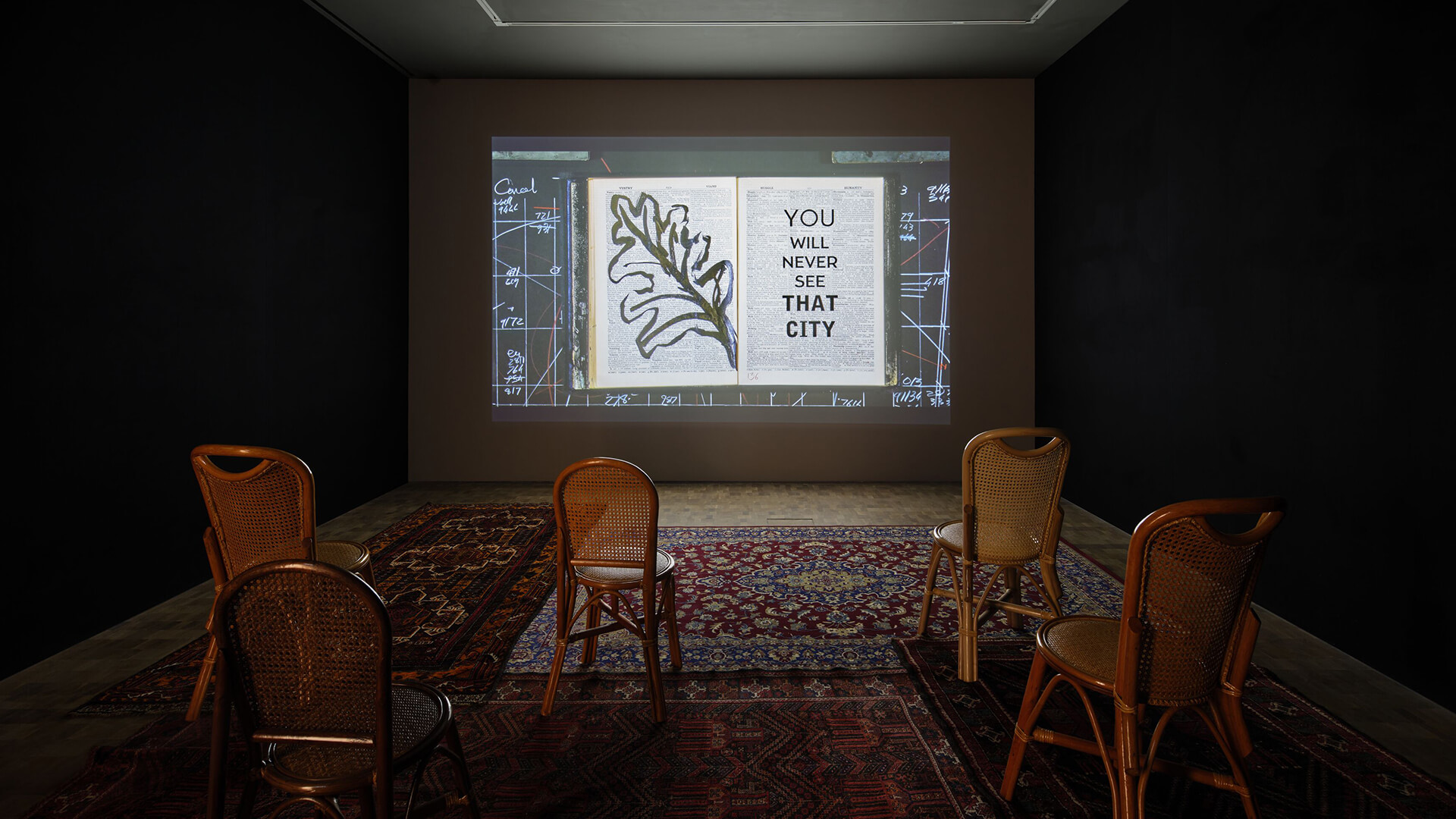

Finally, the 2020 film ‘Sibyl’ – which arises out of his 2019 opera ‘Waiting for the Sibyl’, commissioned by the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma and made in collaboration with composers Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd – brings together many of the figures, symbols and phrases found within the exhibition, which are seen within the flickering flipbook to a haunting soundtrack. The worker figures reappear in cyanotype blue paint. Drawn leaves appear along with drawings of trees, the figure of the dancing Sibyl, pages of effaced text, household objects, and abstract shapes.

Inspired by the myth of the Cumaean Sibyl – who would answer people’s questions about their destiny on oak leaves, which, however, inevitably blew in the wind and became confused – the film and its turning pages and transforming images are a reflection on fate and mortality. Kentridge has said, ‘Hovering over the piece is the awareness that our contemporary Sibyl is the algorithm, which knows us and our destinies better than we do.’

On view in Hong Kong

The gallery is open to the public Tue – Sat, 11 am – 7 pm. Please visit our location page to learn more.

About the Artist

William Kentridge

William Kentridge is internationally acclaimed for his artworks, theater and opera productions. His method combines drawing and erasing, tearing, gestural painting, collage, weaving, casting, writing, film, performance, music, theater and collaborative practices to create works of art that are grounded in politics, science, literature and history, yet maintain a space for contradiction and uncertainty.

Born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he currently lives and works, Kentridge grew up under the pall of apartheid. His practice has parsed and questioned the historical record—responding to the past as it ineluctably shapes the present—and created a world within his art that both mirrors and shadows the inequities and absurdities of our own. By employing varied mediums, Kentridge seeks to construct meaning through the use of historical resources, including maps, language and everyday imagery, while always maintaining a space for contradiction and uncertainty.

Kentridge’s work has been seen in museums and galleries around the world since his first survey exhibition in 1998 at Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels, including the Albertina Museum (Vienna), Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea (Turin), Johannesburg Art Gallery, Kunstmuseum Basel, Louisiana Museum (Humlebaek), Musée du Louvre (Paris), Museum of Modern Art (New York), Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid), Norval Foundation (Cape Town), Royal Academy of Arts (London), Whitechapel Gallery (London) and Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Cape Town). He has participated a number of times in documenta (Kassel) (2012, 2002, 1997) and the Venice Biennale (2015, 2013, 2005, 1999), as well as the Sydney Biennale (2008) and the Istanbul Biennale (1995, 2015).

Kentridge’s opera productions began in 2005 with Mozart’s ‘The Magic Flute,’ which embarked on an international tour of opera houses after opening at La Monnaie in Brussels, Belgium. Subsequent productions include Shostakovich’s ‘The Nose’ and Alban Berg’s operas ‘Lulu’ and ‘Wozzeck,’ and have been seen at opera houses including the Metropolitan Opera (New York), La Scala (Milan), English National Opera (London), Opera de Lyon, Amsterdam Opera, the Sydney Opera House, as well as the KUNSTENFESTIVALDESARTS (Brussels) and the Salzburger Festspiele. Kentridge’s film, ‘Oh To Believe in Another World,’ made to accompany the performance of Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony, premiered at KKL Luzern in 2022 and has since been performed in theaters and at festivals worldwide.

Kentridge’s theatrical productions, performed in theatres and at festivals across the globe, include ‘Waiting for the Sibyl’ (2019), ‘The Head & the Load’ (2018), ‘Ursonate’ (2017), ‘Winterreise’ (2014), ‘Paper Music’ (2014), ‘Refuse the Hour’ (2011) and, in collaboration with the Handspring Puppet Company, ‘Il Ritorno d’Ulisse’ (1998), ‘Ubu & the Truth Commission’ (1997), ‘Faustus in Africa!’ (1995) and ‘Woyzeck on the Highveld’ (1992).

In 2016, Kentridge founded the Centre for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg: a space for responsive thinking and making through experimental, collaborative and cross-disciplinary arts practices. The center hosts an ongoing program of workshops, public performances and mentorship activities.

Kentridge is the recipient of honorary doctorates from several universities including Yale, University of London and Columbia University. In 2010, he received the Kyoto Prize. In 2012, he was awarded the Commandeur dans l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France and he presented the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University. In 2015, he was appointed an Honorary Academician of the Royal Academy in London. In 2017, he received the Princesa de Asturias Award for the arts and, in 2018, the Antonio Feltrinelli International Prize. In 2019, he received the Praemium Imperiale award in painting in Tokyo. In 2021, he was made a Foreign Associate Member to the French Académie des Beaux Arts, Paris. In 2022, he was presented the Ordine della Stella d’Italia and, in 2023, he received the Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in Opera in London. As the Slade Professor of Fine Art for 2023/2024, Kentridge delivered a series of six lectures at the University of Oxford in January and February 2024.

His work can be found in the collections of public and private museums including Amorepacific Museum of Art (Seoul), Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth), Art Institute of Chicago, Broad Art Foundation (Los Angeles), Carnegie Museum of Art (Pittsburgh), Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea (Turin), Centre Pompidou (Paris), Fondation Cartier (Paris), Fondation Louis Vuitton (Paris), Fundaçion Sorigue (Lerida), Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Haus der Kunst (Munich), ICA Boston, Israel Museum (Jerusalem), JAG (Johannesburg), Kunsthalle Mannheim, Kunsthalle Praha (Prague), Kunstmuseum Basel, LACMA (Los Angeles), Louisiana Museum (Humlebaek), Luma Foundation (Arles), MAC (Montreal), MAXXI (Rome), Moderna Museet (Stockholm), MoCA (Los Angeles), MUDAM (Luxembourg), MoMA (New York), Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest), National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), National Museum of Modern Art (Kyoto), National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne), Norval Foundation (Cape Town), San Diego Museum of Art, SFMoMA (San Francisco), Sharjah Art Foundation, Sifang Art Museum (Nanjing), Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), Tate (London), Vehbi Koç Foundation (Istanbul) and Zeitz MOCAA (Cape Town), as well as private collections worldwide.

Inquire about available works by William Kentridge

The gallery is open to the public Tue – Sat, 11 am – 7 pm. Please visit our location page to learn more.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10