Winfred Rembert

Hard Times

30 May – 25 August 2024

Downtown Los Angeles

‘... when things aren't going right, you might have a few problems but think about me and the life I have to put up with and I'm still living. Hard times only learn you the lesson and give you the determination to be a success in life. When you are in a bad mood just stop and think about us and the love we have and that someday it will all be over and we can make up for all the hard times’

–Winfred Rembert, 1974

Explore the exhibition

Working in his signature medium of carved and painted leather, late American artist Winfred Rembert (1945 – 2021) dedicated the last thirty years of his life to creating a striking visual memoir. The consistently powerful and original oeuvre he left behind is a testament to the improvisational skill, determination and resilience required of a visionary shaped by a lifetime of extreme adversity. On 30 May, when Hauser & Wirth debuts the first-ever Los Angeles exhibition devoted to Rembert at its Downtown Arts District complex, West Coast audiences will finally have the opportunity to experience his story, told with beauty on leather.

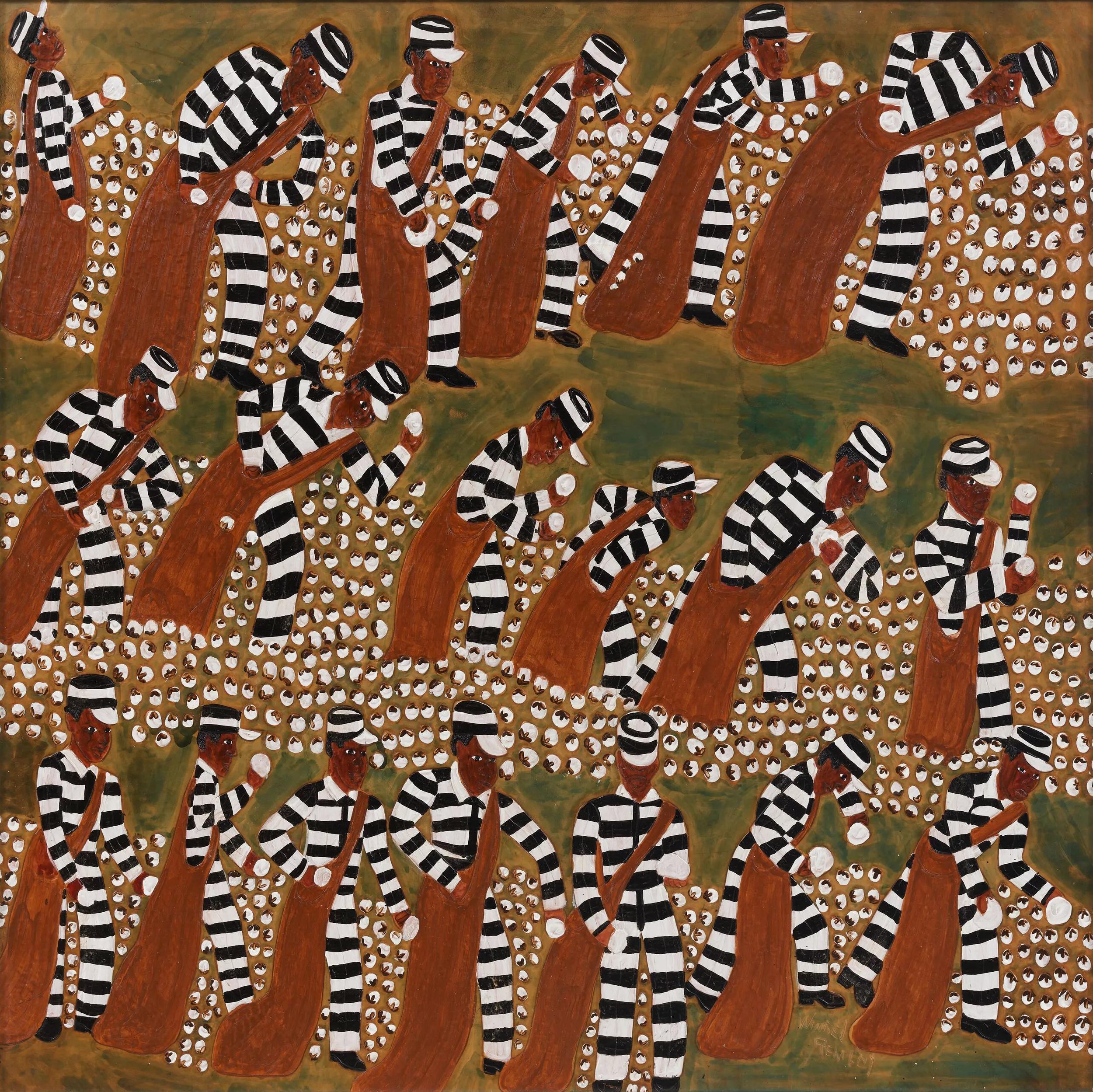

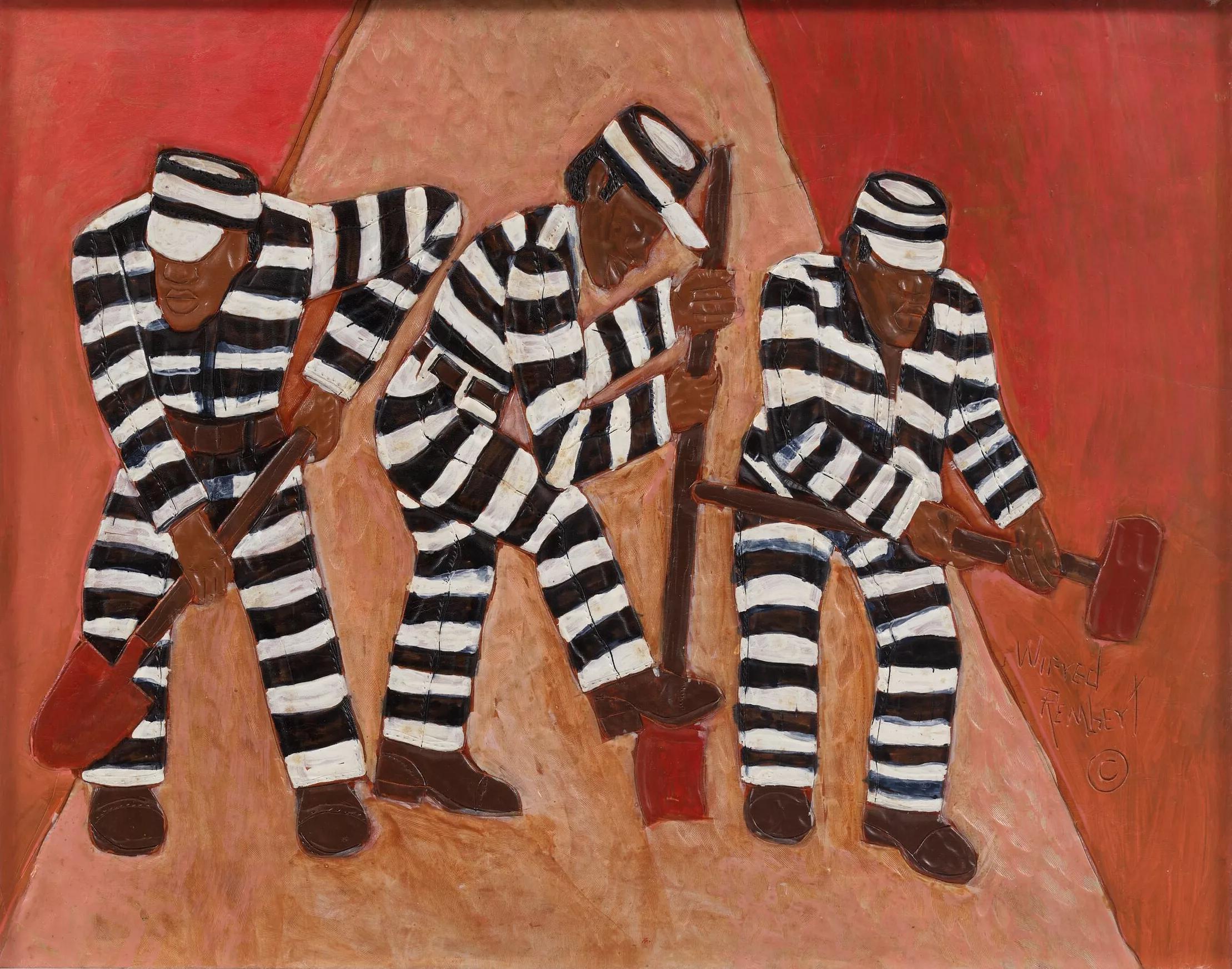

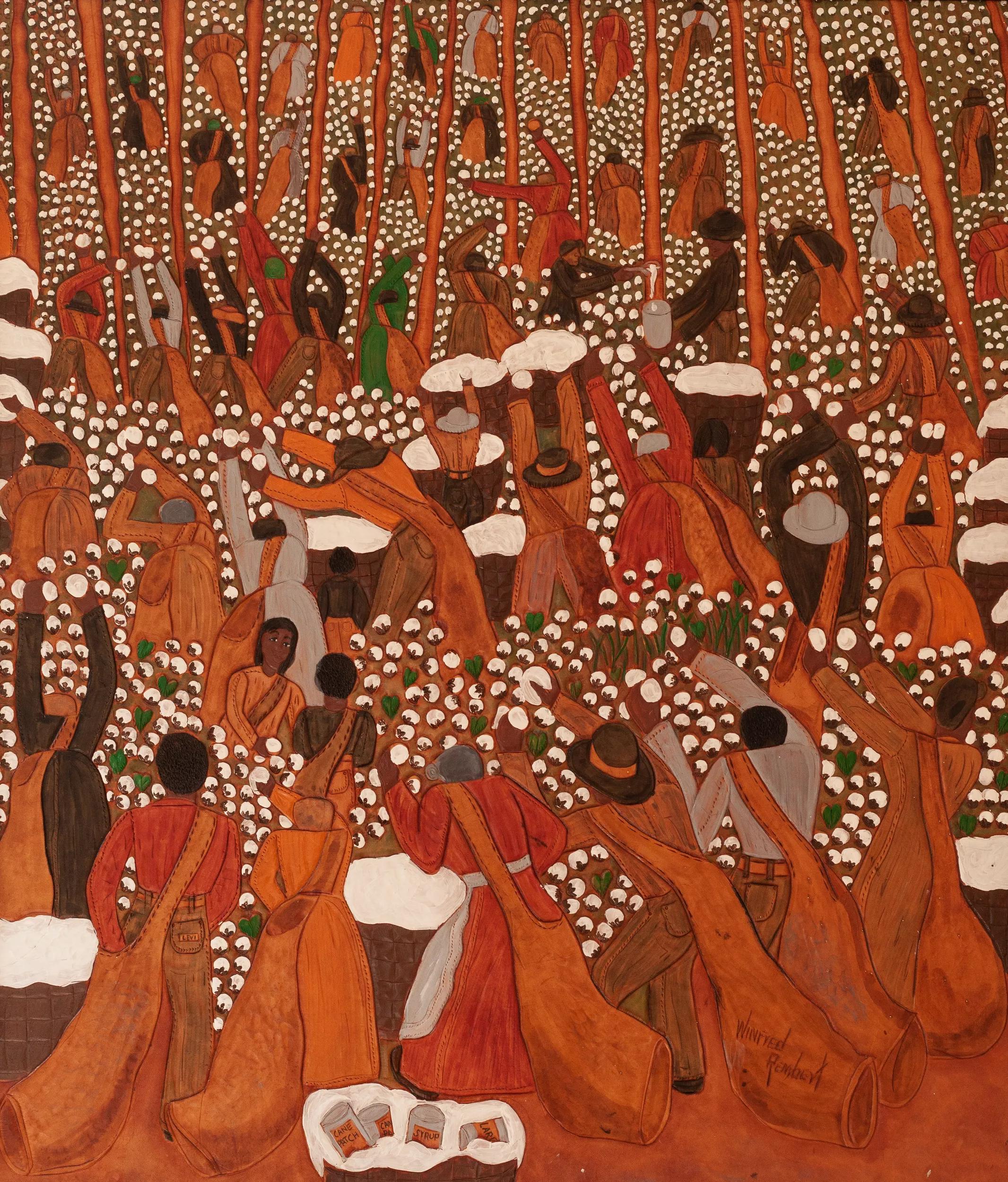

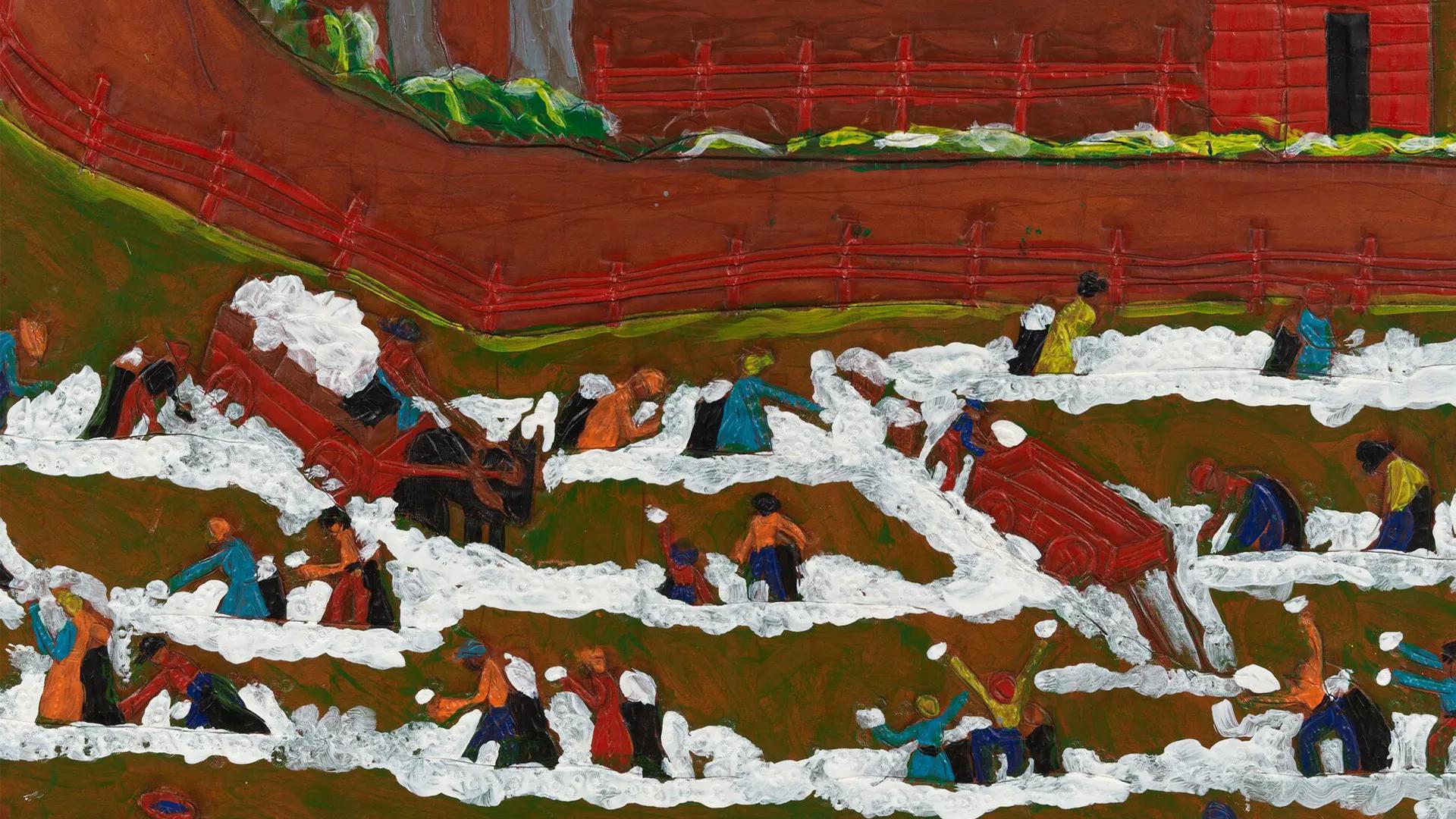

‘Winfred Rembert. Hard Times’ includes paintings from two of the artist’s most recognizable bodies of work—the Cotton Field and Chain Gang collections. Reflecting his upbringing on a sharecropping field in Georgia in the 1950s and his labor on a prison chain gang in the 1960s and ‘70s, the exhibition is dedicated to a pair of harrowing but formative chapters in Rembert’s life. At once figural and abstract, painted and sculptural, Rembert’s compositions feature varying palettes, ranging from the natural tones of the leather and the graphic use of black and white to the incorporation of vibrant blocks of color.

In his Pulitzer Prize winning memoir, ‘Chasing Me to My Grave,’ Rembert describes the cotton fields as his very first memory. He underscores the gravity of this nascent but indelible image, noting, ‘Looking up at his parents is the first thing a child is supposed to remember. Not me. It seemed like I opened my eyes to cotton.’ On view in the exhibition, ‘Hard Times’ (2003) is one of many paintings that depict workers bent over endless rows of white tufts that dot the landscape and subsume the visual plane. The sculpturally carved and painted leather here bear exquisite detail—each worker’s clothing is adorned with carefully crafted seams, featuring intricate beveling that adds unexpected depth. Equally novel is Rembert’s perspectival daring; the horizontal foreground sharply transitions to a rising verticality, absent of a discernible skyline.

Rembert’s works range from straightforwardly illustrative to extremely complex compositions that verge on abstraction. In the latter category is ‘All of Me’ (Date unknown), a work that teems with the bent bodies of men in black-and-white striped prison uniforms digging ditches and breaking rocks on the chain gang. Recalling the grueling physical labor he endured, Rembert states, ‘The mental cruelty may have been worse than the physical cruelty.’ Collectively the figures in ‘All of Me’ represent the multiple personae he adopted to survive such inhumane treatment while incarcerated. Refusing to be what the guards wanted him to be, he chose to evade their psychological traps by assuming all identities.

‘You have to play a role that isn’t really you. It’s like slavery. You have to meet all those demands and keep a sense of yourself as well. You don’t want to be identified with any of the roles you have to play, so you are all of them. It’s like all of you and everybody else around you are all tied up into one.’ Reflecting on this survival strategy, he stated, ‘I think if I hadn’t decided to play the All Me role on the chain gang, I wouldn’t have made it. Taking that stance—All Me—saved me.’

–Winfred Rembert

Patsy Rembert on Winfred Rembert

It was Rembert’s wife Patsy who encouraged the artist to begin tooling and painting the story of his life on leather—a skill he first learned from a fellow incarcerated man in Georgia—to transform his pain into redemption. Accompanying the exhibition at Hauser & Wirth is a presentation of their love letters written while Rembert was imprisoned from 1965 to 1974. These documents of their extraordinary exchange, shared here with the public for the first time, chronicle the journey of mutual affection and hope they took together during this traumatic period. In his memoir, Rembert marvels at the impact his writing had on Patsy, noting, ‘I convinced her to wait for me, just through letters,’ and adding, of their budding romance, ‘I just couldn’t believe good things finally happened to me.’

ON VIEW IN DOWNTOWN LOS ANGELES

‘Winfred Rembert. Hard Times’ is on view now through 25 August 2024 at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles. Please visit our location page to plan your visit.

Related Content

About the Artist

Winfred Rembert

Winfred Rembert (1945 – 2021) was born in Americus, Georgia and grew up in nearby Cuthbert, a rural railroad town located in the southwest region of the state, once at the center of the Deep South’s plantation economy. Living in Cuthbert during the era of Jim Crow, Rembert was exposed at a young age to the exploitative practices of the sharecropping system. Spending much of his childhood alongside family members working in the fields, Rembert received a limited education. Despite the infrequency of his attendance, a dedicated teacher by the name of Miss Prather recognized Rembert’s artistic talent and encouraged him to express his creativity through drawing.

As a teenager, Rembert was deeply influenced by the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement in Americus, where his active participation led to confrontations with law enforcement. In 1965, while attending a peaceful protest which was attacked by white antagonists, he fled from the assailants in a stolen car and was subsequently arrested for the theft. In 1967, still incarcerated while awaiting charges, Rembert escaped from jail. Following his ensuing capture by an angry white mob, Rembert survived a near-lynching. For the next seven years of his life, he was transferred to multiple penitentiaries within the Georgia prison system, enduring taxing physical labor while working on various chain gangs—a harrowing experience that would later prove central to the narrative of his extraordinary art.

Rembert learned how to tool and craft leather from a fellow prisoner—the technique he would later use to share his story with the world. Following his release from prison in 1974, Rembert married Patsy Gammage; the couple eventually settled in New Haven, Connecticut, and raised a family there. At the age of fifty-one, with his wife’s encouragement, Rembert began a full-time artistic practice. Combining his mastery of leather working with his skilled draftsmanship, he built a unique body of autobiographical paintings and continued to make art for nearly twenty-five years, before his death on March 31, 2021, at the age of 75.

Over the course of his career, Rembert embraced a variety of styles and pictorial strategies. His works range from purely illustrative to extremely complex compositions that verge on abstraction. In many of the early paintings, the materiality of Rembert’s media is immediately apparent. In such works, he rendered his figures in muted tones to compliment the natural color of the leather backgrounds. In other works, bright-colored pigments cover the entire surface of densely packed compositions. Over time, Rembert’s compositions accrued as a chronicle of his life, through pictorial landscapes of cotton fields and rhythmic compositions of field workers, freedom marches, church services, juke joints, and chain gangs in the Jim Crow south. In its narrative and formal qualities, Rembert’s work, with its corporeal texture, intense color, powerful patterns, and depictions of both hardship and pleasure, takes its place among the oeuvres of the most influential American figurative masters.

The York Square Cinema in New Haven launched a solo exhibition of Rembert’s leather paintings in 1998. Exhibitions followed at the Yale University Art Gallery and in New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles, among other locales and, in 2012, the artist received his first major solo museum presentation: ‘Amazing Grace’ debuted at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, New York, before travelling to four additional venues. This survey included more than fifty works and incorporated historical photographs of Georgia, as well as gospel music recorded and performed in the Museum’s galleries by Rembert. ‘Amazing Grace’ also showcased the feature-length documentary ‘All Me: The Life and Times of Winfred Rembert’ (2011), produced and directed by Vivian Ducat. When reminiscing on the title of the exhibition, the artist stated, ‘Amazing Grace is one of the songs I remember that was sung in the fields. I just loved to listen to the singing. Singing was the only thing about the fields that I loved.’

Winfred Rembert’s work is represented in the permanent collections of Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX; Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR; Flint Institute of the Arts, Flint, MI; Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, CT; Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, Athens, GA; Glenstone, Potomac, MD; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH; Legacy Museum, Equal Justice Initiative, Montgomery, AL; Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY; Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles, CA; Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI; Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN; Muskegon Museum of Art, Youngstown, OH; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Richard M. Ross Museum of Art, Wesleyan University, Delaware, OH; Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY; Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT; and Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Rembert’s work was highlighted in major exhibitions at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, AL in 2013; the Flint Institute of the Arts, Flint, MI in 2013; the Citadelle Art Foundation, Canadian, Texas in 2012; the Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY in 2012; the Greenville County Museum of Art, Greenville, SC in 2012; and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT in 2000.

The artist’s memoir ‘Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South’ (with Erin I. Kelly, Bloomsbury, 2021) was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 2022.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 11