Essays

Lozano’s Labor

by Jo Applin

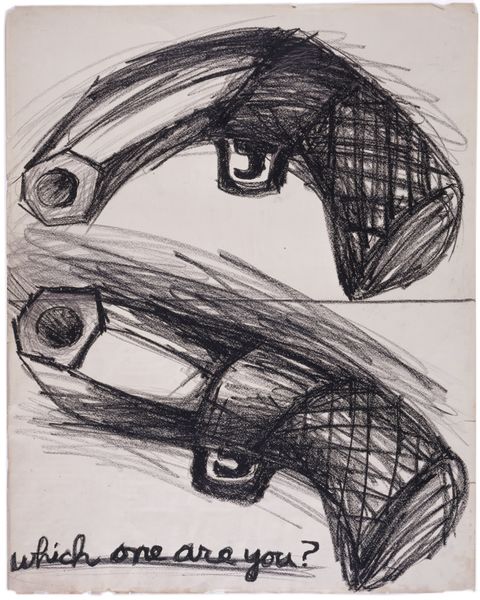

Lee Lozano, No title, c. 1962 © The Estate of Lee Lozano

- 5 July 2019

- First published in 2010 in conjunction with the exhibition “Lee Lozano” at Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Reproduced courtesy The Estate of Lee Lozano and Hatje Cantz.

- Related Artist

- Lee Lozano

Lee Lozano’s paintings from the 1960s are admired for their energy, daring physicality and tirelessness in investigating the body and issues of gender. Lauded by Lucy Lippard in 1995 as the foremost female conceptual artist of her time, Lozano disengaged herself from the New York art world completely by the early 1970s. Below is an excerpt from Jo Applin’s essay ‘Lozano’s Labor’, which captures the somatic, gestural brilliance of the artist’s early figurative vocabulary. Applin makes a case for Lozano’s place in the art historical canon as a pioneering conceptual artist whose work industriously interrogates the art/life binary. Although Lozano’s oeuvre is often divided among formal lines—drawing and painting, performance and ‘language pieces’—Applin charts how these intersect and form a continuous investigation into labor.

In 1961, using pencil, wax crayon, pastel, and paint, New York-based artist Lee Lozano began work on a series of cartoonish, violent, and erotically charged drawings that she would continue to produce for the next several years. These works—some hastily drawn on the torn-out pages of a sketchbook, others on canvases over two meters long—comprise roughly rendered industrial, artistic, and domestic items such as hammers, saws, pencils, light bulbs, wrenches, and plug sockets. At times, these semi-abstract tool drawings incorporate words and phrases, from the puerile and sexually explicit ‘he gave her a good screwing he said’ reads the title emblazoned across the top of one drawing of a block of wood. being sawn in half) to the elliptical, witty, and descriptive (‘a boring drawing’ is the inscription on a cross-section of the inner workings of an electric drill).

At other times, the human body unmistakably appears in the form of so many parts and orifices, penises and breasts, whether seamlessly morphing with the metal tools or being variously penetrated or ‘plugged’ by them. Lozano exploits the play of back and forth between body and machine, eroticism and aggression, to striking effect; the vagina as passive receptacle is a motif used by the artist as much as the more familiar formulation of the toothy and aggressive vagina dentata. In yet other instances, she renders gaping, red-lipped mouths filled by enormous anuses and protruding penises. She offers in these works a grotesque collection of body parts that variously seep, slide, and crash into one another as an endless chain of substitutions, switches, and elisions. At Lozano’s anarchic, idiosyncratic hand, parts of the body are retooled and tools are made bodily.

They appear bent, broken, and fused into a mechanical mismatch of sharp points, thickset handles, nail heads, clamps, and screws. In one mechanomorphic drawing from 1962, Crayola crayons slump and tilt as though so many tired, wilting bodies. Each one bears the distinctive logo, but she substitutes the color label on each wax stick ‘Cadet Blue,’ ‘Burnt Sienna,’ ‘Aquamarine’) with the words ‘Paint,’ ‘Cock,’ ‘Shit,’ ‘Light,’ ‘Tit,’ and ‘Fire.’ Continuing the perverse rearrangement of this most infantile of art materials, the point of each crayon is recommissioned to accommodate variously the tip of a penis, a nipple, a match, a flashlight, a paint tube, and a stubby turd. An attitude of precariousness permeates Lozano’s tool drawings such as this one, in which distinctions between subject and object, animate and inanimate, male and female no longer make much sense.

“In Lozano’s tool drawings, objects mate and morph, multiply and engage.”

In an undated pencil drawing from the early sixties, Lozano depicted an adjustable spanner gripping the head of a mallet—a caress of sorts, or maybe a bite. Another series of tool drawings and paintings render close-up angles of an adjustable wrench; at times it is barely recognizable, save as an ominous section of metal machinery, while in other instances its function and clamping action is clearly denoted. If the imagery of her peers, such as Lee Bontecou and Eva Hesse, has often been discussed as resolutely abstract, even unconscious representations of sexuality and the body as mechanized part-object, then Lozano’s drawings function as their desublimatory inverse. Eyes, mouths, vaginas, and penises cascade across the page and positively drip with an overt and perverse sexuality—from the crayon sketch of a naked man’s body, his buttcheeks fastened together with industrial-size staples, to her series of body box drawings of squashed cardboard boxes containing body parts that poke out from the middle—a cock here, an eye there.

Lee Lozano, No title, ca. 1962 © The Estate of Lee Lozano

Lee Lozano, No title, 1964 © The Estate of Lee Lozano

For all her idiosyncrasies, however, situating Lozano and recognizing her relationship to her contemporary milieu is now a crucial and timely project. That she has slipped somewhat from view since her decision in 1969 to ‘drop out’ of the art world, at the same time very publicly declaring her rejection of ‘women,’ has only fuelled attempts to understand the artist as a kind of renegade.[1] I want to argue against readings that situate Lozano as an outsider and to suggest that, on the contrary, she was absolutely keyed into a contemporary rethinking of the body, gender, and a politics of Eros, each of which runs through her early work—some years, in fact, before such concerns had entered the political or aesthetic horizon of her contemporaries. Constantly questioning and pushing notions not just of art but subjectivity, of how one forges a subject position for oneself through a blurring of art and life, of art as life, traverse Lozano’s eclectic career.

“The idea of work—as strategy, as art, as a way of living—saturates her thinking, from her early drawings right through to her later performance projects such as Dialogue Piece…”

The idea of work—as strategy, as art, as a way of living—saturates her thinking, from her early drawings right through to her later performance projects such as Dialogue Piece (in which she documented encounters with other artists and friends) and Grass Piece (in which the artist charted her activities and thoughts during a period of time spent smoking marijuana). While Lozano’s vivid sexual language marks her difference from the abstract eroticism of her immediate peers, her use of expressive gesture and fast, loose lines connects her to earlier modes of abstract painterliness that had dominated the New York art world since the forties.[2] It makes less sense, though, to relate her line to the abstraction of Jackson Pollock, say, or Willem de Kooning. Instead, her visual vocabulary shares more with the Monster Roster, a group of artists who were working out of Chicago in the late fifties and early sixties.

This loosely affiliated group of artists included Nancy Spero, H. C. Westermann, Leon Golub, and Philip Guston. Their work was marked by a postwar language of warfare and brute aggression, often overlaid with a sexualized mode of figuration. The work of the Monster Roster artists would have been familiar to Lozano, as she had studied art at the Art Institute of Chicago in the late fifties. Her tool drawings in particular connect in striking ways with Spero’s scratchy, sexually charged imagery. Like Lozano, Spero too was an artist investigating the limits and formal possibilities of text and image, Eros, and violence in her own working-through of her position as a woman artist.[3] Lozano’s tool drawings range in appearance from carefully rendered figurative forms to thick, scrawled, expressive sketches of anthropomorphi tools that coagulate into a riotous mess of eroticism, violence, and black humor.

At first, a garish sprawl of dense, waxy colors, and later muted blacks and grays, the insistence upon the tool as motif and maker of the imagery—that her drawings of crayons are made in crayon, for example—is a literalism she wittily exploits. The artist depicts the tools of her trade alongside a panoply of other tools that one encounters not only in the artists’ studio, but also those more likely to be found at an industrial work site or in a toolbox. In 1964, Lozano’s tool drawings took a different direction, and the once loose, sketchy aggression of the thick pencil and crayon lines was replaced with close-up angles of pointed drill bits and hammerheads. These wax-stick works are larger than the earlier colorful drawings and operate according to a different logic that is at once monumental, austere, and terrifying. While overt sexual and scatological references no longer appear, this does not represent a straightforward shift towards a Minimalist aesthetic.

Lee Lozano, No title, ca. 1962 © The Estate of Lee Lozano

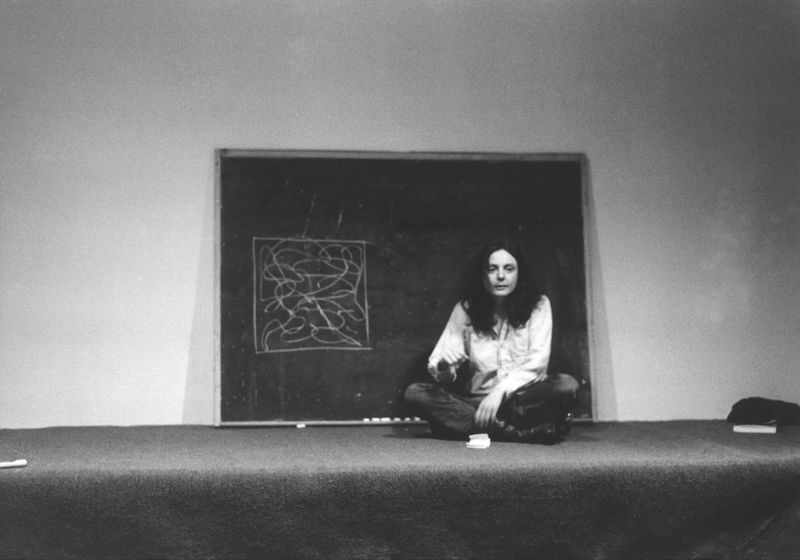

Lee Lozano lecturing at NSCAD, Halifax, July 16, 1971 © The Estate of Lee Lozano

The tools, far less recognizable now as utilitarian objects, are figured variously as malleably soft and unremittingly hard. In these works, the tools, screws, and drill bits are held in tension, barely touching and suspended in a moment prior to the aggressive act of smashing, hammering, screwing, and drilling. In addition to these pencil and crayon works, Lozano made a series of multi-paneled paintings of tools comprising similarly extreme close-ups of drill bits and screwdriver heads painted in shades of slick granite black, and gun-metal gray. These are painted in stark monochrome shades with a three-inch house painter’s brush, which creates thick, even fields of color articulating sharp points, sheer angles, and hard-edged spiraling forms in careful, laboriously finessed lines—the thread of a screw, the flat end of a hammer.

Tools here function as bodily correlates as much as they do cold, industrial machinery, as if to reveal the uncanny flipside to the industrialized and rational sphere of mechanized labor. The relationship these drawings and paintings have to their ostensible subject matter is perverse and rooted in a deeply charged eroticism and aggression. In Lozano’s tool drawings, objects mate and morph, multiply and engage. Cropped close-ups at times make it hard to discern what the tool being depicted is, while at other times the line between body and tool, subject and object, is obscured and made strange. In some drawings from this period, the body figures explicitly, but only as the object of violent acts—a vagina as electrical plug socket, or a pair of denim jeans with a large spanner shoved into the zipper in a humorous acknowledgement of the machismo then associated with the artist’s workshop.

Such a deflationary impulse is again seen at work in a colorful rendering from 1962 of a typewriter. Each key, like the Crayola crayons, has been retooled, with the letters of the alphabet replaced with dollar signs, grinning mouths, and a list of words that spill into one another, including ‘shit,’ ‘sleep,’ ‘no,’ ‘stop,’ ‘cunts,’ ‘cocks,’ ‘balls,’ ‘smoke,’ ‘think’ and ‘work.’ Instead of a sheet of paper, a long, flat, flesh-colored penis has been fed through the typewriter, mangled and pressed into a thin sheet onto which, when the keys are hit, the words, demands, insults, instructions, and desires will be imprinted.

–

Jo Applin is author of Lee Lozano: Not Working and Eccentric Objects: Rethinking Sculpture. She teaches modern and contemporary art at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London.

Lee Lozano’s early paintings are included in the group exhibition “Material Actions,” on view at Hauser & Wirth St. Moritz from 7 July – 8 September 2019.

1. There is no room here to expand upon ‘drop out’ pieces such as General Strike Piece and her rejection of women. For two fine essays addressing this, see Helen ‘Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out: The Rejection of Lee Lozano,’ Art Journal (Winter 2002), pp. 64–70; and Johanna Burton, ‘The New Honesty: The Life-Work and Work-Life of Lee Lozano,’ in Helen Molesworth, ed., Solitaire: Lee Lozano, Sylvia Plimack Mangold, Joan Semmel (New Haven, 2008).2. ‘Abstract-eroticism’ was a phrase coined by Lucy Lippard in the mid-sixties to describe emerging forms of representation that were both resolutely abstract yet unmistakably erotic in their undertones. See her two important essays, ‘Eccentric Abstraction,’ Art International 10, no. 9 (November 20, 1966) pp. 28, 34–40, and ‘Eros Presumptive,’ 1967, reprinted in Gregory Battcock, Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1995).3. See Mignon ‘Spero’s Curses,’ October 122 (Fall 2007), pp. 3–30.