Calder / Picabia

Transparence

14 June - 25 July 2015

Zürich

Installation views

About the Artists

Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder was born in 1898, the second child of artist parents—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter. In his mid-twenties, Calder moved to New York City, where he studied at the Art Students League and worked at the ‘National Police Gazette,’ illustrating sporting events and the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Shortly after his move to Paris in 1926, Calder created his ‘Cirque Calder’ (1926–31), a complex and unique body of art. It wasn’t long before his performances of the ‘Cirque’ captured the attention of the Parisian avant-garde.

In 1931, a significant turning point in Calder’s artistic career occurred when he created his first kinetic nonobjective sculpture and gave form to an entirely new type of art. Some of the earliest of these objects moved by motors and were dubbed ‘mobiles’ by Marcel Duchamp—in French, mobile refers to both ‘motion’ and ‘motive.’ Calder soon abandoned the mechanical aspects of these works and developed suspended mobiles that would undulate on their own with the air's currents. In response to Duchamp, Jean Arp named Calder's stationary objects ‘stabiles’ as a means of differentiating them.

Calder returned to live in the United States with his wife, Louisa, in 1933, purchasing a dilapidated farmhouse in the rural town of Roxbury, Connecticut. It was there that he made his first sculptures for the outdoors, installing large-scale standing mobiles among the rolling hills of his property. In 1943, James Johnson Sweeney and Duchamp organized a major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which catapulted Calder to the forefront of the New York art world and cemented his status as one of the premier American contemporary artists.

In 1953, Calder and Louisa moved back to France, ultimately settling in the small town of Saché in the Indre-et-Loire. Calder shifted his focus to large-scale commissioned works, which would dominate his practice in the last decades of his life. These included such works as ‘Spirale’ (1958) for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and ‘Flamingo’ (1973) for Chicago’s Federal Center Plaza. Calder died at the age of seventy-eight in 1976, a few weeks after his major retrospective, ‘Calder’s Universe,’ opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

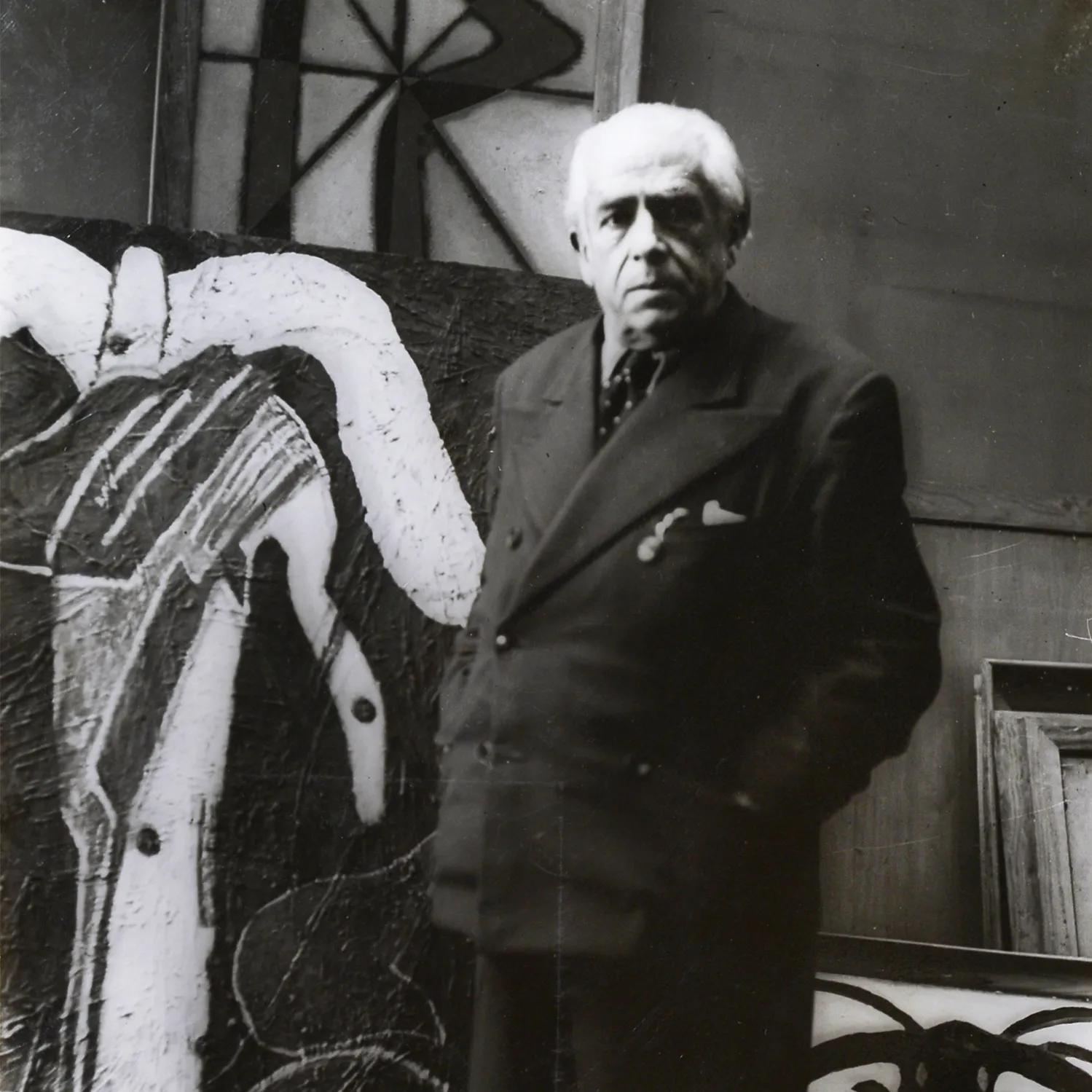

Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia was born François Martinez Picabia in Paris, to a Spanish father and a French mother. After initially painting in an Impressionist manner, elements of Fauvism and Neo-Impressionism as well as Cubism and other forms of abstraction began to appear in his painting in 1908, by 1912 he had evolved a personal amalgam of Cubism and Fauvism. In 1915—which marked the beginning of Picabia’s machinist or mechanomorphic period—he and Marcel Duchamp, among others, instigated and participated in Dada manifestations in New York. For the next few years, Picabia remained involved with the Dadists in Zurich and Paris, but finally denounced Dada in 1921 for no longer being ‘new.’ The following year, he returned to figurative art, but resumed painting in an abstract style by the end of World War II.

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10