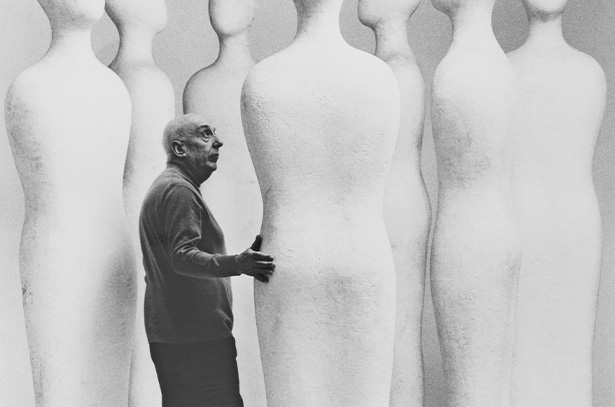

Beginning 20 April 2016, Hauser & Wirth is pleased to present ‘Fausto Melotti’, the gallery’s debut exhibition of works by the late Italian sculptor, installation artist, and poet, admired for his unique contribution to the development of mid-century European Modernism. In a compact survey spanning six decades and highlighting the remarkable breadth of Melotti’s career, the exhibition traces an artistic journey between the realms of abstraction and figuration. Coming of age in prewar Milan and living through the horrors of the Second World War, Melotti metabolized wartime devastation in his work by returning to Renaissance principles of harmony, order, geometry, and musical structure, which he integrated into a highly personal yet universally accessible artistic language that expresses the full range of emotional experiences in modern human existence.

On view through 18 June, ‘Fausto Melotti’ features drawings, ceramics, and sculptures from the early 1930s through the mid-1980s, including the artist’s plaster bas-reliefs, fantastical terracotta ‘Teatrini’ (Little Theaters), and signature lithe brass sculptures. The exhibition is curated by Douglas Fogle, former Chief Curator at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, and is accompanied by a new publication featuring historical material from the archive of Fondazione Fausto Melotti.

About the Exhibition

A pioneer of Italian art, Fausto Melotti (1901 – 1986) trained as a figurative artist studying under Italy’s leading Symbolist sculptor Adolfo Wildt at the Accademia di Brera in Milan. There he befriended fellow pupil Lucio Fontana in 1928, and in the following decade gradually shifted his focus to abstraction and a new non-objective art. Active in the artist milieu of prewar Milan, Melotti developed influential friendships with the Rationalist architects of Gruppo 7 and the abstract artists who gravitated around Galleria del Milione. With Fontana, he joined the ‘Abstraction-Creation’ movement, developing firm ideas about non-figurative art. In 1935, he wrote, ‘Greek architecture, Piero della Francesca’s paintings, Bach’s music, rationalist architecture – these are all ‘exact’ arts.’

The exhibition at Hauser & Wirth opens on the gallery’s first floor with an intimate presentation of abstract sculptures and bas-reliefs, exemplary of the artist’s first forays in abstraction. Reflecting the influence of his formative studies in music, mathematics, and engineering, these early works invoke the geometric purity in Melotti’s pursuit of ‘harmony’ and ‘counterpoint.’ Rendered in bronze, the rhythmic spiral of ‘Scultura n. 11’ (Sculpture No. 11) (1934) materializes harmonic melodies, while ‘Scultura n. 12’ (Sculpture No. 12) (1934 [1968]) invokes the artist’s investigations of reductive, planar architectural structures. These nuanced, rational forms of the 1930s reverberate in – and maintain a poetic continuity with – the works of Melotti’s postwar career.

Melotti’s ceramics of the 1940s respond to the pain, trauma, and despair that crowded his thoughts in the aftermath of the Second World War. Aerial bombings destroyed the artist’s studio in Milan and profoundly altered his artistic vision, precipitating a literal and symbolic rupture in his idealized pursuit of abstraction. His attention shifted to the craft and production of ceramics and terracotta. Rendered in chaotic polychromatic glazes, the enigmatic figures in these works illustrate the artist’s urgent and necessary return to figuration.

The Teatrini comprise an important terracotta series representing little metaphysical worlds that are enclosed within rectangular architectural structures and filled with fantastical objects and figures. Framing a single moment or multiple mise-en-scènes, Melotti’s theaters offer lively spontaneous narratives, from small poetic gestures to absurdist allegorical possibilities. One of the first pieces executed from this body of work, ‘Teatrino’ (Little Theater) (1930 – 1931 [ca. 1950]) is an early example of his geometric schematization of the figure. Anchoring his postwar practice throughout the 1940s and 1950s, other Teatrini, like ‘Le mani’ (The Hands) (1949), express mystical, poetic tableaux that bring to mind the Surrealist-inspired boxed assemblages of American artist Joseph Cornell.

By the 1960s, Melotti had faithfully returned to sculpture. He began using a new language built upon delicate threads and thin sheets of brass, iron, and gold to express a more resolved and distinctly humanist sensibility. ‘Monumento ai perseguitati politici’ (Monument to the Politically Persecuted (1962) joins a small number of explicitly political works. Poetically wrought from simple twists of brass, seven figures hang from chains attached to a gallows. Suspended in a fated moment of suffering beneath the glinting, jagged edges of a burnished sun, the sculpture is a memorial – an elegy on death, cruelty, and remembrance. At the same time, such other works as ‘La pioggia’ (The Rain) (1966 [1970]) celebrate the fleeting, beautiful moments of the everyday.

On the gallery’s second and third floors, the exhibition delves into Melotti’s late oeuvre with works spanning the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, and reveals his ongoing subtle redefinition of sculpture. A group of elegant, fragile spatial constructions is enriched by a dream-like and symbolic narrative quality. These weightless works seems to dematerialize in space. Crafted from shimmering rods of brass, ‘Tema e variazioni I’ (Theme and Variations I) (1968 [1984]) and ‘Contrappunto XIII’ (Counterpoint XIII) (1978 [1985]) evince an acoustic language. Encapsulating Melotti’s lyrical approach to sculpture, the curved and spiraling note-like forms here appear to move through the air, with their lines and shapes suggesting a complex orchestra of melodies and registers.

Melotti’s late work of the 1970s and 1980s is characterized by rhythmic geometric forms with an underlying humanist narrative that curator Douglas Fogle describes as 'quivering just on the threshold between the solidity of figuration and the immateriality of abstraction.' A constellation of images conjures unconscious revelations and a liminal realm between dreams, fables, myths, and memories. ‘Il viaggio della luna’ (The Journey of the Moon) (1973) is a playful, deceptively child-like work in which a line of figures must climb up a ladder to reach the moon. In such other works as ‘Tramonto kitsch’ (Kitsch Sunset) (1977) and ‘La sposa di Arlecchino’ (Harlequin’s Wife) (1979), Melotti invokes fragmented realities, inviting viewers to speculate on the mystery and theatricality of forms culled from his imagination.