Conversations

A Kaleidoscopic Unpacking

Artists Rashid Johnson, Tiona Nekkia McClodden and Taryn Simon on the work of Leon Golub (1922–2004) and addressing dynamics of power

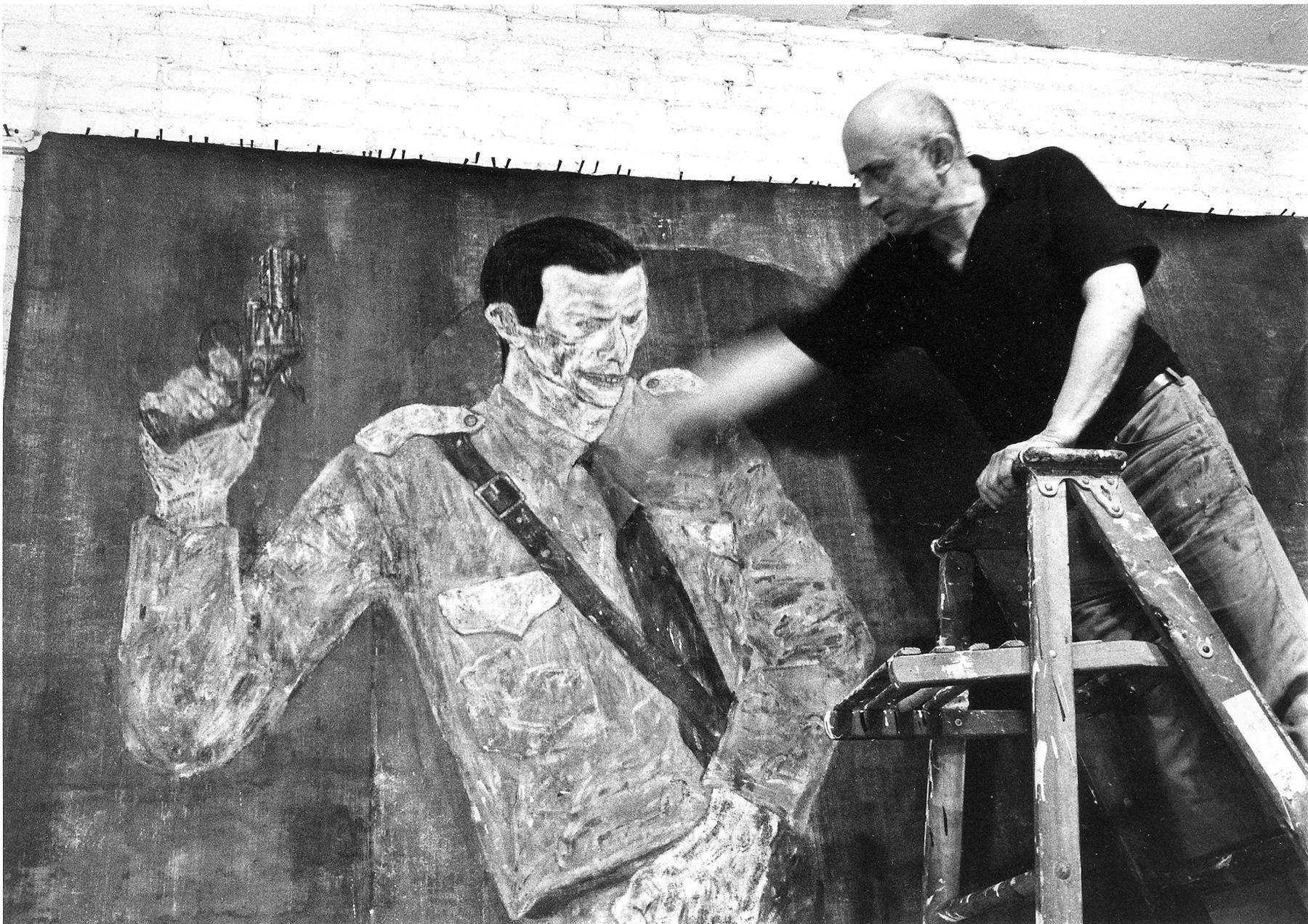

Leon Golub, Mercenaries IV, 1980. Photo: Thomas Barratt

The group exhibition “Et In Arcadia Ego,” conceived by artist Rashid Johnson and currently on view at Hauser & Wirth New York’s 22nd Street location, takes the paintings of American artist Leon Golub (1922–2004) and places them in dialogue with works by ten international artists that spans from the postwar period to present day. Johnson first encountered Golub’s work on an early school trip to the Art Institute of Chicago and later as a graduate student at the Art Institute, where Golub had also studied in the 1950s.

In this exhibition, Johnson aims to reframe Golub, who is often categorized as political or activist artist, in a broader context that includes not only his interest in the blunt force of power but also at the uncertainties and vulnerabilities that stem from conflict. Artists in the exhibition include Philip Guston, David Hammons, Wifredo Lam, Sharon Lockhart, Robert Longo, Teresa Margolles, Tiona Nekkia McClodden, Taryn Simon and Johnson himself.

On October 5, Kate Fowle, senior curatorial director at Hauser & Wirth, sat down with Johnson, McClodden and Simon to talk about why Golub’s aesthetic and thematic interests resonate with the group as working artists. These are condensed and edited portions of their conversation.

Kate Fowle: I want to start with asking Rashid about how this exhibition came together. Could you explain a little bit about why you curated a show around Leon Golub now?

Rashid Johnson: I grew up in Chicago, and when I was young, Golub seemed like the most famous artist I'd ever come across. He had gone to school at The Art Institute of Chicago, and I first saw his work around age seven or eight on a school visit there. I remember that the amount of space that Golub's work occupied on the walls was more significant than that of Picasso. His footprint stayed enormous through my time as a graduate student at the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 2000s, about fifty years after he studied there. My assumption was that Golub was a humongous figure in the history of art. And I think that he actually is, though maybe to a lesser extent than I thought back then.

The question I’ve been asking myself now is: Why am I not seeing his work more? Because it’s filled with a level of transgression and radical gestures that shows a prescient understanding of the complexity of the human condition. So, to answer your question, I took on the task of taking work of a hero of mine—an artist that I see as essential to my practice and other artists' practices. I approached the exhibition as an opportunity to reflect on themes that matter to me and to use those reflections as a kind of philosophical launching pad.

KF: It's quite an unusual response because people who know Golub’s work might expect the show to go in a political direction, but you are thinking about Golub in a much broader way—as you described it, a “kaleidoscopic unpacking.”

Leon Golub in his studio, circa 1984. Photo: David Reynolds

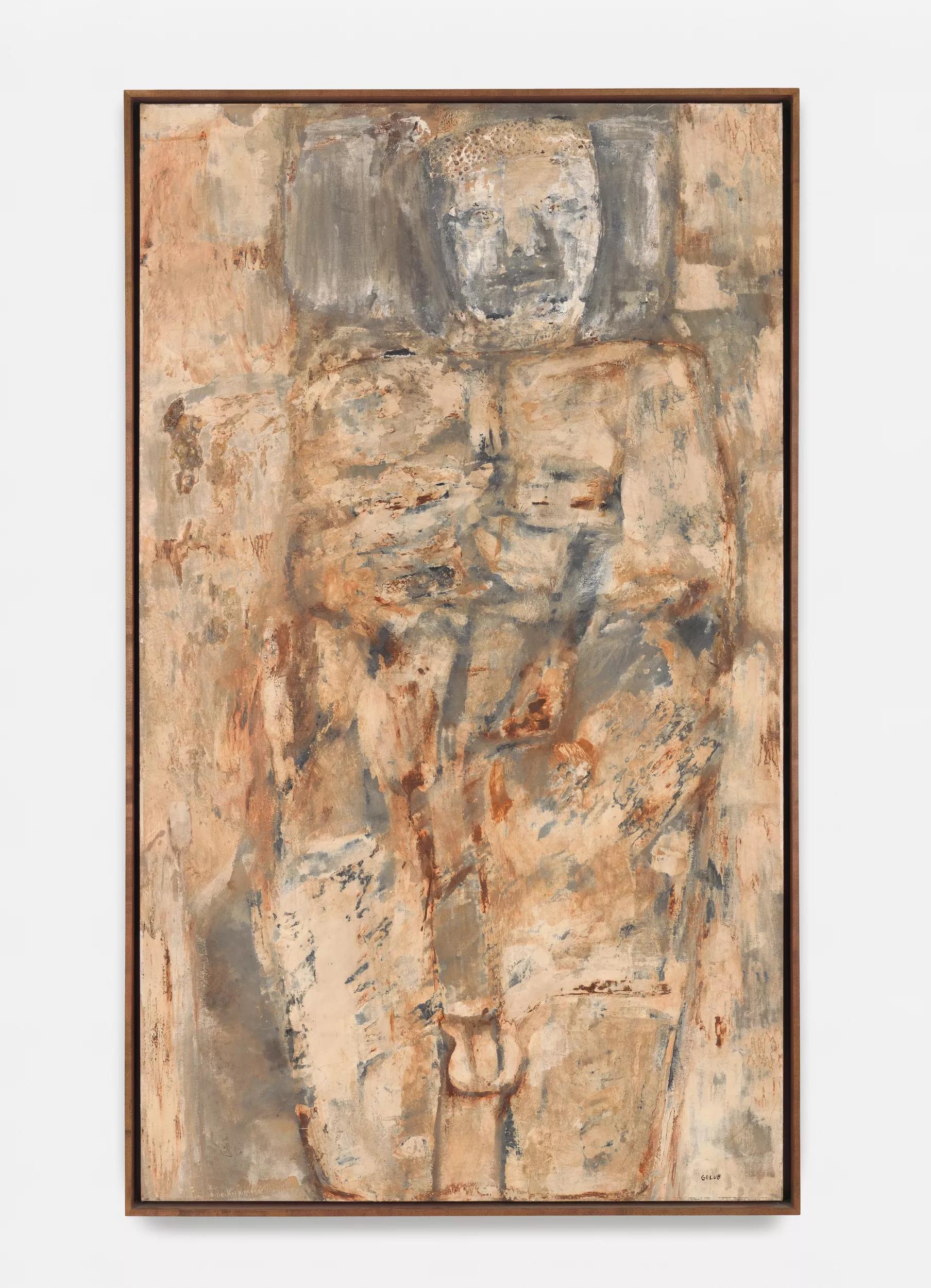

Leon Golub, Philosopher IV, 1958. Photo: Alex Delfanne

“We would be doing Golub an enormous disservice if all we discussed was the activist position that we assume the work takes. There are so many different aspects to his painting.”—Rashid Johnson

RJ: Without question Golub’s work challenges the idea of power dynamics. A recurring question in it is: Who holds the power in the picture? And Threnady I (1986) is a great example of that.

One of the aspects of his work that I'm very interested in is his willingness to give agency to people outside of his own experience. It's rare in the Western tradition for a white, cis male painter to show people outside of that identity without inherently depicting himself in a position of power over those people.

But we would be doing Golub an enormous disservice if all we discussed was the activist position that we assume the work takes. There are so many different aspects to his painting. I’ve never seen it singularly—I look at the way that he goes about picture-making with scale and with the relationship his work has to historical painting, the way he employs space and allows for the agency of unprimed canvas in certain works. I’m interested in his use of collage, made with imagery from his personal archive of photos, which includes everything from gay porn to cutout hands of models from Vogue magazine.

KF: And as soon as we started discussing the show, you knew you wanted to include Taryn and Tiona, for very different reasons?

RJ: Yes. I knew Tiona’s work about masking and unmasking, and that really excited me for this show.

KF: Tiona, could you say a little bit about that?

TNM: Yeah. I have two masks in the show, and the one titled If you had ever thought that you saw me, let me assure you that you have not seen me as I know myself because I have not found you worthy of this image is an exploration of thinking about the mask as something that conceals but also reveals at the same time. I have ASD, so I confront a lot of aspects of internalized ableism as someone who deals with a disability that's invisible. Masking is something that I think a lot of people do in general ... It's like the thing that hovers above you when you step out of your house, to help you navigate your day in certain spaces. There are also very interesting intersections of that thought with African masks and many different kinds of powerful masks, war masks. I think about gimp masks too, not only in the sense of sadomasochism, but looking at a gimp mask and thinking about how it has figured throughout various cultures as a marker of a person who is intellectually challenged or disabled. At the same time it’s connected to pleasure, and it’s a marker of a space in which someone wants to be used. Gimps are very interesting to me, specifically because they are basically there to provide a projection of your own desire or use value. In the space of SM or BDSM, when you put on a mask, it's to erase your identity so that you can become whatever the person you serve wants you to be.

RJ: If you think about Leon's work and masking and hooding in different ways, Tiona’s work makes so much sense in that conversation.

KF: And Taryn’s work brings to the exhibition questions of reportage or witnessing.

RJ: Right. One of the things that Taryn's work does so successfully is bear witness. Her work has a willingness to not avert its eyes and to take on really challenging subjects. She was an artist that I thought of early in the process to include.

Taryn Simon: Thanks for that, Rashid.

“Masking is something that I think a lot of people do in general ... It's like the thing that hovers above you when you step out of your house, to help you navigate your day in certain spaces.”—Tiona Nekkia McClodden

KF: Taryn, do you want to say a little bit about your work in this context?

TS: It’s a work which came out of a prior project of mine, The Innocents (2000–2003), which focused on documenting the stories of people who had served time in prison for violent crimes that they didn’t commit. I was looking at photography's role in that process and how it led to imprecise memory in eyewitness identifications, which in turn led to incredible pain and suffering and fictions. Around that time, the film director Brian de Palma became aware of my project and asked me to do a photograph for the final frame of a film he was working on, titled Redacted (2007). That film was also about photography and documentation, but it was about the absence of photographs, particularly in the war happening in Iraq, and how a lack of distributed images of the violence occurring there could affect global ideas around the war. This photograph that’s the basis of the work, Zahra/Farah (2007) shows the Iraqi actress Zahra Alzubaidi in Jordan on the film set. In the years since, the photograph has morphed and taken on new, unexpected meanings, as distribution of it has had an impact on both the retelling of what happened to the person Zahra portrayed in the film—Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi, a fourteen-year-old Iraqi girl who was raped and murdered by U.S. soldiers in Mahmudiyah, Iraq in 2006—and Zahra herself, who received death threats for her participation in the film and sought political asylum in the United States, becoming a U.S. citizen in 2017.

Within that, it's also important to note that photographs give very narrow context as well as specific views of a history. The photograph and its accompanying texts in this work doesn't fully capture Zahra's story and what preceded that or what comes after. That's the difficulty of photography and of making any artwork that deals with political content, or any content for that matter.

Leon Golub, Threnady I, 1986. Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer

“It’s also important to note that photographs give very narrow context as well as specific views of a history.”—Taryn Simon

KF: Those points make me think about Golub and the content found in his work. He got his art history degree in 1942 and then he was a cartographer in the Second World War based in different places around in Europe. He graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1950—the same place where Rashid graduated from in 2005—and his work moves from a kind of interiority in the 1950s to taking on painting matters of vast concerns. He’s thinking through the Holocaust and also Vietnam. These are paintings of wars and specific moments, yet with the backgrounds compositionally there’s nothing there. So when we look at these works, they're kind of timeless. We can see something in these works now that resonates with us right this second. Does this kind of timelessness matter to your practice, or does it not at all?

RJ: It’s interesting to think about because the show starts with Golub's work from the 1950s, which has an existential journey attached to it. He transitions from the idea of interiority or the existential to the exploration of the human condition to an actual recognition of bodies being covered in napalm and being burned, which we see in his paintings about Vietnam. There are other experiences that Golub depicts that show us what we imagine to be from the real world, but it's all put together via an archive of images. None of these things actually ever literally took place, but they still then carry that same existential concern.

This idea that an artist is never living in permanence is for me the most interesting thing, that at any given time that process can evolve and they can change. They can show us something vastly different about them exactly than we expected previous of them. Maybe in some ways that’s what makes it so exciting to watch an artist’s practice, that one day they might wake up and do something that you never expected them to do. The journey of that timeless experience or those timeless pictures tells something much more complicated than I think is easily translated.

A video recording of the entire conversation can be viewed here [link forthcoming].

–

Rashid Johnson is among an influential cadre of contemporary American artists whose work employs a wide range of media to explore themes of art history, individual and shared cultural identities, personal narratives, literature, philosophy, materiality, and critical history. Johnson received a BA in Photography from Columbia College in Chicago and studied for his masters at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Johnson's work is known for its narrative embedding of a pointed range of everyday materials and objects, often associated with his childhood and frequently referencing aspects of history and cultural identity. His more recent works delve into existential themes such as personal and collective anxiety, interiority and liminal space.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden takes an interdisciplinary approach as a visual artist, filmmaker and curator to interrogate ideas of ritual and order through its relationship to identity and the conditions of being human. Traversing documentary film, experimental video, sculpture, sound installation and poetry, her practice explores themes of Black interiority, biomythography and queer poetics.

Taryn Simon directs our attention to the unseen forces shaping the worlds we inhabit. Her projects, using photography, sculpture, text, sound and performance, center on storytelling, secrecy and the hidden contours of power and authority. Her multi-year projects are informed by research with varied institutions such as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the International Commission on Missing Persons, the Fine Arts Commission of the CIA, Playboy Enterprises and the New York Public Library.

Kate Fowle is Curatorial Senior Director at Hauser & Wirth. Previously, she has served as director of MoMA PS1, chief curator and artistic director of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow and executive director of the New York-based Independent Curators International.

“Et In Arcadia Ego” is on view at Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street from September 5 through October 19, 2024.