Mike Kelley

Framed and Frame

23 September - 19 November 2016

London

Organised in collaboration with the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts.

For the gallery’s first UK exhibition devoted to Mike Kelley, Hauser & Wirth London presents a single monumental installation from 1999: ‘Framed and Frame (Miniature Reproduction ‘Chinatown Wishing Well’ built by Mike Kelley after ‘Miniature Reproduction ‘Seven Star Cavern’ Built by Prof. H.K. Lu’)’. Kelley was fascinated by Middle America’s many diverse and alternative subcultures, and through his work he became both a participant in and commentator on their cultural conventions and constructions. Taking Los Angeles’ marginalised Chinese-American community as its inspiration, ‘Framed and Frame’ explores the conceptual space between real and imagined places. Two photographic diptychs – ‘Color and Form’ (1999) and ‘Pre and Post (diptych)’ (1999 – 2000) – which Kelley viewed as important accompaniments to the installation, are also on display.

‘Framed and Frame’ recreates a local landmark in the Chinatown of downtown LA and consists of two separate sculptures divided by a wall. ‘Framed’ is a ‘wishing well’ in the form of a biomorphic, concrete, grotto-like landscape, covered with spots of spray-painted colour and cheap religious statuary and tossed coins on its ledges and niches. A secret crawlspace complete with a mattress, candles and condoms is revealed at the rear of the well. The adjacent ‘Frame’ is a 9 x 15 foot enclosure comprised of a cyclone fence, faux brick walls and barbed wire, decorated to resemble a Chinese gate. The original wishing well, referred to as the ‘Seven Star Cavern’, has an unclear history. Variously attributed, the wishing well has been modified over the years by locals and visitors. The courtyard and its greenery fell into neglect sometime after the 1960s but it remains a popular tourist attraction.

For Kelley, the wishing well projects the narrative of the Chinese-American community in LA, a story of persecution and exclusion, but also of cultural resilience and exchange. The conflation of Christian and Buddhist votives and Chinese-American kitsch illustrates the unique cultural collision that has evolved in the district since the 19th century. Writing about ‘Framed and Frame’, Kelley makes reference to the official opening of ‘New Chinatown’ in 1938, for which Chinese dignitaries, American politicians and Chinese-American film stars attended the parade and dedication ceremonies. He said, ‘the Chinatown wishing well represents a time in recent past when cultural exoticism on the civic level could flourish unchallenged. It represents an era in Los Angeles when Anna May Wong – the Chinese American actress […] could plant a willow tree, donated in her honor by Paramount Studios, on the concrete lump and make it seem a proud moment.’ Laws relating to immigration, citizenship and property at this time were however still discriminatory toward the Chinese, who were socially and politically marginalised. The ‘Seven Star Cavern’ visualises this disjuncture – the well symbolises hope and a collaborative spirit, whilst the surrounding fence alludes to confinement and segregation.

The wishing well also holds personal significance for Kelley due to the site’s proximity to Madame Wong’s and the Hong Kong Café – two venues at the centre of the LA punk scene in the late 1970s. The music scene brought a brief revival to Chinatown before the mid-1980s when the area became run down and crime-ridden.

In ‘Framed and Frame’ Kelley’s replica of the original ‘Seven Star Cavern’ and surrounding Chinese gate are displayed side by side as two distinct elements. By removing the framing device of the gate, the artist raises questions related to the ‘frame’ as a mechanism for instilling objects with meaning. Kelley linked the gate to the ‘frame’ of a painting, which he said, ‘focuses the attention of the viewer on the discrete forms within the painting’. The wishing well, considered separately from its frame ‘would appear to the casual viewer,’ he suggested, ‘as little more than a heap of scrap cement’; stripped of its enclosure, the monument is exposed to numerous interpretive projections. As such, ‘Framed and Frame’ is very much an extension of Kelley’s interest in exploring the conventional devices and visual tropes used to give ‘amorphous’ forms meaning, such as in his early series The Garbage Drawings (1988) and the Lump Drawings (1991). ‘Pre and Post (diptych)’ also belongs to this line of experimentation.

The secret crawlspace at the rear of the sculpture acts as a visual metaphor for Kelley’s interest in what he called ‘murky unspecific space’. Kelley found that the spray-paint dots haphazardly applied to the ‘Seven Star Cavern’ camouflaged the concrete form beneath, producing a confusing optical effect; the busily decorated surface added an additional layer of complexity. Kelley described this visual confusion as ‘orgasmic’, he said: ‘such space has an erotic appeal for me; it is the confused ‘nothing’ space of presexual consciousness’. In the diptych ‘Color and Form’, Kelley explores this discordant relationship between colour and form by digitally manipulating a photograph of a coral landscape shot in the Belle Isle Aquarium in Detroit MI.

To coincide with the exhibition, Hauser & Wirth London’s Book & Printed Matter Laboratory will be devoted to Mike Kelley. The gallery’s ongoing ‘Book Lab’ programme aims to encourage a deeper understanding of, and in-depth access to, artists’ work and wider practices. The Kelley ‘Lab’ focuses on process materials relating to ‘Framed and Frame’ from the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts archive – preparatory drawings, postcards and photographs of the original ‘Seven Star Cavern’. These are presented alongside key reference books and a looped screening of ‘Memory’, the 2005 ART21 documentary including the artist.

‘Framed and Frame’ heavily informed Kelley’s acclaimed Memory Ware series. The works are named after, and emulate, the Canadian folk art tradition in which domestic items such as vases, lampshades and mirrors are embellished with small mementos and souvenirs like coins, shells and beads. The Memory Ware works continued Kelley’s investigation into the emotional value that people invest in inanimate objects and nostalgic kitsch. Hauser & Wirth New York, 69th Street is staging a concurrent exhibition devoted to this body of work, 3 November – 24 December 2016. This is accompanied by a book with reproductions and discussion of the entire Memory Ware series.

Installation views

Related Content

About the Artist

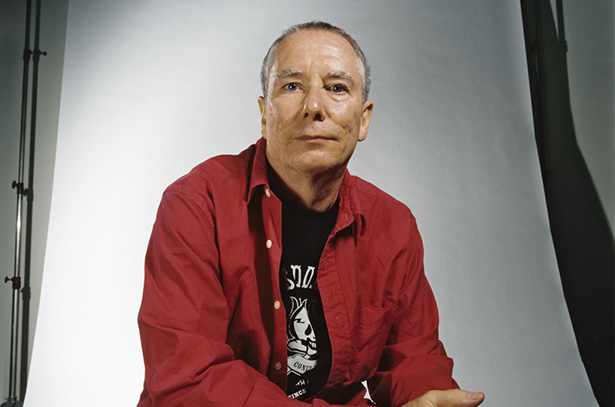

Mike Kelley

Mike Kelley is widely considered one of the most influential artists of our time. Originally from a suburb outside of Detroit, Kelley attended the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, before moving to Southern California in 1976 to study at California Institute of the Arts from which he received an MFA in 1978. The city of Los Angeles became his adopted home and the site of his prolific art practice. In much of his work, Kelley drew from a wide spectrum of high and low culture, and was known to scour flea markets for America’s cast-offs and leftovers. Mining the banal objects of everyday life, Kelley elevated these materials to question and dismantle Western conceptions of contemporary art and culture.

Starting out in the late 1970s, Kelley became known for performance and installation based works; he came to prominence in the 1980s with a series of sculptures composed of common craft materials and stuffed animals. His work later widened in scope and physical scale, exemplified by ‘Educational Complex’ (1995), the ‘Kandors’ series (1999 – 2011), ‘Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction’ series (2000 – 2011), and the posthumously completed public work ‘Mobile Homestead’ (2006 – 2013). These projects invoked a vast range of media and forms, illustrating the artist's versatility and underscored a number of Kelley's recurrent themes, such as repressed memory, sexuality, adolescence, class, and Americana, which were central to his artistic praxis. Throughout his career, Kelley also worked on curatorial projects, collaborated with many artists and musicians, and produced a formidable body of critical and creative writing.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12