Conversations

Sophie Taeuber-Arp & Hans Arp: Cooperations—Collaborations

On the occasion of a new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Publishers HQ, book collector Daniel Segmüller in conversation with Stefan Zweifel and Michaela Unterdörfer

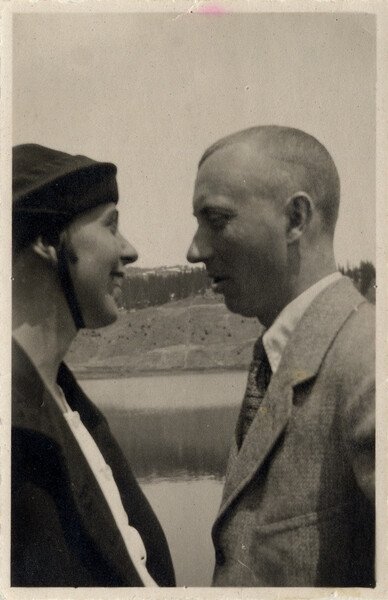

Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hans Arp, Arosa, 1918 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth. Courtesy Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth and Hauser & Wirth

The making of books is most often a collaborative effort: someone to write, to edit, to design, to print, to publish—each of these facets often engaging more than one point of view. Such collaboration was at the heart of Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hans Arp’s artistic practice, which thrived on the exchange of ideas between the couple and other artists, made manifest in book form. Today these books are material records of the brilliant work that came out of radical interwar art movements like Dadaism and Concretism.

Since the early 1980s, antiquarian book dealers Daniel Segmüller and Ruth Seiler have collected more than 300 publications on and by Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hans Arp, part of an extensive collection of artists’ books. A selection of these titles have been brought together for "Sophie Taeuber-Arp & Hans Arp: Cooperations—Collaborations," an exhibition of books and portfolios at the Hauser & Wirth Publishers bookshop and headquarters in Zurich on view 9 April – 26 June 2021. On the occasion of the presentation, Segmüller spoke with author and curator Stefan Zweifel and Hauser & Wirth Publishers director Michaela Unterdörfer about the collaborative relationship between Taeuber-Arp and Arp, and with their contemporaries.

Stefan Zweifel and Daniel Segmüller, Hauser & Wirth Publishers HQ, Zurich, February, 2021

Michaela Unterdörfer, Hauser & Wirth Publishers HQ, Zurich, February, 2021

Michaela Unterdörfer: Before we get to the individual art books and book artworks from your collection: were you primarily acting from the perspective of book collector or bookseller? Or how did these roles inform and inspire one other?

Daniel Segmüller: The adventure that led to the collection of the books in front of us began in a quite straightforward manner. Back in 1979 I co-founded a cooperative bookshop while studying German and theology in Fribourg. That’s how I became a bookseller. As part of a didactics exam, my wife Ruth Seiler—whom I met in Fribourg during my studies—and I had to give a German lesson to children in a special school, and we thought: these kids are having trouble reading and concentrating. And so we said, okay, let’s do phonetic, visual poetry with them. But during the preparations, we realized that the libraries in Fribourg didn’t have a single book with concrete or visual poetry. So we travelled all over Switzerland to antiquarian bookshops and collected our books. That’s how we became collectors. And in 1987, my wife and I founded our antiquarian bookshop in Lucerne. We were looking for a name that referenced both literature and art. That’s what made us think of Hans Arp, who we saw as a man of letters and an artist in equal measure, and so we named the antiquarian bookshop after one of his most famous poems: "Die Wolkenpumpe"–The Cloud Pump. An homage to Arp that alludes to our specialized areas of focus: literature and art of the 20th century.

Arp & Co Stefan Zweifel: We are sitting here surrounded by artists’ books that probe the diverse collaborations and cooperations of Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. They all revolve around the key phrase "Arp & Co." The most intimate "Co.," however, refers to the collaboration and coexistence of Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Their mutual Dadaist friend Marcel Janco once commented in retrospect that he always perceived the works of the two as a kind of collective oeuvre. Are their works as closely intertwined for you as well?

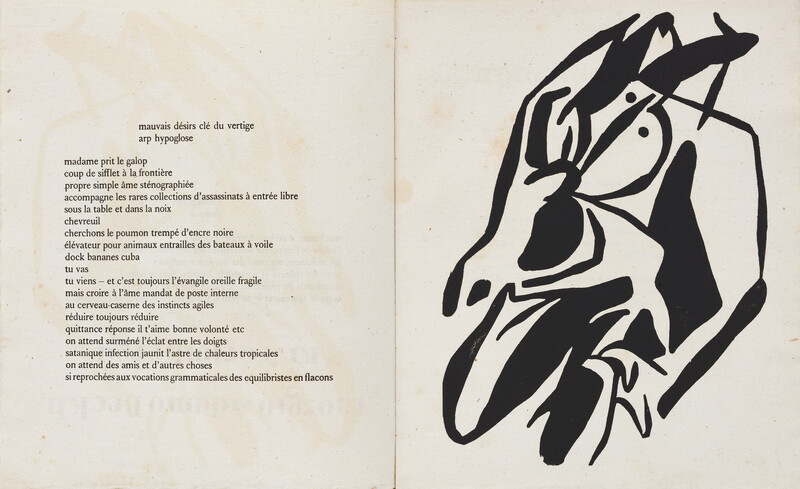

DS: Well, even at the very beginning of their acquaintance, when they met in 1915 at the Galerie Tanner in Zurich where Arp was exhibiting drawings, tapestries and embroideries with Otto van Rees and his wife, Adya, they started working together soon thereafter. And this is evidenced by the change in Arp’s art. If you look at how abstractly Sophie was already working at this time, you notice how symmetries and the play with horizontals and verticals come from textile design in her work. In weaving, you have to work with the horizontal and vertical structure of the threads. Strictly geometric and abstract. Arp, however, had produced quite different drawings in the period between 1912 and 1915. For example, these pen-and-ink drawings he made for an edition of the Bhagavad Gita, but also the pieces he exhibited at the Moderne Bund (Modern League)—these were figurative works! And then in 1916, you have these axially symmetrical woodcuts for the edition of Richard Huelsenbeck’s Phantastische Gebete (Fantastic Prayers)... Perhaps a clue that this was in fact a collaboration between Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber! In any case, it was the only book featuring such symmetrical works by Arp. He then moved on to amorphous forms—while Sophie continued to work with these horizontal, vertical structures for quite some time. So they presumably operated as a duo right from the start.

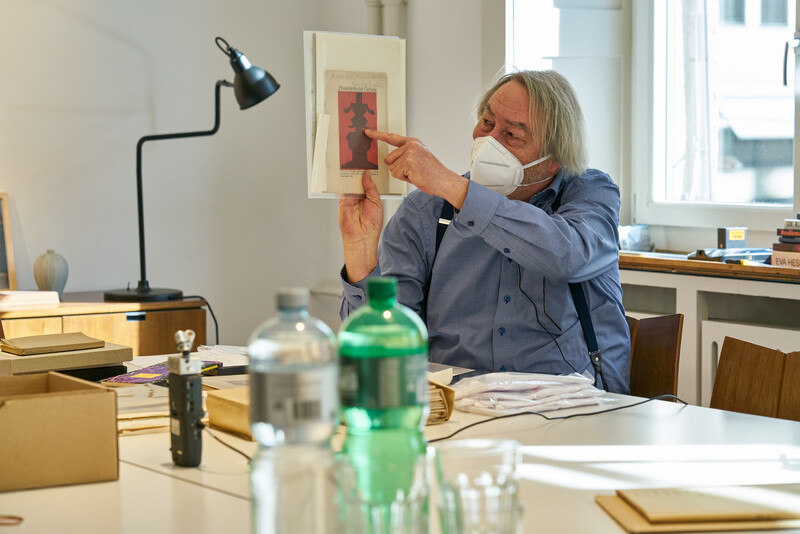

Daniel Segmüller holding a copy of Richard Huelsenbeck’s Phantastische Gebete (Fantastic Prayers), 1916, Hauser & Wirth Publishers HQ, Zurich, February 2021

Spread from Richard Huelsenbeck’s Phantastische Gebete (Fantastic Prayers) with one of seven woodcuts by Hans Arp, 1916 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich

SZ: That fit the collective spirit of Dadaism: while the individual nations were slaughtering each other on the battlefields, artists from all countries came together at Cabaret Voltaire to counter the mindset of technical reason that led to war, with unreasoned "non-sense." Like the individual nations, the individual personalities were to meld within a community where, as Arp said, "the hands are brothers"—not sisters, but at least brothers... This community of hands was particularly evident in the tapestries, where the hands of Arp and Adya van Rees intersected in a very real way.

DS: That brings us to the title of this exhibition: "Cooperations—Collaborations." Perhaps we can start with that. What were the different types of collaborations? What did they consist of? Arp wrote during the Dada era: "Works of art should remain anonymous in the great studio of Nature; just like clouds, mountains, seas, animals and men. Yes, men should return to Nature, artists should work in a confraternity like the artists of the Middle Ages." Arp was interested in the blurring of authorship. It was along these lines that he spoke of "namelessness" in art, as was the custom in medieval times. And what’s astonishing is that Arp already practiced this approach as a 19-year-old. In 1905, when he was just 19 years old, he painted a fresco, two by six meters, with his Alsatian art teacher Georges Ritleng in the Arp family’s country home in Alsace. Here, too, the authorship is blurred; it was a collaborative work, a collaboration between his teacher and himself. This continued when he painted two murals with van Rees for the Pestalozzi Schoolhouse in Zurich in 1915. There is a photograph of them both standing in front of the mural and painting. It is impossible to say which part was by van Rees and which by Arp. And to return to the innermost "Co." of "Arp & Co.": the "Duo-dessin" series by Arp and Sophie executed in 1939. There, too, you can only guess which lines and contours are by whom.

SZ: And Arp continued this collaboration with Sophie even after her death!

DS: Yes, Arp tore up the joint drawings after her death and reassembled them as a collage. I’m not sure how the authorship was then interpreted—if it went from being a duo or collaboration work to a genuine work by Arp. Of course, these are embedded in a large group of "papiers déchirés" for which Arp also tore out old material from his own books and pieced them together again in a collage format. I once visited the Dada collector Hans Bolliger and asked him, "Hans, tell me, why do Der Vogel Selbdritt and Cinéma calendrier, these two icons from Arp’s oeuvre and Dadaism, almost never appear on the market? Everything else periodically comes up for sale: all the issues of the magazine Dada or Tristan Tzara’s poems Vingt-cinq poèmes with Arp’s illustrations! Everything! Only these books, which had been printed in an edition of 150 copies, were nowhere to be found." Then Hans Bolliger explained that Arp tore up a good many of them up. And I can prove it—I can show you how he went about it: This is a woodcut from the Cinéma calendrier from 1920. Some twenty-five years later, Arp made a collage from it for Tzara’s Vingt-cinq-et-un poèmes. And here, as a third, is an independent papier déchiré—you can even see the torn edges. This is now hanging in the Tate Gallery. In other words, he already tore up two issues of Cinéma calendrier to make this subsequent collage and this papier déchiré.

MU: These books were mostly self-published...

DS: ... or like Max Ernst’s collages of Arp’s weisst du, schwarzt du published by the Pra-Verlag—PRA as in ARP!

Spread from Cinéma calendrier du coeur abstrait, Maisons (Cinema Calendar of the Abstract Heart, Houses), with poems by Tristan Tzara and 19 woodcuts by Hans Arp, 1920 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich

Daniel Segmüller holding a copy of a papier déchiré by Hans Arp, Hauser & Wirth Publishers HQ, Zurich, February 2021

MU: You can imagine that they had hardly sold and were lying around the studio in little stacks, waiting for buyers.

DS: Exactly. And that raises the question of why he only started with the papiers déchirés in the 1930s, for which he repurposed old publications. In this context, there was a triggering experience for Arp. After his mother passed away in 1929, he found his own old printed things in her house, stored in damp conditions and riddled with mold stains. And instead of throwing them away, he brought them back to life. In doing so, the processing of her death is fused with his desire to reincarnate everything. There are two photos of Arp from the late 1950s, early ’60s where he is eating paper. He chews old things and spits them out in a new form, as it were, shaped by chance. A profoundly Dadaist form of collaboration.

Hans Arp, Clamart, 1960 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth. Courtesy Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Heidi Meister

The cover of Der Vogel selbdritt (The Bird Thrice with Itself), with poems and six original woodcuts by Hans Arp, printed by Otto von Holten, 1920. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich

Collaborations

SZ: While the joint work with Sophie continued beyond her death in a manner of speaking, this spirit of collaboration dissipated. The final testimony to Arp’s collaborations and simultaneously their ultimate climax is certainly the Album Grasse—a compelling attestation from the darkest days of the Second World War.

DS: And yet Arp wrote that the collaboration and time spent with Alberto and Susi Magnelli as well as Sonia Delaunay after their flight from Meudon to the south of France in the middle of the war was the most wonderful period, this working together with colleagues. And it really gave them something that they would otherwise never have done in isolation. At the same time, they lived in utterly miserable conditions during these months in 1940–41—a period of great deprivation in Grasse. There is an anecdote describing how Sophie Taeuber made a cake with an egg, and it was served at tea, probably with Sonia Delaunay and the Magnellis. Arp harshly scolded Sophie, asking how she could think of wasting the last egg like that.

MU: Southern France was a place of emigration, and the portfolio is a telling contemporary historical document. The context of its creation strikingly reflects the tragic fates of these artist friends and their supporters.

DS: The idea was actually that this portfolio would be released in Grasse in 1942. Without mentioning the names of the artists, simply with the title Album Grasse, And they wanted to have it printed in Grasse, with ten lithographs. But the lithographer was taken away by the Gestapo and deported to a camp. Sonia Delaunay saved these originals and hid them away. After the war, she brought them to Paris where she had them printed in 1950, eight years later. And that had its consequences: I have had several copies of the Album Grasse in my hands. They are always marked with foxing stains because certain sheets were not allowed to dry properly, but simply printed "chop-chop."

SZ: And in the meantime, the character of the work has also changed significantly.

DS: Yes, exactly! Sonia Delaunay told the printers to print a kind of an answer key as the last sheet, where it records which sheet is by whom, which hands interacted on the respective sheet. That was not Arp’s intention. He really wanted it to be like in the Middle Ages: anonymous with the blurring of authorship. And it was not done that way. I would say that if you look at it now—and you don’t know who made which sheet—you can already guess to a certain degree. The artistic signature is actually very recognizable for all of them. Delaunay is clear, as are Arp and Sophie Taeuber. Only with Magnelli, you might think it could be Delaunay. But even without this last sheet with the answer key, I think you could probably figure out who worked on which sheet.

MU: It is telling that something also changed during this period in the perception of the artist friends and the self-perception of the artists. The artistic signature becomes central.

DS: Yes. And strangely enough, the period of collaborations comes to an end with this album in 1942. After the Album Grasse, there are no further collaborations with Hans Arp.

SZ: Only cooperations.

DS: Yes, only cooperations.

Hans Arp, Sonia Delaunay, Alberto Magnelli, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Album Grasse, 12 loose sheets with 10 color lithographs, printed 1950. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich

Cooperations and Alliances

SZ: A late and spectacular example of such collaborations is the volume Poésie des mots inconnus by the publisher and book artist Ilya Zdanevitch Iliazd. In 1949, as a counterreaction to the Parisian Lettrists who claimed sound poetry as their own invention, Iliazd compiled predecessors of sound poetry going back to the Dada period, combining a poet and a visual artist on single pages. These were then each folded four times and loosely placed in the book, unbound, resulting in a unique dramaturgical composition—in fact, a performative book. When the pages are unfolded, it functions as its own school of seeing.

DS: This is a masterpiece. An absolute masterpiece! Michaela, I think you would agree as a publisher that everything is just right—from the choice of authors and illustrators to the feel. A very cheeky exercise! Iliazd pokes fun at the French tradition of having an artist’s binding made for every book. Iliazd knew exactly that the people who bought it would bring it straight to the bookbinder and say, "Make me a nice cover!" And that’s why he impudently writes on the first page: "Ne coupez pas mes pages!" Don’t cut my pages apart! A pre-emptive sideswipe—and it worked. I’ve never seen a copy that then ended up in a binding of a master binder.

SZ: And it’s a grandiose collection of representatives from the most diverse tendencies within the avant-garde. And among them again: Hans and Sophie. Despite all the differences among Arp’s individual collaborations and cooperations, one thing remains in common: they were produced against the backdrop of various constellations of artists in the star-filled sky of the avant-garde, from the Dadaists to the Surrealists to Concrete artists. In the process, Arp, acting as a kind of comet, traverses with his tail the most diverse, often even hostile constellations. He could go from a meeting of the group "Cercle et Carré," which had been founded in 1929 in deliberate opposition to the Surrealists, and walk over to a bar and join his friends André Breton or Paul Éluard. This is unique in the history of the avant-garde.

DS: More than unique! It’s utterly astonishing. And even more notably: he never had a falling out with anyone! Because even among the Dadaists there was trench warfare between the Zurich Spiegelgasse Dadaists and the Germans, then of course between the Paris Dadaists and Surrealists. Arp was never really a member of the Surrealists, but he was celebrated and accepted as a Surrealist. Sometimes I have the feeling that Arp was simply a charmer. Nothing could touch him. Things always went his way. Everyone could interpret something into his amorphous forms—sometimes Surrealism, sometimes Concrete art.

MU: But shouldn’t this be viewed as an achievement of the artist couple, Hans and Sophie?

DS: Absolutely! This can be seen in the unjustly forgotten magazine Plastique/Plastic, which Sophie edited from 1937 to 1939. It starts with an issue on Suprematism, then one in which she prints the "Dimensionisme" manifesto, before the final issues publish the collaborative novel L’homme qui a perdu son squelette, whose contributors include Marcel Duchamp, Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst, Éluard, Arp and others. And she kept all the different figures networked, maintaining the correspondence between France and the exiles in the USA.

Four of the twenty-six sheets from Poésie de mots inconnus (Poetry of Unknown Words)—from left, prints and poems by Tristan Tzara, Joan Miró, Raoul Hausmann, Kurt Schwitters, Hugo Ball, and Hans Arp—published by Ilja Zdanevitch Iliazd, 1949. Other contributors include Antonin Artaud, Marc Chagall, Alberto Giacometti, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and others. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich

Issues of Plastique/Plastic, edited by Sophie Taeuber-Arp, including "No. 1, Malewitsch in Memoriam," 1937, "No. 2, Dimensionism," 1937, and "No. 4 & 5, L’homme qui a perdu son squelette," 1939. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth

MU: ‘Plastique/Plastic’ in particular had this transatlantic aspect, connecting Paris and New York and giving constructive works a visible platform in America. What is so important about that to you?

DS: I think this open international mindset was really Sophie’s strength. That’s quite clear. Arp was very jovial, circulating in different groups, but then the back-breaking work—the correspondence, the raising of funds—that was clearly performed by Sophie Taeuber. The famed Aubette, a cultural centre on Strasbourg’s main square with a café-restaurant, tea salon and cinema-dance hall, would never have been built in the late 1920s without Sophie Taeuber. Neither Theo van Doesburg nor Arp could have done it. They had an attitude of, ‘Sure, we’ll do something at some point,’ but the cohesive force for this project clearly came from Sophie.

SZ: You can see how important this organizing and unifying spirit was in documents and photos from Meudon/Clamart. Everyone from Kurt Schwitters, Wassily Kandinsky, Francis and Gabrielle Picabia to Max Ernst, etc., is sitting in the garden and letting her attend to them. Of course she took part in these discussions as well, but someone had to hold it all together and that is often the task of a publisher, too—to sacrifice oneself in a certain way.

MU: Publishing is actually a service—and also an advance of money. And of course, Sophie Taeuber was the one who made a living. The more I learn about her, the different roles she took on, the more interesting she becomes. And she was also an active member of the Swiss artists’ group ‘Allianz.’ ‘Allianz’ is also an example of the phenomenon of a group of artists founding a publication entity—although the driving force behind the Allianz publishing house was mainly Max Bill, who wanted to give these artists a forum. You have many pieces from the Allianz publishing house. Are there any that are particularly important to you?

Clockwise from top left, contributions by Max Bill, Sonia Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp to ‘10 Origin,’ a portfolio of six linoleum cuts, three woodcuts, and one lithograph by Hans Arp, Bill, Delaunay, César Doméla-Nieuwenhuis, Kandinsky, Léo Leuppi, Richard Paul Lohse, Alberto Magnelli, Taeuber-Arp and Georges Vantongerloo, 1942. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / Angela Thomas Schmid / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

DS: 10 Origin is one of the most compelling books or portfolios for me. It’s a hodgepodge of artists. When you first leaf through it, you wonder, what’s the connection? But I think Bill did see a connection, an alliance of artists. The fact that someone like Leo Leuppi, who has been completely forgotten, is put on the same level as Kandinsky is astonishing at first. But if you let these sheets have their effect on you, you notice the things in them that connect. And Bill was so ingenious with his typographic skills that he designed a modern aesthetic in the late 1930s and ’40s which still holds up in the 21st century.

MU: And the copy you have here is a very special one. It is interesting in terms of contemporary history and to a particular extent biographically.

DS: Yes, this one is really close to my heart. It was dedicated by Max Bill to his first wife Binia. Arp and Sophie Taeuber came to Zurich on the last train that was still allowed to travel to Switzerland and signed their sheets with Bill. That must have been at the end of November or early December 1942, freshly printed as it were, shortly before Max Bill gave this copy to his wife for Christmas.

SZ: Plus the tragic aftermath.

DS: Yes, exactly, in January. Hans and Sophie were invited to dinner at Bill’s place in Höngg and stayed overnight. Actually, Sophie was supposed to sleep in the heated room and Arp in the unheated one. But Arp refused to go into the unheated one, and then tragedy took its course when Sophie attempted to warm up her cold room in the middle of the night and died of carbon monoxide poisoning. After her death, Max Bill published her last drawings, which she had made while living with her sister Erika Schlegel: Les derniers 9 dessins de Sophie Taeuber-Arp, also published by Allianz. They differ from what Sophie had done before. Suddenly these circles appear. There has also been speculation as to whether she even anticipated that there would be a closing of the circle. Arp then cast these nine drawings in metal reliefs. I can’t remember whether it has his name on it or hers. I hope it’s hers. But it must also be said that from the mid-1930s onwards, Arp only exhibited pictures of himself when works by Sophie were also on display. He said: we only come as a duo.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp in the office of the Aubette, Strasbourg, 1926–27 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth. Courtesy Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth and Hauser & Wirth

Drawing by Sophie Taeuber-Arp reproduced as a print in Hans Arp’s Poèmes sans prénoms, 1941. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Alex Delfanne

SZ: Another wonderful testament to this is the volume Poèmes sans prénoms with poems by Hans and illustrations by Sophie.

DS: Yes, this collaborative work was published as a private print in 1941 and contains three illustrations by Sophie. The paper is very plain and simple. It is really "un souffle," a breath, breathed. Although illustrations is perhaps the wrong word.

MU: What do you mean?

DS: Actually, it would be more appropriate to speak of illumination, don’t you think? Something came to my mind recently, speaking of illumination, of "enlightening": For example, Vingt-cinq poèmes has this gold foil on it, or Der Vogel Selbdritt. Arp loved these gold foils. Sophie too. And that’s when the "enlightenment" came to me, suddenly—Lord almighty! When Arp began with the Moderne Bund, what did he do? He made initials for the chapter headings, like the initials D, J and Z in Kandinsky’s almanac Der blaue Reiter. That’s just like how medieval monks illuminated the initial letters in books. It has qualities of an illumination, not an illustration. Illustration in the strict sense plays no role at all in Arp’s collaborations, because image and text are independent in all these publications. This is also proven by the fact that Arp partly reused the works in completely different books. In 1914, he made these line drawings, these equestrian fighting scenes, for the Bhagavad Gita. Two years later, for Huelsenbeck’s Schalaben schalabai schalamezomai, he reused four of these pen-and-ink drawings for Dadaist writings. So the drawings for the "Bible" of Hinduism suddenly find themselves in a Dadaist text! In 1958 he published the whole thing as a portfolio. He transferred these drawings onto copper plates. Here, we have the special edition with the negative prints. This raises the question: why did Arp publish something so atypical in 1958—not the Arp we know—again as a portfolio work? I think I have discovered the reason. In his copy, he has filled in these lines with ink. If you put the two sheets on top of each other, they are completely identical—you can take a look at them. And here you can see: with this treatment, this is the Arp we know from the Dada period.

11 Configurations, which includes 11 engravings by Hans Arp, an introduction by published Max Bill, and a text by Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, Allianz-Verlag, 1945. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich

A detail of one of the six original woodcuts by Hans Arp in Der Vogel selbdritt (The Bird Thrice with Itself), printed by Otto von Holten, 1920. © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich

The Great "Derdiedas"

SZ: Finally, I think there’s one other important thing. In one of the first Dada poems, Arp proclaims, "I am the great Derdiedas." I find that interesting in the context of his work. On the one hand, he is "der," the masculine article, but the feminine article, "die," of course also somehow embodies Sophie, and the neutral "das" stands for all the amorphous natural forms in his art, this neuter state of nature that he inscribes in his work. Thus he takes up these three pronouns as his life’s work. What’s particularly fascinating in this context is the blending of Hans and Sophie, beyond attribution to one or the other, with individual gender no longer playing a role, as the individual dissolves between the sexes, between man and nature, especially in artistic collaboration. That makes for a very beautiful thought in connection with Dadaism, which often had nihilistic features. In other words, it celebrated the obliteration of the person. But in Arp’s work, it is more of a dissolution, this cloud-like entity where everything is encompassed in a grand metamorphosis. An anonymous and enclouded "Derdiedas."

DS: But I think that what you’re saying now about the "Derdiedas" no longer applies after 1945. The "they" worked when Sophie was still there. Afterwards it was somehow different. The time of collaborations was over, and the collaborations were only peripheral. The constellations of Dada and Surrealism had also outlived their usefulness. Of course, there are still great works of book art like Soleil Recerclé from 1966, a kind of legacy. But overall, it seems that all these previous forms of collaboration in the context of artists’ books were no longer the same after Sophie’s death. Nothing against Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, not at all. But it was clearly a different artistic intensity with Sophie Taeuber. I also believe that Sophie and Arp were on an equal footing. Sometimes Sophie was perhaps even superior to Arp. But we shouldn’t play them off against one other, because the most exquisite secret to their work as artists remains the "duo," their innermost collaboration.

—

"Sophie Taeuber-Arp & Hans Arp: Cooperations—Collaborations" was on view at Hauser & Wirth Publishers HQ, Zurich, 9 April – 26 June 2021.

Daniel Segmüller is an antiquarian bookseller and book collector. In 1987 he and his wife Ruth Seiler founded the antiquarian bookshop Die Wolkenpumpe in Lucerne, which they ran part-time for more than 30 years. Their collection, which began 40 years ago, includes not only the Arp and Taeuber-Arp collection with almost 400 printed pieces, but also a book collection with works of Concrete and visual poetry as well as sound poetry. This reflects the collector couple’s love of experimental literature and 20th century art forms.

Stefan Zweifel is a curator, philosopher and author living in Zurich. He has translated Marquis de Sade, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Marcel Proust, among others. In 2020 he curated "Frauen Kunst Punk" at Strauhof Zurich with Bice Curiger, "Dance me to the end of love - ein Totentanz" at Kunstmuseum Chur with Stephan Kunz, and "Der erschöpfte Mann (The exhausted man)" at the Swiss National Museum with Juri Steiner.

Michaela Unterdörfer is the director of Hauser & Wirth Publishers. She is an art historian and philologist, and from 1997 to 2000, she was the curator at Kunsthalle Nürnberg and director of the Hauser & Wirth Collection from 2000 to 2005. Unterdörfer has authored and edited numerous publications on contemporary art. Unless otherwise noted, all artwork images courtesy Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth and Hauser & Wirth. Daniel Segmüller & Ruth Seiler Collection. Photo: Jon Etter