Chromophilia

20 January – 9 March 2022

Zurich, Limmatstrasse

‘The obvious thing to say is that colour speaks for itself in art, and that any attempt to speak on its behalf is bound to fail. And yet for all the small talk that might happily be silenced forever, there is at the same time a bigger silence around the very subject of colour in art...’—David Batchelor, Chromophobia (2000)

Explore the exhibition

Colour is not a simple subject. In this group exhibition, titled ‘Chromophilia’ meaning the love of colour, the artists on view trace the complexity and possibility of colour, emancipated to differing degrees from line and form, within their chosen medium either synthetic or found – from liquid paint to sewn fabric, from coloured glass to LEDs, from neon to bindis.

‘Chromophilia’ brings together paintings, collages, sculptures and installations by artists including Phyllida Barlow, David Batchelor, Larry Bell, Louise Bourgeois, Frank Bowling, Geta Brătescu, Alexander Calder, Martin Creed, Günther Förg, Mary Heilmann, Jenny Holzer, Roni Horn, Bharti Kher, Yves Klein, John McCracken, Jason Rhoades, Pipilotti Rist, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Elisabeth Wild.

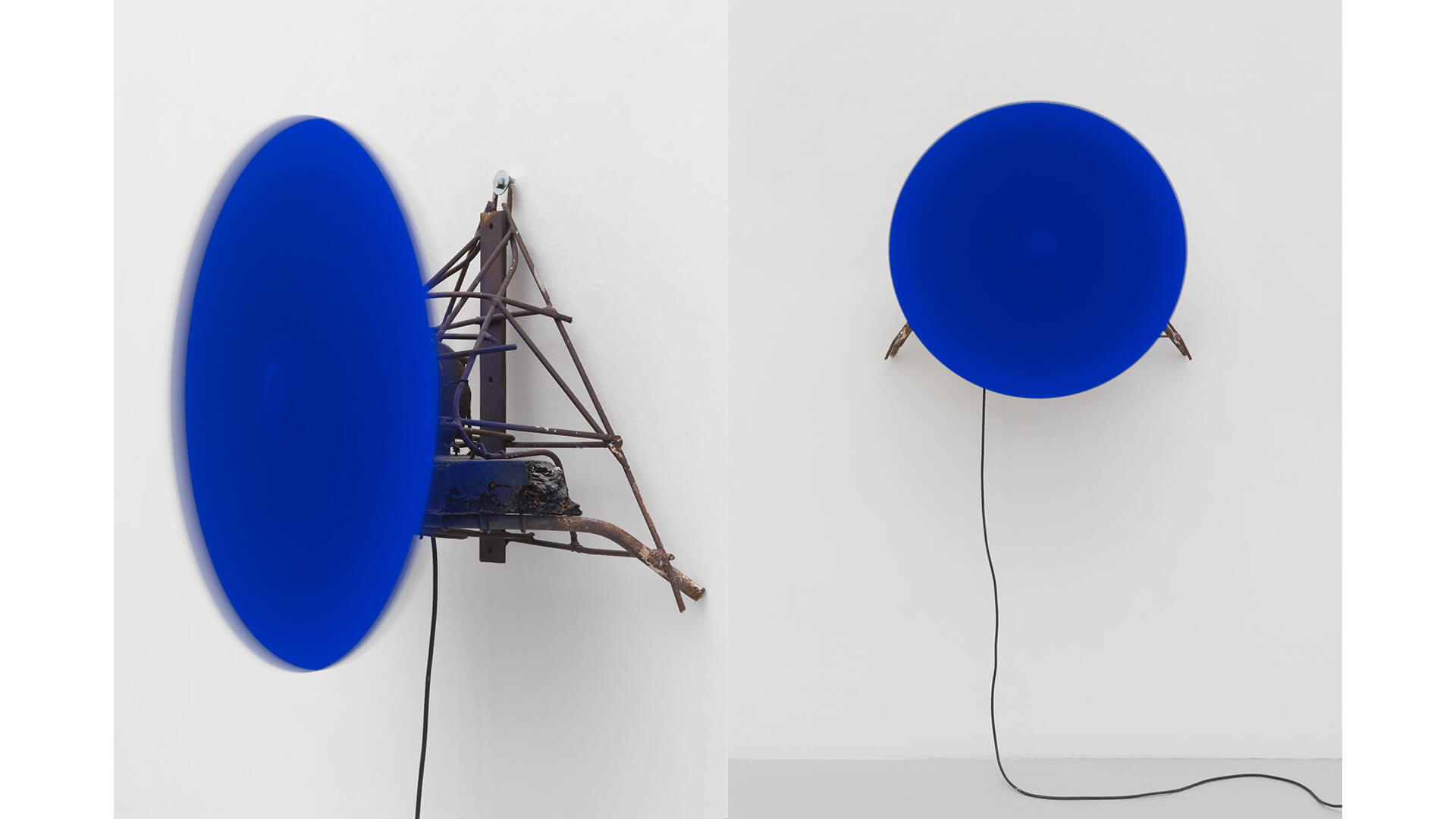

Until the 20th Century, colour in European, or Western, art was largely subordinated to line and form. The emancipation of colour in modern art came with the advent of movements such as impressionism, pointillism, fauvism, or the aptly named Blue Rider, and with the early development of modernist abstraction. The role of colour changed radically with the work of pioneering artists from Hilma af Klint to Hélio Oiticica, and with Yves Klein, whose work ‘Total Speed (Crazed Blue)’ 1958, a collaboration with Jean Tinguely, is on view in the exhibition.

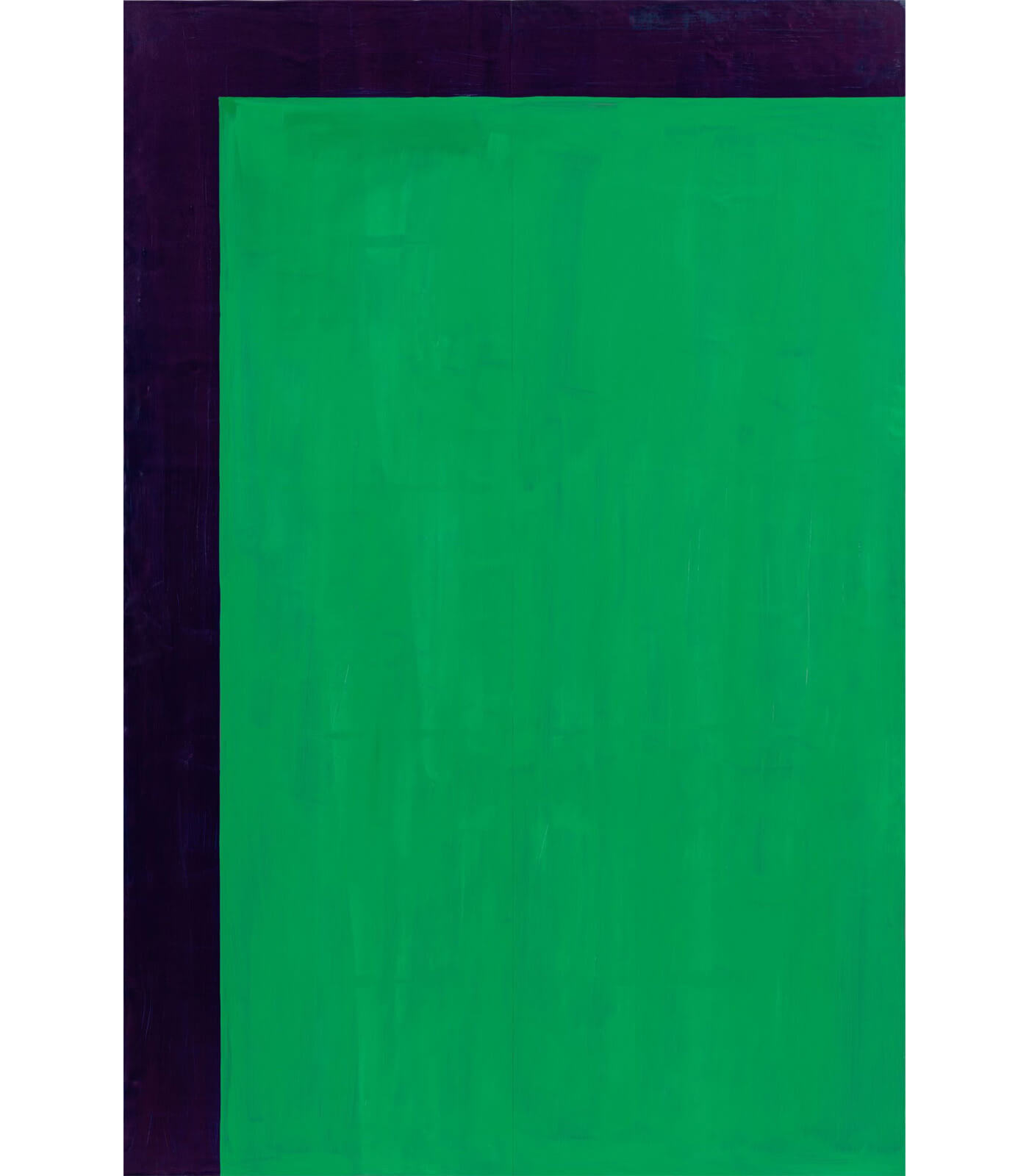

A concentration on colour remains a complex topic and the radical, though deceptive, simplicity of the use of single colours, particularly as monochromes, has been one of its most challenging aspects. Extending beyond the monochrome to explore close colour contrasts, Larry Bell’s early oil on canvas ‘Untitled’ (1959) ranges from orange and taupe to sienna and wine. This work anticipates his vibrantly tinted glass sculptures, such as ‘Pacific Red (IV)’ (2016-2017). Both show him to be a formidable colourist.

Colour has the capacity to work in myriad ways, representing opposing psychological states, from exuberant joy to crushing despair. Like music, brilliant colour can lift our spirits or stimulate memory; and artists have often turned to synaesthesia to develop their work.

Colour, however, can be and frequently is highly symbolic, and often it is politicised, representing partisan ideologies, playing a role in activism or denoting race and gender. Colour is not impartial and white is also a colour, not necessarily or merely its absence. Colour is historically defined and located; it changes according to its given cultural associations. In the short, dark days of winter we embrace intense and magnificent colour in festivals and celebrations that serve to reinforce identity.

Throughout his career Frank Bowling has engaged with the complexity of colour in painting, and has developed his own highly original approaches to chromatic abstraction. His work ‘Swimmers’ (2020) presents the viewer with a dense, layered surface, composed from acrylic paints and gels, collaged canvas and found materials or objects.

Bharti Kher’s sculpture ‘Peacock’ (2011) employs sari fabrics dipped in resin; by forming the bright green, shimmery blue and regal red fabrics into a peacock-like shape, Kher draws our attention to the transformation of everyday materials, likewise to the relation of colour to the body, and also to the important roles colour plays in India.

Occupying the full height of the exhibition space, Pipilotti Rist’s immersive installation ‘Wohnzimmerdisco ohne Angst (Living Room Disco without Fear)’ (2009) combines carpets and curtains, with sound and light to create a shower of vivid colour tones. David Batchelor’s ‘Chromodisc’ (2019) is a sculptural clock that uses light to move through the colour spectrum over the course of an hour. Overall, the artists included in ‘Chromophilia’ deploy colour always in inventive and extraordinary ways, helping us to see and experience our world anew.

On View in Zurich, Limmatstrasse

‘Chromophilia’ is on view now through 9 March 2022 at Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse.

About the Artists

Roni Horn

L’obra de Roni Horn es caracteritza per la incertesa i la impossibilitat de concloure-la. En tota la seva obra és important el seu interès per la naturalesa mutable de la identitat, el significat i la percepció, així com la noció de duplicitat, qüestions que continuen impulsant la pràctica de Horn.

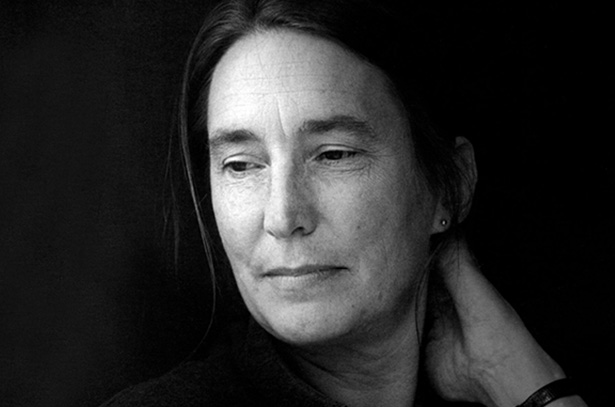

Mary Heilmann

Influenced by 1960s counterculture, the free speech movement, and the surf ethos of her native California, Mary Heilmann ranks amongst the most influential abstract painters of her generation. Considered one of the preeminent contemporary Abstract painters, Heilmann’s practice overlays the analytical geometries of Minimalism with the spontaneous ethos of the Beat Generation, and are always distinguishable by their often unorthodox—always joyful—approach to color and form.

Raised in San Francisco and Los Angeles, Heilmann completed a degree in literature, before she studied ceramics at Berkeley. Only after moving to New York in 1968 did she begin to paint. While most artists at that time were experimenting with the concept of dematerialization and demanding that painting should avoid any references to experience outside the material presence of the work itself, Heilmann opted for painting, rebelling against the accepted rules. ‘Rather than following the decrees of modern, non-representational formalism, I started to understand that the essential decisions taken during the creative process were more and more related to content. The Modern movement was over…’

Since then, Heilmann has created compositions that evoke a variety of associations. Her work may be non-representational and based on an elementary, geometrical vocabulary—circles, squares, grids and stripes—but there is always something slightly eccentric, casual about them. The simplicity of the forms is played down by a deceptive form of nonchalance: the contours are not clearly defined. In some paintings, amorphous forms appear to melt into each other like liquid wax. Splashes of color can be discerned, sharp edges bleed for no apparent reason, and the ductus of the brushstrokes is always perceptible. Heilmann’s casual painting technique conceals a frequently complex structure that only gradually reveals itself to the viewer.

Pipilotti Rist

Pipilotti Rist, a pioneer of spatial video art, was born 1962 in Grabs in the Swiss Rhine Valley on the Austrian Border and has been a central figure within the international art scene since the mid-1980s.

Astounding the art world with the energetic exorcistic statement of her now famous single channel videos, such as ‘I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much,’ 1986 and ‘Pickelporno,’ 1992, her artistic work has co-developed with technical advancements and in playful exploration of its new possibilities to propose footage resembling a collective brain. Through large video projections and digital manipulation, she has developed immersive installations that draw life from slow caressing showers of vivid color tones, like her works ‘Sip My Ocean,’ 1996 or ‘Worry Will Vanish,’ 2014.

For Rist, showing vulnerability is a sign of strength on which she draws for inspiration. With her curious and lavish recordings of nature (to which humans belong as an animal), and her investigative editing, Rist seeks to justify the privileged position we are born with, simply by being human. Her installations and exhibition concepts are expansive, finding within the mind, senses and body the possibility for endless discovery and poetical invention. ‘Pixel Forest,’ 2016, made from 3,000 thousand LEDs hung on strings, resembles a movie screen that has exploded into the room, allowing viewers an immersive walk through 3-dimensional video. As she herself puts it, ‘beside the energy-intensive exploration of the geographical world, pictures, films and sounds have been and are the spaces into which we can escape... The projector is the flamethrower, the space is the vortex and you are the pearl within.’

Since 1984, Rist has had countless solo and group exhibitions, and video screenings worldwide. Her recent solo exhibitions are 'Electric Idyll' at the Fire Station Doha (2024), 'Prickling Goosebumps & A Humming Horizon' at Hauser & Wirth New York and Luhring Augustine Chelsea (2023-24), 'Behind Your Eyelid' at Tai Kwun Hong Kong (2022), ‘Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor’ at The Geffen Contemporary, MOCA, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (2021 – 2022), ‘Your Eye Is My Island’ at MoMAK, The National Museum of Modern Art Kyoto and ART TOWER MITO (2021). ‘Åbn min Lysning. Open my Glade’ at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art Humlebæk Denmark (2019), ‘Sip My Ocean’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney (2017 – 2018), ‘Pixel Forest’ at New Museum New York (2016 – 2017) and ‘Your Saliva is My Diving Suit of the Ocean of Pain’ at Kunsthaus Zürich (2016), all resulted in record-breaking attendance numbers for each institution. A major exhibition is planned for summer 2025 at UCCA Beijing.

Bharti Kher

Born in London in 1969, Bharti Kher’s art gives form to quotidian life and its daily rituals in a way that reassesses and transforms their meaning to yield an air of magical realism. Now living between London, UK and New Delhi, India, her use of found objects is informed by her own position as an artist located between geographic and social milieus. Her way of working is exploratory: surveying, looking, collecting, and transforming, as she repositions the viewer’s relationship with the object and initiates a dialogue between metaphysical and material pursuits.

The bindi is an iconic personal affect of Indian women that is one of Kher’s signature materials and a loaded symbol. Since first appearing in her work in 1995, the bindi has inherited an aesthetic and cultural duality, a means to mix the superficial with the sublime. Kher explains: ‘Many people believe it’s a traditional symbol of marriage while others, in the West particularly, see it as a fashion accessory... But actually the bindi is meant to represent a third eye—one that forges a link between the real and the spiritual-conceptual worlds.’ Used as a material to articulate and animate her themes, bindis as such are not meant to be the central-motif of her work but rather act as a material, much like paint or clay, but with an inherent narrative. The bindis themselves undergo a shift in their initial cultural capital—they are defamiliarized, made to seem both scientific and mystical.

At the center of Kher’s practice are her sculptures, early examples of which featured fantastical hybrid characters, blurring the distinctions between humans and nature, ecology and politics. In line with this early practice, Kher continues to assemble, juxtapose and transform found objects that are witness to their own histories. Wooden wheels and architectural remnants, mannequin body casts and pillars all clash in mis-en-scenes of dystopia and grand orchestration. These elements are assembled in a hazardous manner; suspended from the ceiling, hanging from ropes, propped up and held from falling with the help of counterweights and balances; ultimately forming a heterogeneous narrative in which Kher further explores the artistic strategy of stripping objects of their meaning and making them open to misinterpretation and magic, creating alluring works of abstract beauty.

Phyllida Barlow

For almost 60 years, British artist Phyllida Barlow took inspiration from her surroundings to create imposing installations that can be at once menacing and playful. She created large-scale yet anti-monumental sculptures from inexpensive, low-grade materials such as cardboard, fabric, plywood, polystyrene, scrim, plaster and cement. These constructions were often painted in industrial or vibrant colors, the seams of their construction left at times visible, revealing the means of their making.

Barlow’s restless invented forms stretch the limits of mass, volume and height as they block, straddle and balance precariously. The audience is challenged into a new relationship with the sculptural object, the gallery environment and the world beyond.

‘There’s something about walking around sculpture that has the possibility of being reflective, like walking through a landscape,’ Barlow has said. ‘The largeness of sculpture has that infinite possibility to make one engage beyond just the object itself and into other realms of experience.’

Barlow exhibited extensively across institutions internationally and in 2017 represented Britain at the Venice Biennale.

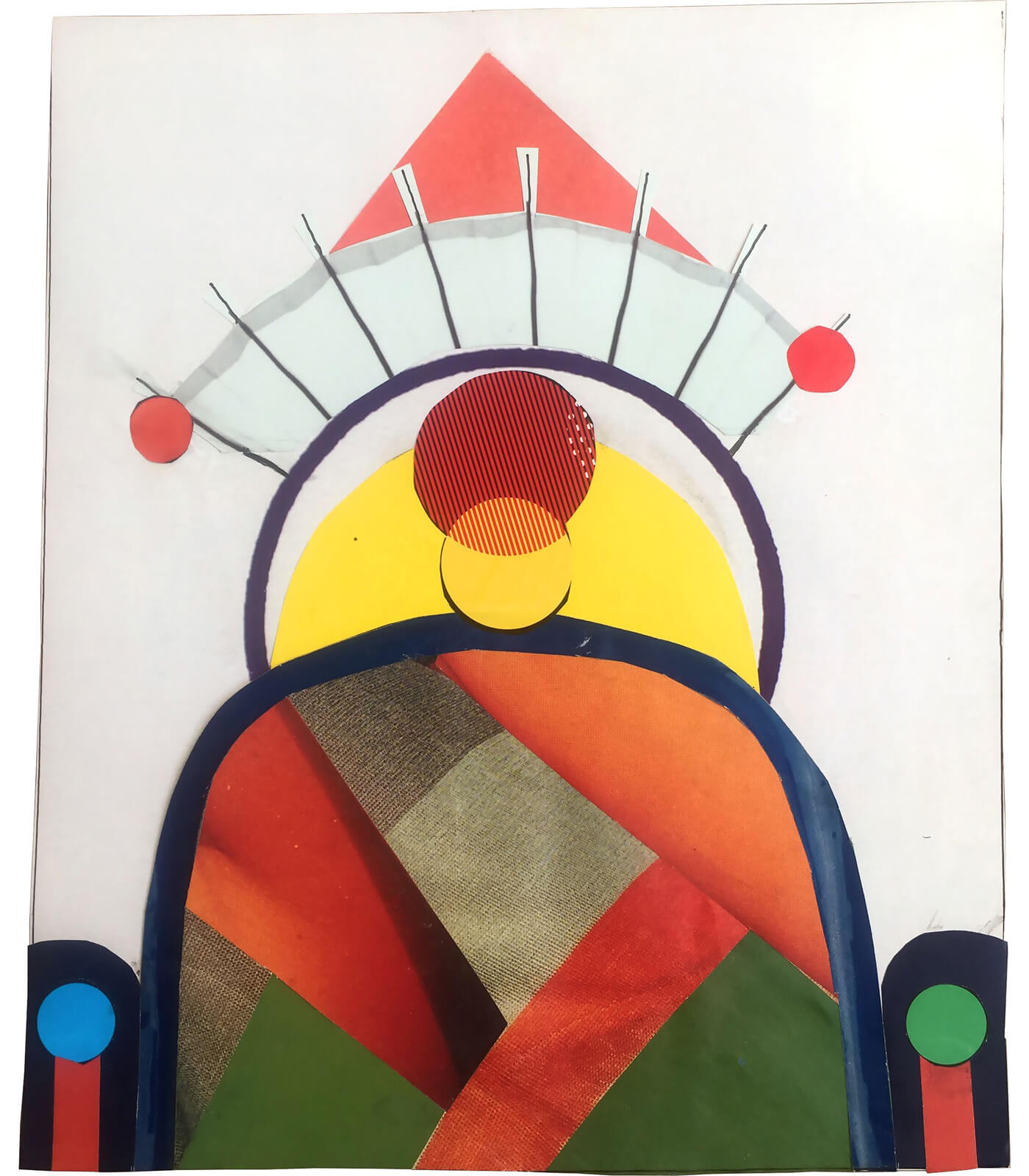

Geta Brătescu

One of the first representatives of conceptualist approaches in Romania, Geta Brătescu’s oeuvre comprises drawing, collage, textiles, photography, experimental film and performance. In her seven-decade career, she has published a number of books documenting her daily studio activities and personal experiences of art and travel.

Brătescu spent much of her working life in Bucharest under the Communist regime. She developed a deeply personal practice concerned with themes of identity, gender and dematerialisation. Her aesthetic—lo-fi, handmade, incorporating inexpensive, everyday materials—evolved from an attitude towards her studio as a safe environment of enclosure as well as a stage for playful invention. Memorialised in a key film, ‘The Studio,’ 1978 was a room of her own in which she could create work independently.

In addition to the objects and materials at hand, Brătescu was devoted to literature and would often draw inspiration from the stories of characters in famous texts. Aesop and Medea, Mother Courage and Faust, all played starring roles in her work, functioning as alter-egos and conduits for self-expression and frequently an oblique form of political subversion.

From 1945 to 1949, she studied at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Bucharest and at the Bucharest Academy of Fine Arts. In 1950 her studies were interrupted by the Communist government, and she was unable to complete her art education until 1971. Following her exclusion from university, Brătescu maintained a studio practice whilst working as an illustrator and graphic designer, becoming in the early 1960s the artistic director of the prestigious literary magazine, Secolul 20.

In 2008 Brătescu was honored with the title of Doctor Honoris Causa from the National Arts University in Bucharest for her contribution to the landscape of contemporary Romanian art. In 2017 she represented Romania at the Venice Biennale and was awarded by the President of Romania the Order of the Star of Romania.

Louise Bourgeois

Born in France in 1911, and working in America from 1938 until her death in 2010, Louise Bourgeois is recognized as one of the most important and influential artists of our time. For over seven decades, Bourgeois’s creative process was fueled by an introspective reality, often rooted in cathartic re-visitations of early childhood trauma and frank examinations of female sexuality. Articulated by recurrent motifs (including body parts, houses and spiders), personal symbolism and psychological release, the conceptual and stylistic complexity of Bourgeois’s oeuvre—employing a variety of genres, media and materials—plays upon the powers of association, memory, fantasy, and fear.

Bourgeois’s work is inextricably entwined with her life and experiences: fathoming the depths of emotion and psychology across two- and three-dimensional planes of expression. ‘Art,’ as she once remarked in an interview, ‘is the experience, the re-experience of a trauma.’ Arising from distinct and highly individualized processes of conceptualization, Bourgeois's multiplicity of forms and materials enact a perpetual play: at once embedding and conjuring emotions, only to dispel and disperse their psychological grasp. Employing motifs, dramatic colors, dense skeins of thread, and vast variety of media, Bourgeois's distinctive symbolic code enmeshes the complexities of the human experience and individual introspection.

Rather than pursuing formalist concerns for their own sake, Bourgeois endeavored to find the most appropriate means of expressing her ideas and emotions, combining a wide range of materials—variously, fabric, plaster, latex, marble and bronze—with an endless repertoire of found objects. Although her oeuvre traverses the realms of painting, drawing, printmaking, and performance, Bourgeois remains best known for her work in sculpture.

Bourgeois’s early works include her distinct 'Personages' from the late 1940s and early 1950s; a series of free-standing sculptures which reference the human figure and various urban structures, including skyscrapers. The ‘Personages’ served as physical surrogates for the friends and family Bourgeois had left behind in France, while also highlighting an interest in architecture dating back to her childhood. Her installation of these sculptures as clustered ‘environments’ in 1949 and 1950 foreshadowed the immersive encounters of installation art twenty years before the genre’s rise to prominence.

Bourgeois’s work was included in the seminal exhibition ‘Eccentric Abstraction,’ curated by Lucy Lippard for New York's Fischbach Gallery in 1966. Major breakthroughs on the international scene followed with The Museum of Modern Art in New York's 1982 retrospective of her work; Bourgeois's participation in Documenta IX in 1992; and her representation of the United States at the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993.

In 2001, Bourgeois was the first artist commissioned to fill the Tate Modern’s cavernous Turbine Hall. The Tate Modern’s 2007 retrospective of her works, which subsequently traveled to the Centre Pompidou in Paris; The Guggenheim Museum in New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; and The Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C., cemented her legacy as a foremost grande dame of late Modernism.

Header image: Louise Bourgeois, ARCHED FIGURE, 1993 © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

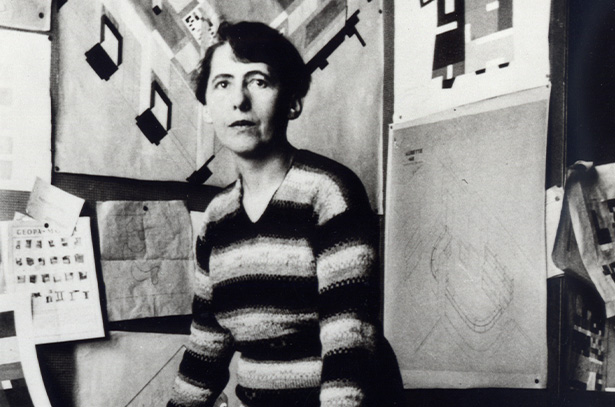

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889 – 1943) is one of the most important artists of the twentieth-century avant-garde and is considered a pioneer of Constructivist art. Reconciling extremes with confidence—Dada and Geometric Abstraction, fine art and utilitarian objects—Taeuber-Arp’s works boldly engaged with the intellectual context of international modernism. Through her multi-faceted approach to media, she challenged traditional hierarchies between fine and applied art, and asserted art’s urgent relevance to daily life. Taeuber-Arp defied categorization during her brief career through her work as a painter, sculptor, architect, performer, choreographer, teacher, writer, and designer of textiles, stage sets and interiors.

Born in Davos, Switzerland, Sophie Taeuber-Arp began her studies at the School of Applied Arts in St. Gallen between 1906 and 1910, studying textile design and embroidery. She later moved to the experimental workshops of Hermann Obrist and Wilhelm von Debschitz in Munich, where she learned a variety of techniques in fine and applied art and architecture, before spending a year studying weaving at the School of Arts and Crafts in Hamburg. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 forced Taeuber-Arp to return to Switzerland, where in 1915 she took lessons in Ausdruckstanz (expressive dance), with the choreographer Rudolf von Laban and the revolutionary dancer Mary Wigman. The same year, during a visit to the Galerie Tanner in Zurich, she met her future husband Hans Arp, whom she married in 1922.

Between 1916 and 1919, Taeuber-Arp was a key member in the Zurich Dada movement, performing in modern expressive dances at the Cabaret Voltaire and the Galerie Dada. From 1916–1929, Taeuber-Arp taught textile design at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts. Her teaching methods in color theory and abstraction were informed by her own practice that deliberately favored mediums and techniques that challenged accepted hierarchies—whether that was through her pioneering use of the grid, free-flowing geometric forms or abstracted figures. In these years, Taeuber-Arp produced collages, watercolors, textile works and stage sets, marionettes and tapestries, utilizing a unique interplay between color and form which would later solidify her place as an early founder of Constructivist art.

1926 was a turning point in Taeuber-Arp’s career, when she was commissioned to design the interior of the Aubette, a cultural center, in Strasbourg—a project she asked Hans Arp and Theo van Doesburg to collaborate with her on. Once completed in 1928, van Doesburg devoted an issue of his journal De Stijl to their groundbreaking design of a public environment that inextricably melded art with daily life.

The Aubette commission gave Taeuber-Arp and her husband economic freedom that allowed them to move to Meudon, near Paris, where she conceived and designed their house and studio and some of its furniture. This marked the beginning of the most productive period in Taeuber-Arp’s life. She joined various artistic collectives from Cercle et Carré to Abstraction-Création and the Swiss group Allianz alongside fellow artists such as Georges Vantongerloo, Piet Mondrian and Max Bill, and founded and edited the radical art magazine Plastique. Arp’s and Taeuber-Arp’s house in Meudon became a meeting place for artists, writers and other intellectuals. Their circle of friends included the artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Joan Miró, and Marcel Duchamp. Between 1929 and 1943, Taeuber-Arp exhibited in 40 exhibitions across the globe.

Taeuber-Arp and her husband fled to Southern France when the Nazis invaded Paris, before crossing over to Zurich in late 1942. The following year she died tragically and prematurely from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning.

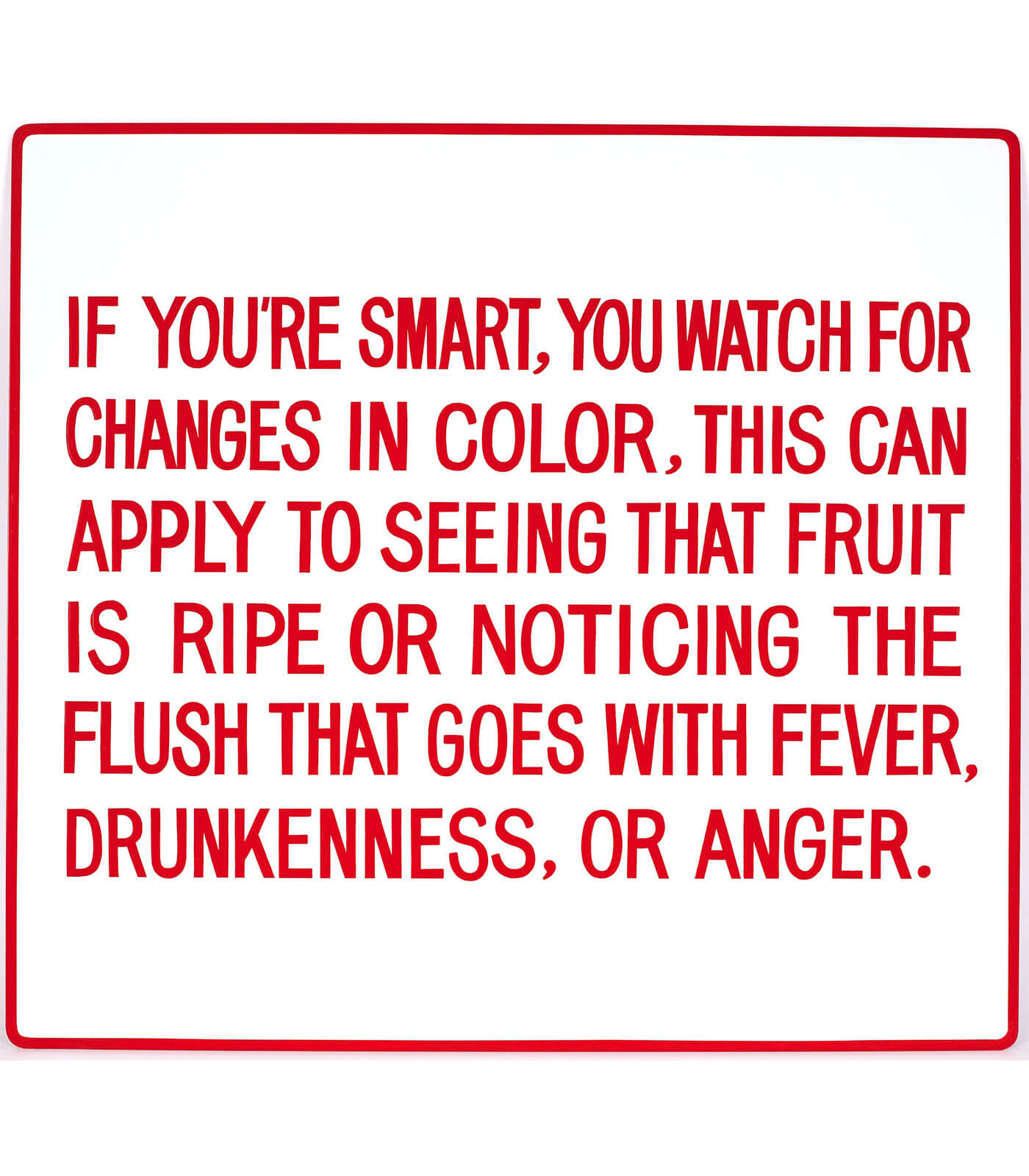

Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer is an American conceptual and installation artist whose work deploys text in public spaces across an array of media, including electronic signs, carved stone, paintings, billboards, and printed materials. Holzer’s oeuvre provokes public debate and illuminates social and political justice. Celebrated for her inimitable use of language and projects in the public sphere, Holzer creates a powerful tension between the realms of feeling and knowledge, with a practice that encompasses both individual and collective experiences of power and violence, vulnerability and tenderness.

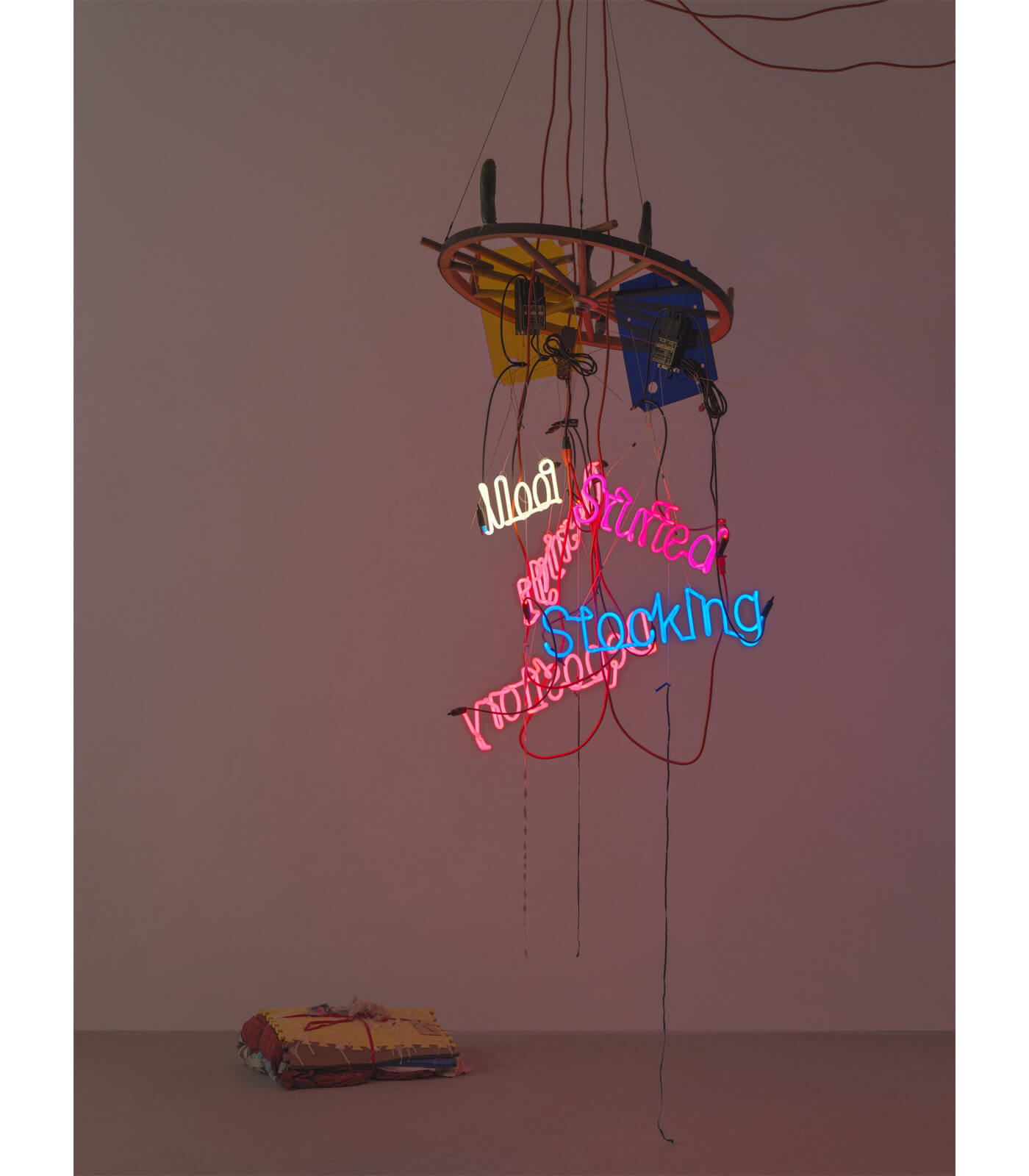

Jason Rhoades

Jason Rhoades (1965 – 2006) was a visionary artist and world builder for whom sculpture and myth were intertwined forms of construction. His epic assemblage installations established him as a force of the international art world in the 1990s, while based in Los Angeles. America was his art’s imaginative subject, which he represented with a provocative sense of irony and materialism, along with disarming humor and authentic identification.

Working on an architectural scale, Rhoades created immersive environmental sculptures that deployed copious quantities of consumer goods (Q-tips, computers, knickknacks), building supplies (plastic buckets, Sheetrock, extension cords), media (video games, hip-hop music, porn) and neon light. Imbued with a barely contained sense of chaos, these works are also highly crafted and surprisingly formal in their composition. Pattern, order, information networks, narrative threads, color and line give shape to Rhoades’ installations as diagrammatic depictions and systems of meaning. He considered art a tool for pursuing life’s big questions and dedicated major works to exploring the act of creation as signified by a garage, the brain, Brancusi’s studio and a penis, among other metaphorical sites. The car was also instrumental to Rhoades’ project as a readymade sculpture, as a conceptual space akin to the studio and as a vehicle for the driving ambition he held for his art. 'If you know my work', he said, 'you know that it is never finished'.

Martin Creed

‘Creed is a social artist; the true magic of his work lies in the way it interacts with people and places.’

—Jonathan Jones, ‘Martin Creed’s stairway to heaven,’ in The Guardian, London, UK, 1 August 2011, ill. (on Work No. 1059)

Frank Bowling

For over six decades, Frank Bowling has relentlessly pursued a practice which boldly expands the possibilities and properties of paint. Ambitious in scale and scope, his dynamic engagement with the materiality of his chosen medium, and its evolution in the broad sweep of art history, has resulted in paintings of unparalleled originality and power. Bowling has been hailed as one of the foremost British artists of his generation. Born in British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1934, he arrived in London in 1953, graduating from the Royal College of Art with the silver medal for painting in 1962. By the early 1960s, he was recognized as an assured force in London’s art scene. During this period, his highly individual language of painting, which emerged from expressionistic figuration and pop art, encompassed autobiographical elements and the artist’s socio-political concerns.

Bowling went on to divide his time between the art scenes in London and New York, maintaining studios in both cities. This transatlantic orientation was to see his early engagement with expressive figuration and pop art shift to an immersion in abstraction which continues in his practice today. Visible in his work are the legacies of both the English landscape tradition and American abstraction from which Bowling honed a distinctive vocabulary, combining figurative, abstract and symbolic elements. As Bowling has explained, ‘I was always very conscious of scratching out and of new interpretations replacing the old; updating traditions.’

A major reorientation in Bowling’s practice came in 1966 when he relocated from London to New York, at a time when the artistic scene was divided along lines of formalism and politics. In New York, Bowling pushed his work in new directions. He met Jasper Johns and engaged in a dialogue with his contemporaries, such as Jack Whitten, Mel Edwards, Al Loving, and Daniel Johnson. In 1969, Bowling organized, curated, and wrote the catalogue essay for ‘5+1’, a notable exhibition at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, and Princeton University showcasing the work of five African American abstract artists as well as his own recent paintings. He expressed frustration at the critical invisibility of Black artists and the narrow parameters by which his art and that of his peers was being assessed. Through his writings, as a contributing editor of Arts Magazine (1969-1972), he resisted what he saw as the reductive categorization of ‘Black Art’ as purely political in subject matter, staking a claim for abstraction.

By 1971, Bowling’s visionary approach to painting fused abstraction with personal memories. Concerns of color, surface and process gained in prominence resulting in his iconic series of ‘Map Paintings’, which include the stenciled landmasses of South America, Africa and Australia and were exhibited that same year at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Over the years, the points of reference in his work reflect Bowling’s interest in a wide scope of art history, from Constable and Turner, to Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. From 1973 to 1978, Bowling experimented with ideas of chance and ‘controlled accidents’, pouring paint from a two-meter height to create his visually arresting ‘Poured Paintings’, an expansion from color field painting.

Bowling returned to London in 1975 but continued to spend significant periods in New York. His sculptural paintings of the 1980s include embedded objects (newsprint, plastic and foam) and thickly textured canvases, and have been described as evoking landscape, riverbeds, and geological strata. In 1986, he exhibited a group of major new paintings at the Serpentine Gallery in London, curated by Ronald Alley, then Keeper of Modern Art at the Tate Gallery. Bowling shares Turner’s and Constable’s preoccupation with light, which is never more evident than in his expansive ‘Great Thames’ series of paintings of the late 1980s.

Today, Bowling’s mastery of the painted medium and explorations of light, color, and geometry incorporate the use of ammonia and multilayered washes. His restless reinvention of the painted plane endures in his current bodies of work which continue to break new ground through his use of thick impasto textures, acrylic gels, collage, stitched canvas, and metallic and pearlescent pigments. Bowling works every day in his South London studio, accompanied by his wife, Rachel, other family members and friends, forever driven by his fascination with exploring the vast and radiant possibilities of paint.

Bowling’s work has been exhibited extensively which has cemented his place in the post-war canon of contemporary and modern art. A turning point in Bowling’s career came in 2003 when his ‘Map Paintings’, which had been in storage and unseen since the early 1970s, were the centerpiece of the exhibition ‘Faultlines: Contemporary African Art and Shifting Landscapes’, at the 50th Venice Biennale. His work drew much attention and paved the way for him becoming a Royal Academician in 2005. Bowling was awarded the OBE for Services to Art in 2008 and a knighthood in the Queen’s birthday honors in 2020. His work is represented in over fifty collections worldwide and has been exhibited in numerous group and solo exhibitions, including the 2017–19 touring exhibition ‘Mappa Mundi’, the hugely successful retrospective at Tate Britain in 2019 and the major exhibition 'Frank Bowling: Americas’ which toured from MFA Boston to SFMOMA in 2022 - 23. Bowling is the subject of a BBC documentary, ‘Frank Bowling’s Abstract World,’ which coincided with the opening of the Tate retrospective. In 2022, he was awarded the Wolfgang Hahn Prize which honors exceptional contemporary artists.

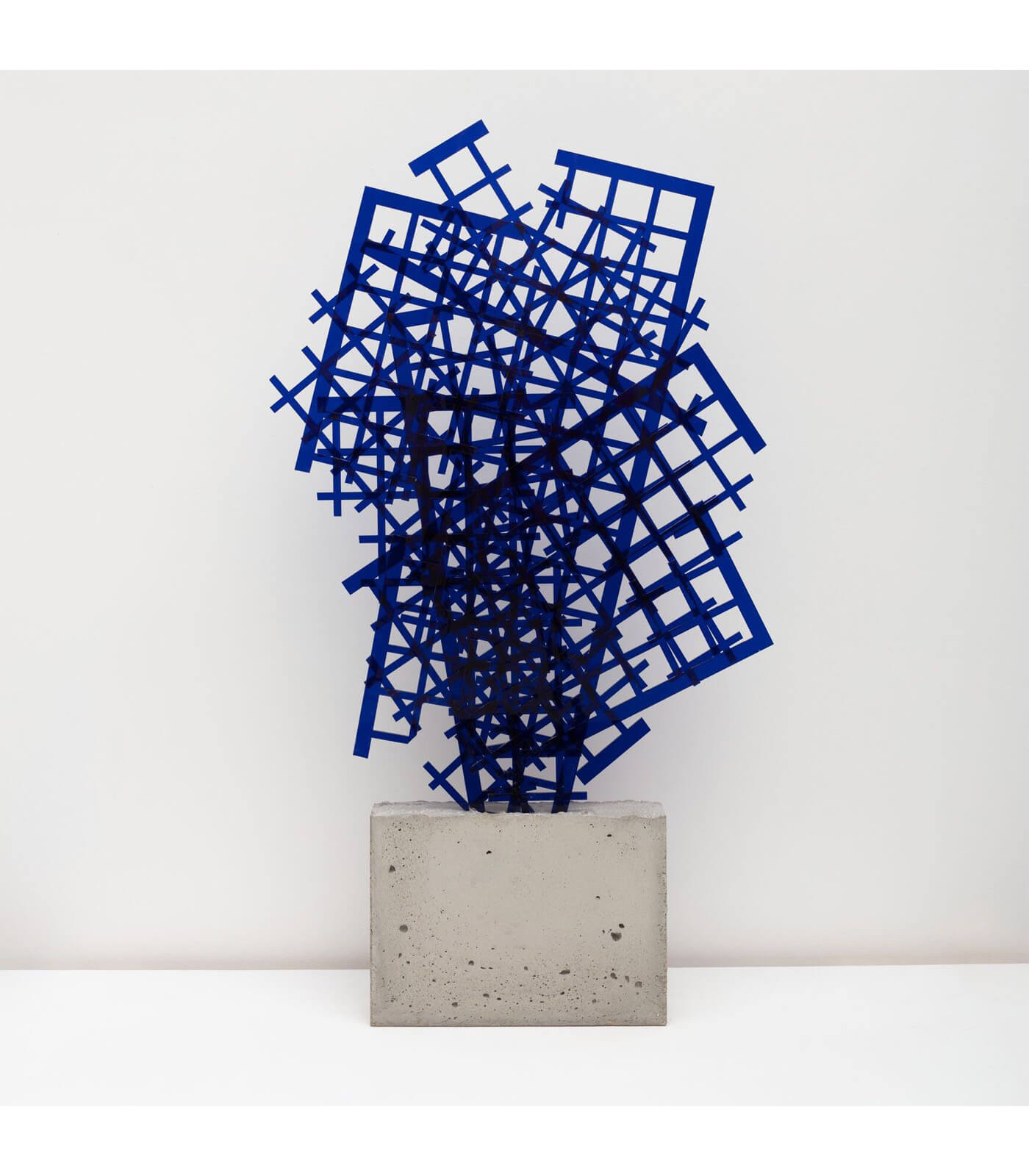

Günther Förg

Günther Förg was born in 1952 in the region of Allgäu, Germany. His career began in the early 1970s as a student at The Academy of Fine Art Munich. During his studies, Förg developed a practice grounded almost exclusively in grey and black monochrome. These early investigations into gray—also called ‘Gitter’ paintings—demonstrate the beginning of a lifelong commitment to conceptualism. As he stated, ‘Grey is nothing: not white, not black. Something in between. Not concerned with the figure. Something free.’ While the artist later incorporated color into his monochrome series, his use of gray represents a neutral foundation from which he conceived his oeuvre.

In the 1980s, Förg began utilizing photography, printing large-format images of culturally—and politically—significant architectural structures, from Bauhaus buildings in Tel Aviv to Fascist constructions in Italy. This diversification of material and form led Förg to abandon painting altogether, and for some years he pursued a purely photographic practice as a reaction against painting itself. He would later reflect that his use of photography was a method of ‘working closer to reality,’ stating, ‘what one paints is not reality.’

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, his photographic works achieved critical acclaim and were exhibited at major museums internationally, including the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland and The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York NY. During this time, Förg also began experimenting upon the exhibition space itself, painting over the gallery walls, and positioning photographs against his own paintings.

Förg entered a new phase of experimentation in the late 1980s, which brought him back to painting, but also included the embrace of new materials for him, such wood, copper, bronze, and lead. Förg’s renowned lead series—acrylic painted on sheets of lead and supported by wooden frames—blurs the line between painting and sculpture in an evolution towards object-making. Also initiated during the 1980s, his bronze sculptural practice indicates a painterly quality, with indentations and marks that are reminiscent of a brushstroke, as he attempted to replicate a moment frozen in time.

In pursuit of further artistic experimentation Förg began producing fragmented body-part sculptures in the early 1990s, describing this arrival at figuration as inevitable. These new works embraced the materiality of their making; the heavy, weathered, and scratched surfaces of the sheets of metal, lead, and wood hint at something that is simultaneously formal and expressionist, geometric and free.

By the beginning of the 21st century, Förg’s paintings had left the formality of Minimalism behind. In a new direction, he incorporated a brighter palette and more expressive hand with a series of grid-like marks and intersecting colors. These paintings—called ‘Gitterbilder’ (grid paintings)—command a similar freedom of form and sensuality that has led to critical comparisons to Cy Twombly. Other works from this era portray vast canvases of negative space interrupted by colorful, gestural hatching and mark-making. Förg’s ultimate return to expressive painting indicates a completion of sorts—a full-circle arrival at painting as a synthesis of experimentation, rooted in art history. In the artist’s own words, ‘I think painting is a resilient practice; if you look through the history of painting it doesn’t change so much and we always see it in the present. It is still now.’

Image credit: © Wilhelm Schürmann, Herzogenrath

Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder was born in 1898, the second child of artist parents—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter. In his mid-twenties, Calder moved to New York City, where he studied at the Art Students League and worked at the ‘National Police Gazette,’ illustrating sporting events and the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Shortly after his move to Paris in 1926, Calder created his ‘Cirque Calder’ (1926–31), a complex and unique body of art. It wasn’t long before his performances of the ‘Cirque’ captured the attention of the Parisian avant-garde.

In 1931, a significant turning point in Calder’s artistic career occurred when he created his first kinetic nonobjective sculpture and gave form to an entirely new type of art. Some of the earliest of these objects moved by motors and were dubbed ‘mobiles’ by Marcel Duchamp—in French, mobile refers to both ‘motion’ and ‘motive.’ Calder soon abandoned the mechanical aspects of these works and developed suspended mobiles that would undulate on their own with the air's currents. In response to Duchamp, Jean Arp named Calder's stationary objects ‘stabiles’ as a means of differentiating them.

Calder returned to live in the United States with his wife, Louisa, in 1933, purchasing a dilapidated farmhouse in the rural town of Roxbury, Connecticut. It was there that he made his first sculptures for the outdoors, installing large-scale standing mobiles among the rolling hills of his property. In 1943, James Johnson Sweeney and Duchamp organized a major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which catapulted Calder to the forefront of the New York art world and cemented his status as one of the premier American contemporary artists.

In 1953, Calder and Louisa moved back to France, ultimately settling in the small town of Saché in the Indre-et-Loire. Calder shifted his focus to large-scale commissioned works, which would dominate his practice in the last decades of his life. These included such works as ‘Spirale’ (1958) for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and ‘Flamingo’ (1973) for Chicago’s Federal Center Plaza. Calder died at the age of seventy-eight in 1976, a few weeks after his major retrospective, ‘Calder’s Universe,’ opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Larry Bell

Larry Bell is one of the most renowned and influential artists to emerge from the Los Angeles art scene of the 1960s. Known foremost for his refined surface treatment of glass and explorations of light, reflection and shadow through the material, Bell’s significant oeuvre extends from painting and works on paper to glass sculptures and furniture design. Bell’s understanding of the potential of glass and light allows him to expand visual and physical fields of perception, and his sculptures to surpass traditional bounds of the medium. He has said: ‘Although we tend to think of glass as a window, it is a solid liquid that has at once three distinctive qualities: it reflects light, it absorbs light, and it transmits light all at the same time.’

Bell’s use of commercial industrial processes in his studio, located in Venice, California since the 1960s and Taos, New Mexico since the 1970s, demonstrates his unparalleled skill and dedication in each step of his sculptures’ fabrication. Since 1969, his studio has managed its own high-vacuum coating system that allows him to deposit thin metal films onto his glass surfaces, harnessing a little known technique developed for aeronautics to create an unprecedented body of work.

Inquire about available works

‘Chromophilia’ is on view now through 9 March 2022 at Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse.

Related Content

Current Exhibitions

1 / 9