Essays

Sculpture Kills

An excerpt from a forthcoming book about art and death, form and function

By Jillian McManemin

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Umbrellas, Japan–USA, 1984–91. Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 1991. Courtesy Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

October 9, 1991: Morning sunlight falls over 1,340 large-scale cobalt-blue umbrellas arranged across twelve miles of muddy hills in the Ibaraki prefecture of Japan, an area seventy-five miles from Tokyo. That same morning, across the Pacific, the sun rises over California to greet 1,760 large-scale yellow umbrellas erected along an eighteen-mile stretch of the Tejon Pass north of Los Angeles, linking the southern part of the state to the Central Valley. The Umbrellas, Joint Project for Japan and U.S.A., the newest work by the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude has finally opened. “Blooming” is the word the artists use to describe the moment the umbrella sculptures, each standing nineteen feet tall and weighing more than 450 pounds, unfurl via a winch designed to be operated by a single person of average build—Jeanne-Claude has tested the mechanisms herself and jokes that if she can do it, anyone easily can. The process of opening a single umbrella takes around forty-five seconds. Opening all 3,100 that day takes 2,600 workers. It is crucial to the artists that the bloom happens in their presence, which involves precise timing both in Japan and California. In the leadup to the unfurling, the weather in Japan has turned; heavy rains pound the umbrellas on the Japanese hillsides. A diary of the project kept by Christo and Jeanne-Claude reads:

10.06.1991—Typhoon #21 is approaching Japan

10.08.1991—Waiting for the rain to stop, workers and monitors clean up along the roads in the project area in Ibaraki and California

The diary includes bullet-point notes on advancements and setbacks for the Umbrellas project, as well as brief notes about who’s coming on board to work. Sometimes there are notes about the artists’ travel and whom they have had dinner with. As I read the entries, I’m intrigued about the diary but unclear how it is kept. Is it an open book maintained by both members of the couple or the journaling habit of one, double-checked by the other, perhaps highly edited? I somehow think it’s mostly the work of Jeanne-Claude, though I have no basis to make such a claim. My friend Sonya says the diary should be considered through the same lens as reality TV; I believe she actually cited VH1’s Behind the Music.

To decide which company would manufacture the various parts of the umbrella sculptures, the project’s contractor organized a competition. Prototypes were taken to a field in Cheyenne, Wyoming, considered to be among the windiest places in the United States. In addition to field testing, four wind machines were also employed to gauge the wind forces that the sculptures could safely withstand, and the prototype eventually chosen, made by an American company, was further tested in the largest wind tunnel in the world, in Ottawa, Canada, pushing the sculptural form to its limits and determining it could endure wind speed up to 64.6 m.p.h. when open and 100 m.p.h. when closed.

In Japan at 5:50 a.m. on October 9, seventy-four teams of ten people open the blue umbrellas. Then Christo flies to California and, with the time difference, is present on the same morning for the same process halfway across the globe, arriving at LAX at 8 a.m. and watching the yellow umbrellas begin to unfurl until early afternoon.

10.09.1991—We see the Blooming of the Blue Umbrellas in Ibaraki that morning. Then Christo, Wolfi and Masa fly to California and see the Blooming of the Yellow Umbrellas on that same morning. Jeanne-Claude, Sylvie, Simone, Anna Marÿke, Harriet and Vladimir stay in Japan. Most of the subcontractors go home; the monitors remain.

After “blooming day,” the piece is retitled The Umbrellas, Japan–USA,1984–91. Crowds flock to both sites, strolling by, gazing up at the umbrellas, picnicking beneath them, taking photos. A wedding ceremony takes place under one in California. At certain points, both locations meet a highway. In California, the installation is viewed easily from a stretch of Interstate 5. In Japan, the umbrellas are spread around Route 349, alongside and even into the Sato River, installed in flowing water, placed to follow the natural patterns of the rice paddies and arranged closely to reflect the shadowy, wet mood of the valley. The umbrellas in California are placed farther apart across the mountains, their golden color echoing the dry blonde grasses, the sunshine and the cinematic, gleaming idea of the West that undergirds American identity. The two coastlines were chosen because of their geographic similarity as inland valleys. The artists saw the two vast umbrella-pocked spaces as a diptych, separate but completing each other.

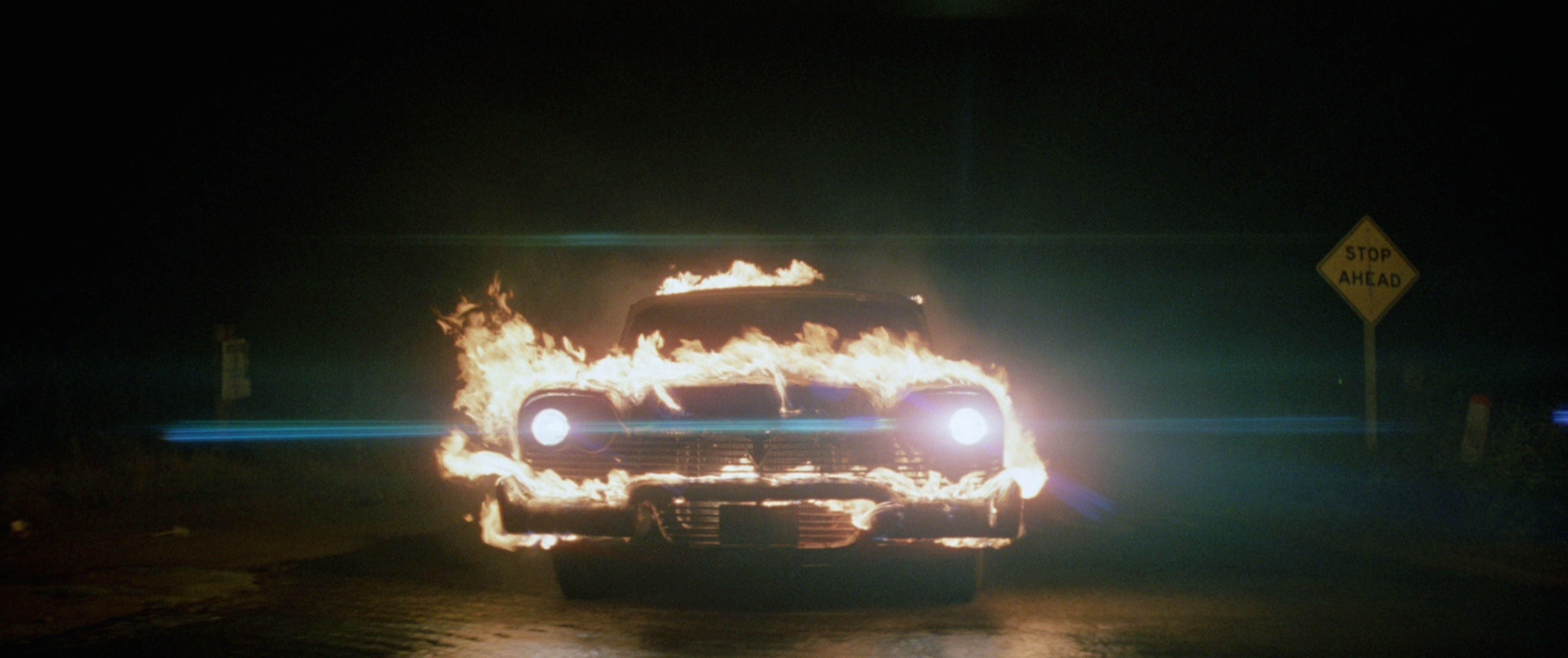

Film still from John Carpenter, Christine, 1983. TCD/Prod. DB/Alamy Stock Photo

By the end of October the installation is being visited heavily in both locations and has become a media phenomenon, especially in California, where the yellow umbrellas seem to be the perfect complement to the fall light. But then late on the afternoon of Saturday October 27, it suddenly all curdles, sours, comes undone. A shawl of fog flows into the valley, its purple tint illuminated by jagged lightning. Rain follows. The form of the sculptures slides slowly back into their function. Within a few minutes, a storm rips through the canyon, engulfing everything, consuming it. Evacuation orders are issued. Workers rush to close the umbrellas near the highway as the storm leaves half of Bakersfield without power.

Visitors run to safety as the entire installation becomes a sight of calamity. Dust kicks up and it’s hard to see more than a few feet in some places. Lori Keevil-Mathews, a thirty-two-year-old insurance agent from Camarillo, visiting the installation with her husband that afternoon, is walking along Digier Road, a winding trail not far from Interstate 5, and is trying to leave, shield her eyes from the kicked-up dust. I imagine dirt being in her mouth and her hair whipping around her face. Her husband is trying to pull her from the road. The gust rips three umbrellas completely apart. A fourth, a bit farther back, is uprooted and it, along with its heavy concrete base, flies across road, catching Keevil-Mathews and crushing her to death against a boulder.

The general contractor for the installation, Augie Huber, calls Christo and Jeanne-Claude with the news of the toppled umbrella and the death. Despite all the engineering planning and wind tests, Huber says, the elements were simply too powerful. “It was like a black wall, like nothing I had ever seen in my life,” he said. “It was moving so fast, it was unbelievable.”

The project, in both parts of the world, ends abruptly, on orders from Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Suddenly, the two sites are swarmed with crew members in a panic to deinstall. In the shadowy wet valley at the Japanese site, workers wade into water to remove umbrellas with cranes, uprooting them from their submerged steel bases. When the boom of one crane removing sculptures accidentally touches a 65,000-watt power cord hanging near the ground, the jolt fatally electrocutes a worker named Masaaki Nakamura. When the artists hear of this news, so soon after the tragedy in California, they immediately fly to Japan to be with the project’s other workers. This is the last journal entry published for the project:

10.31.1991 Accident during the removal in Japan. We fly to Japan.

Meant to last for three weeks the Umbrellas remained on view for eighteen days, and was viewed by an estimated three million people.

My journal reads:

01.12.2020 The start of the new year began with images of people fleeing to the ocean wearing respirators. The sea and sky were brick red, matte, and opaque, the world glowing from the inside out. The start of the new year began with Australia on fire. Billions of animals are dying. It feels like we are going to war. The adrenaline of my last bout of housing drama has left me. I moved into my new place on the 2nd. I’m finally settled all the way at the end of Greenpoint Ave. on a dead-end cul-de-sac in a nondescript building behind Greenpoint Storage Plus, next to the bridge on the Newtown Creek that connects Greenpoint to Long Island City. The creek is dark, silty and the sound of trucks rises from all directions. There are RVs on this block, a small sailboat someone lives on. I’m supposed to befriend him for boat rides in the summer, according to the other artists here. There’s a trucker parking lot right outside of my window. It’s an ecosystem, and I’m the new creature. It’s not legal to live here but it’s been occupied by artists for the last 15 years. I took over my friend Tin’s space, all the way in the back. Tin built the loft, which has all these little trap doors and secret spaces for storage and a closet that folds into itself. The idea was that you could completely live here but sort of conceal that you did at the same time, for studio visits and to create a clean workspace, both physically and psychologically. It’s painted all white, the floor, walls, and ceiling. I put a fresh coat of Rustoleum enamel on the floors and ended up with a headache. That was on New Year’s Eve. Then I went out all night. I remember when I was twenty-three with Tin, coming down off ecstasy after we had gone out dancing. I had glitter on my eyes. Tin had stretched plastic all over the loft and kept a space heater by his bed. It felt like a terrarium. It wasn’t entirely safe. I wonder if it’s safe here now. I’m always worried about fires, especially after the one at the last place where I lived, in Bushwick.

The making of abstract sculptural shapes whose function was to heighten the efficiency of killing, battle, hunting, defense predates the making of sculptural reproductions of the body. Abstract sculpture is, in a sense, a return to an origin story. We imbued abstract objects with our murderous intentions, animating them for violence.

In 1951, David Smith made a sculpture titled Australia, which I learned about while working for his estate in 2019. Smith photographed the piece in the fields of Bolton Landing in upstate New York with the camera titled up so that the sculpture took up a broad expanse of the winter sky. Sculpture as far as the eye could see. Sculpture over the hills and valleys. Sculpture perched at the edge of a cliff. Australia stands in a playful gesture of alarm, reaching out so far from its base with prongs and curves of metal. It looks as if it should teeter over.

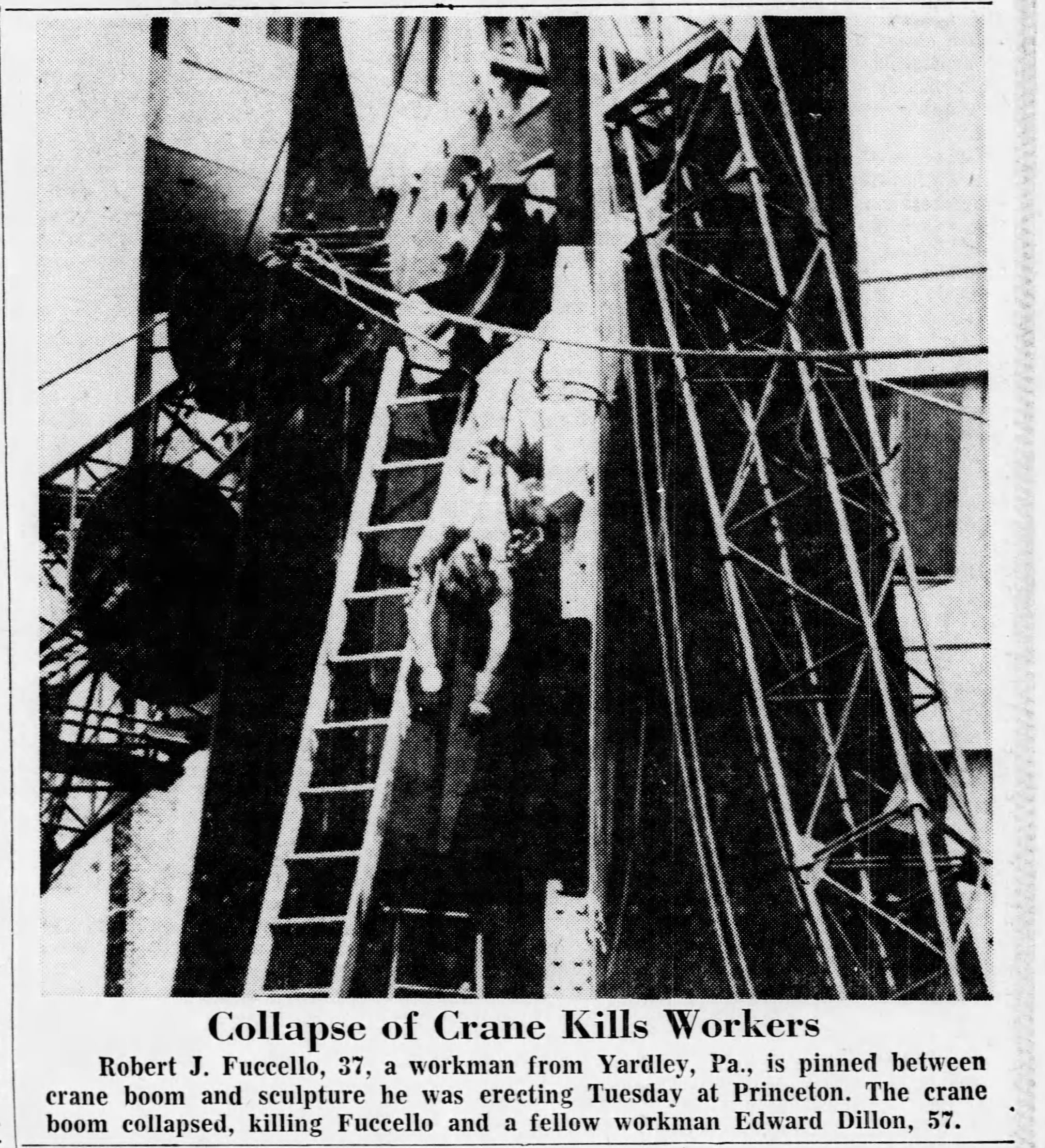

The Umbrellas, Japan–USA,1984–91 was the first instance I’d ever read about in which a sculpture causes the death of a person. The image of a flying deadly umbrella flashed in my mind over a number of years, daring me to looked at art differently, inserting calamity into the realm of the possible, positing an extreme and omnipresent potential for contradiction, a space in which art acts in defiance of expectation and of its creator’s intentions. The idea of writing a book about sculpture and human fatality gradually became an obsession, and I began to collect stories of other such instances: the installation of a Calder sculpture in Princeton, N.J., in 1970 in which a crane accident killed two workers, Robert J. Fuccello and Edwin Dillon; Richard Serra’s Sculpture No. 3, two five-ton steel plates balanced against each other, which killed a rigger named Raymond Johnson at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 1971 when one of the plates fell on him; Luis Jiménez’s Blue Mustang, a towering equestrian sculpture, a portion of which fell on Jiménez in his studio in 2006 and fatally severed an artery in his leg.

One winter day in 2020, I skipped going into the Smith estate office and worked instead in the Art and Architecture Room at the New York Public Library, digging up an essay titled “Sculpture and the Weapon,” written by an artist named John Stephan. Originally published in the art journal Tiger’s Eye in 1948, it came to my attention through a discussion in Robert Slifkin’s 2019 book The New Monuments and the End of Man. In one page, Stephan’s essay attempts to reorient the history of abstract sculpture, drawing a line between it and humankind’s development of weapons. When we began to make objects to use as weapons, we placed an intermediary between us and our opponents, lending to killing a more premeditated, calculated aspect, a skill, even an art. The making of abstract sculptural shapes whose function was to heighten the efficiency of killing, battle, hunting, defense predates the making of sculptural reproductions of the body. Abstract sculpture is, in a sense, a return to an origin story. We imbued abstract objects with our murderous intentions, animating them for violence. The book I envisioned would delve not just into the history of abstract sculpture but into the history of how we make and use objects in general, the ways in which the history of tools is blood-soaked, the idea that sculpture was born splashing around in it. Incidents like the Christo and Jeanne-Claude accidents assume mythic proportions in part because of our ideas about sculpture in general. If it has a function, that function is to remain still, to stay forever in a position to be looked at, to accept the gaze. I started fantasizing about sculptural sentience. Maybe a sculpture didn’t want to be viewed. Maybe it minded being left in the scorching sun, on display and opened like a flower. Did the umbrella know it was only temporary? That people could view it for only three weeks and that its life was uncertain after? That it would live only in reproduction? A bridge collapse, an architectural accident, a failure of urban design, a car crash—none of these create the implications and feelings of art accidents. Such incidents, strewn across the 20th and 21st centuries, fracture and reorient what a sculpture is meant to be and what a sculpture is. They exist as a sinister wink in the direction of all the movements and theory that sought to bring sculpture and material closer together.

Clipping from The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 3, 1970 © 2023 Newspapers.com

Luis Jiménez, Blue Mustang, 2008. Photo: Jillian McManemin

My journal reads:

02.15.2020 It’s the four-year anniversary of the fire. I called Robert, for two reasons: He has the type of memory that makes him able to recall events and even things I’ve said at 2 a.m. at parties with an accuracy that is both useful and unnerving, and the second was that I wasn’t home when the fire started. He was, and he was the one who saw it happen. I was in the East Village. I left early that morning to take care of Steve Cannon, a poet, jazz musician, curator, and founder of A Gathering of The Tribes—a nonprofit art and literary magazine. Steve called himself “The Blind Guy.” His assistant was out of town. I was going to fill in, and I had to be there around 9 a.m. with coffee and The New York Times, so I could read it to him. I’d hang out for the day and send emails that he’d dictate to me, make sure he was all set with food and keep him company. Because Steve was blind, and because I enjoyed his company so much, as soon as I arrived at his apartment, I shut my phone off and put it in my bag. Steve chain smoked as I read the news. I didn’t smoke because I never smoke in the morning. Antonin Scalia died, and politicians were scrambling to replace his seat in the Supreme Court. I also told Steve self-effacing stories about the semi-famous painter I used to work for, who I slept with. Steve was laughing, sprinkling ash all over himself and the couch.

Robert told me he heard a “crackling” that morning, very loud, loud enough to wake him from a boozy slumber. He rushed from his room to find a small fire by my bedroom door, then he ran to the kitchen in a panic to get a pot of water. By the time he got back, the wall was fully ablaze. He thought I was asleep in my room, so he ran in, past the flames, through black smoke, frantically pawing my mattress to find me. When I went to a Chinese take-out place on Avenue D to get Steve something to eat, I turned my phone back on to an explosion of missed calls, voicemails and texts telling me that my loft was on fire. After I received the news, I still went to get Steve his lunch and then to get him cigarettes. As I walked, my mind shuffled through all the objects in my life that I was attached to. I texted Robert: How bad is it? He told me to get back immediately and that it was not good, but that no one was hurt. Even Ruin, my little black cat of almost a decade, was fine.

The firemen pulled down the bookshelf in my room and ripped the wall open to reveal a metal door that I never knew was there. They busted out all the windows and the skylights. They sprayed water everywhere and since it was so cold many of the clothes in my closet were frozen with icicles. I lost only the really unwieldly pieces of art: a six-foot-wide video still of me jerking off on the floor in American flag panties that my girlfriend took when I was twenty-two. I was in her kitchen, flanked by cakes, writhing around in a gesture vaguely queer and political.

Even though no one was injured in the fire, it really scared me. I remember the smell. I can smell it now if I concentrate. Some of the books I have still smell faintly of it, their pages tinted darker. I thought the fire was the culmination of my precarious life and a terrible warning that I could have died or could have been killed not just in a fire but in myriad other ways. When I had first moved into the loft, I’d made a photocopied black-and-white zine called HOUSE ON FIRE, which featured stills from all the films I could think of that had scenes of houses on fire, like Firestarter and Gone with the Wind. We had open studios and an enormous party. I still have some of those zines, and shortly after the fire I remembered that little project and was hit with a sick feeling, as if I’d known what was coming as soon as I arrived.

–

Jillian McManemin is a writer and artist. Her work has appeared in BOMB, Hyperallergic and Texte Zur Kunst, among other publications and platforms. In 2020, she founded the Toppled Monuments Archive. McManemin presented work as part of the 2022 Whitney Biennial and has contributed work to the Anthology Film Archives, The Poetry Project and other international venues.