An artist of powerful originality and singular vision, the German-born Swiss artist Meret Oppenheim (1913 – 1985) remains one of the most dynamic figures of 20th-century art. Despite being affiliated with some of the most influential art movements of the 20th Century, including Surrealism and Dada, Oppenheim defied categorization. Her wide-ranging, boundary-breaking practice will be showcased this June in an exhibition spanning painting, drawing, sculpture and design.

Portrait of Meret Oppenheim © Keystone / Peter Studer / Walter Studer

Born in Berlin, Oppenheim moved to Southern Germany and Switzerland as a child, living in various places including Delémont and Basel. In 1932, at the age of 18, she travelled to Paris to become an artist. Marking this turning point in her career is a rarely exhibited, early watercolor painted on the writing paper of Hotel Odessa in Montparnasse from the same year.

Soon after, Oppenheim found herself part of a circle that included Alberto Giacometti, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, André Breton and Max Ernst, among many others. Though often eclipsed by the international success of ‘Object’ (or ‘Déjeuner en fourrure’), 1936)—the fur-covered cup, saucer and spoon that remains her most well-known work—Oppenheim’s artistic output already included drawings, oil paintings, collages and assemblages during this time.

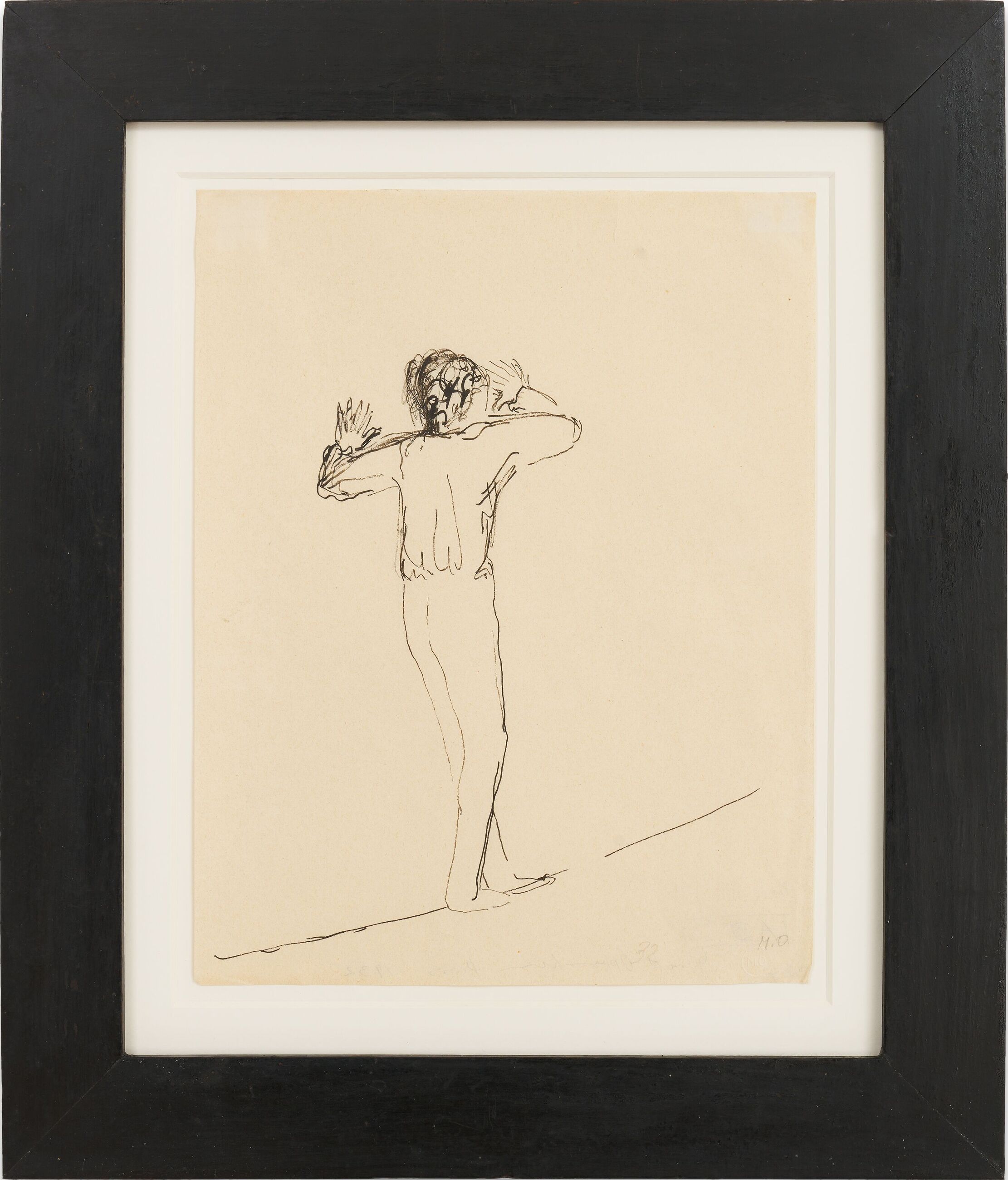

Oppenheim returned to Switzerland in 1937, escaping her early fame in Paris following the sensation of ‘Object’. Living in Basel, she enrolled at the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule to study restoration, conservation and painting. Her oil paintings and drawings from this time show a new focus on personal, often melancholic subject matter, reflecting upon the dark years of the 1930s and the outbreak of World War II.

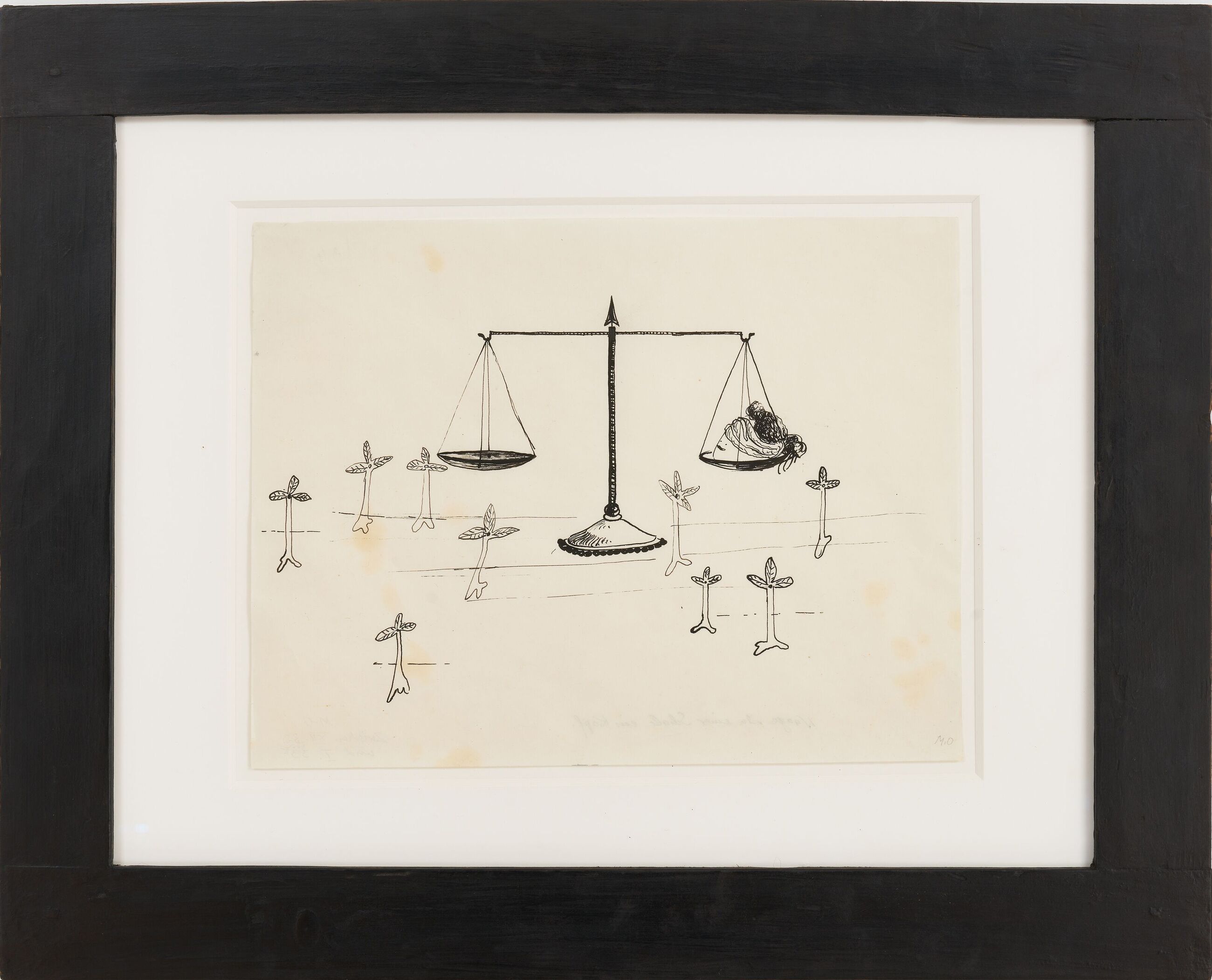

Meret Oppenheim

Waage. In einer Schale ein Kopf (Scales. A Head in One Tray)

December 1932 - January 1933

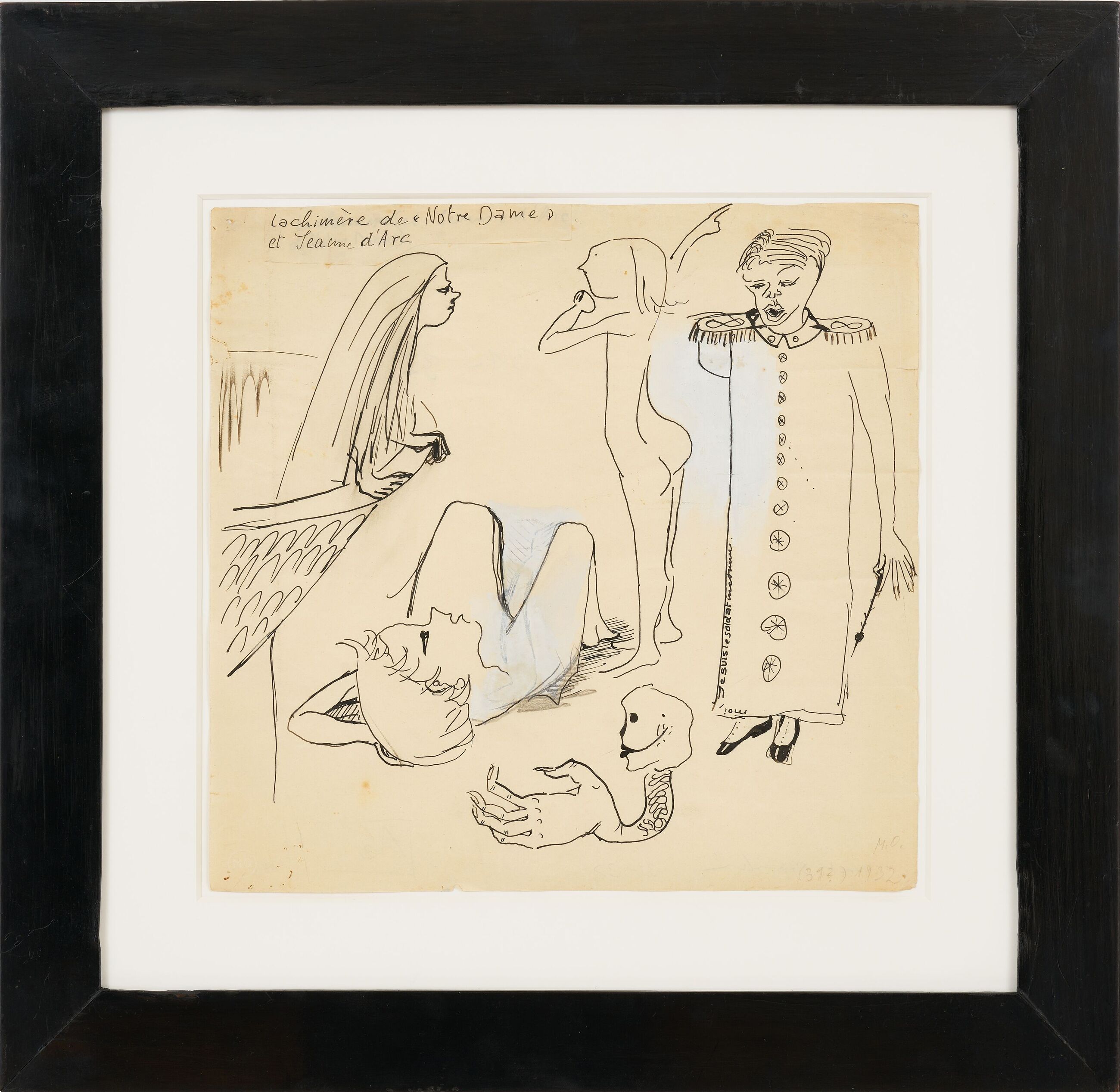

Oppenheim increasingly employed a figurative visual language that incorporated motifs from fantasy and myth, seen here in works such as ‘Die Erlkönigin’ (1940) and the extraordinary ‘Daphne und Apoll’ (1943). A highlight of the exhibition, ‘Daphne und Apoll’ exemplifies Oppenheim’s talent for bold artistic reinterpretation through its depiction of the metamorphosis in the myth of Daphne and Apollo—a moment of transformation that Oppenheim further exemplifies as she subjects not only Daphne but also Apollo to change.

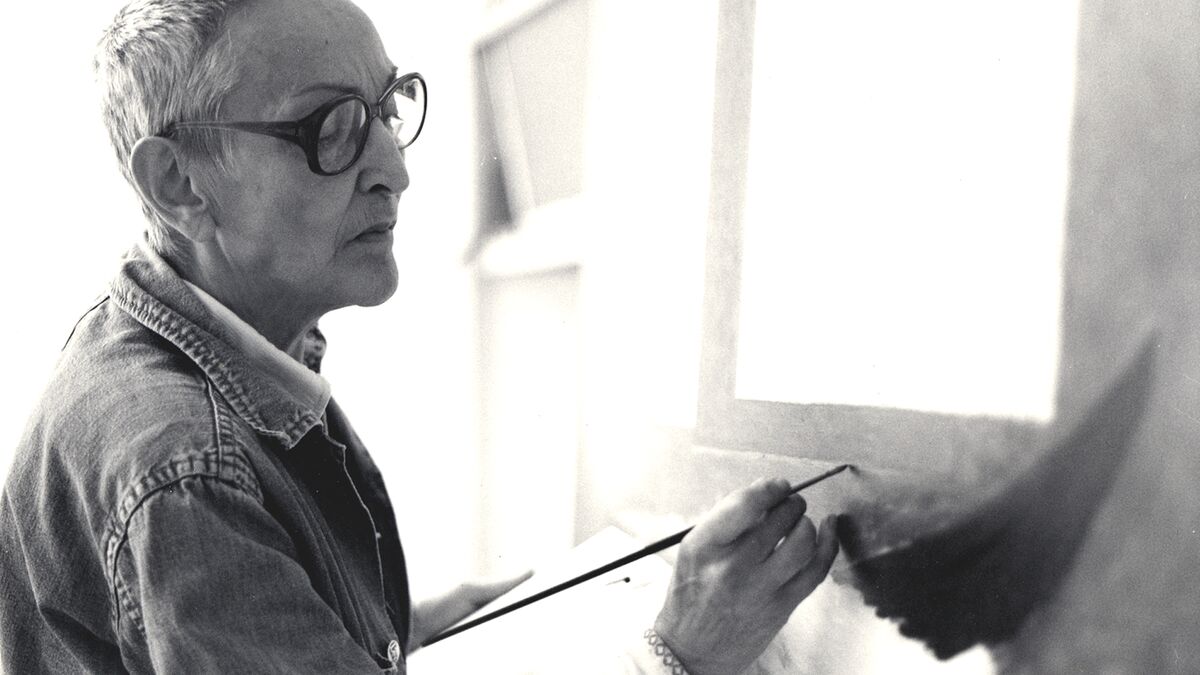

Meret Oppenheim while working on ‘For Caroline von Günderode’, March 1983, in Paris. Photo by Nanda Lanfranco, Genoa, Italy.

Following a period of crisis that saw her produce comparatively little, but often highly personal work, Oppenheim returned to art making with fervour in 1954. Works on view from this period include ‘Genoveva über dem Wasser schwebend (Genevieve Floating Over the Water)’ (1957), one of many works in which Oppenheim explored ideas around social convention and identity through the medieval legend of Genoveva, a young noblewoman banished after being wrongly accused of adultery by her husband.

Other paintings such as the rarely exhibited ‘Le sang de l’astre’ (1956) reflect Oppenheim’s increasing engagement with abstraction, avoiding repetition or any specific style. ‘Idee für Maske’ (1959), meanwhile, recalls Oppenheim’s use of mask construction as a vehicle for the transformation both of found materials and of the wearer’s own identity, including gender, via such disguises.

‘I simply always did what I felt like doing, anything else wouldn’t agree with the way I work, committing to a particular style would’ve bored me to death.’—Meret Oppenheim

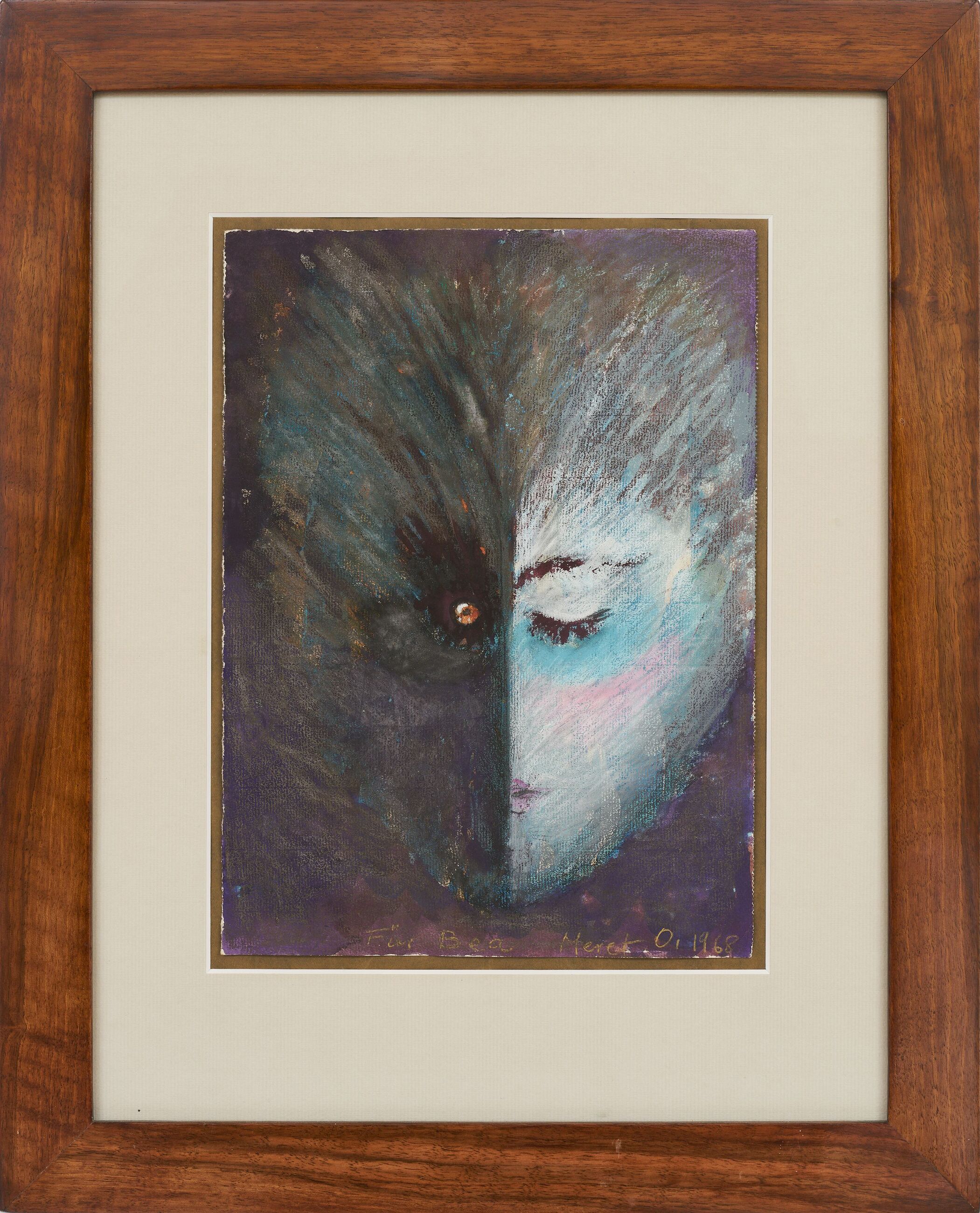

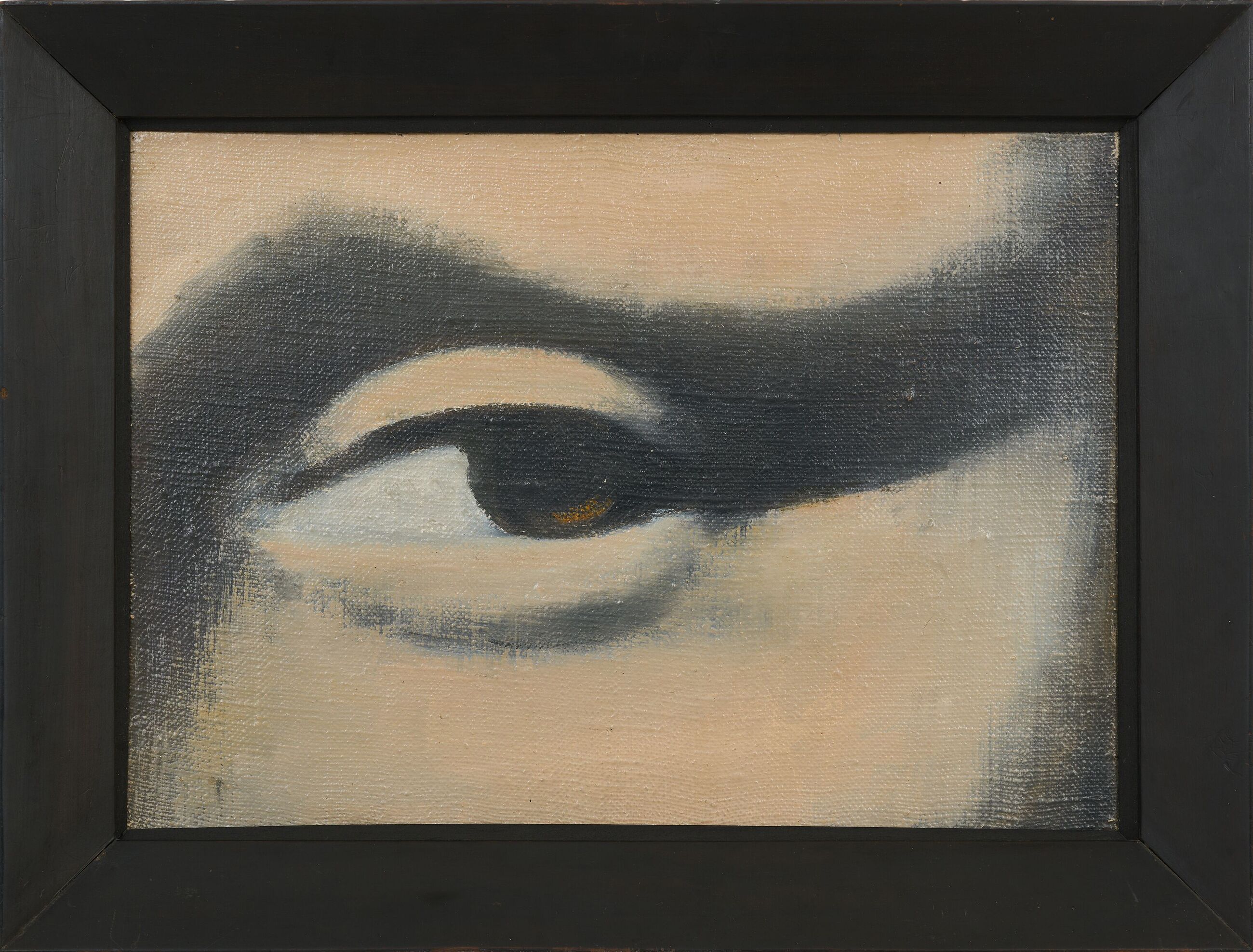

Like Marcel Duchamp, one of her closest friends from her early years in Paris, Oppenheim dealt with Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic image of the Mona Lisa in her work. In her small painting ‘Das Auge der Mona Lisa’ (1967), she focuses on the left eye of Leonardo’s mysterious and yet still unknown woman, creating a work of disturbingly intense presence, in which the interaction between the painted eye and the observer becomes as enigmatic as Leonardo’s iconic work.

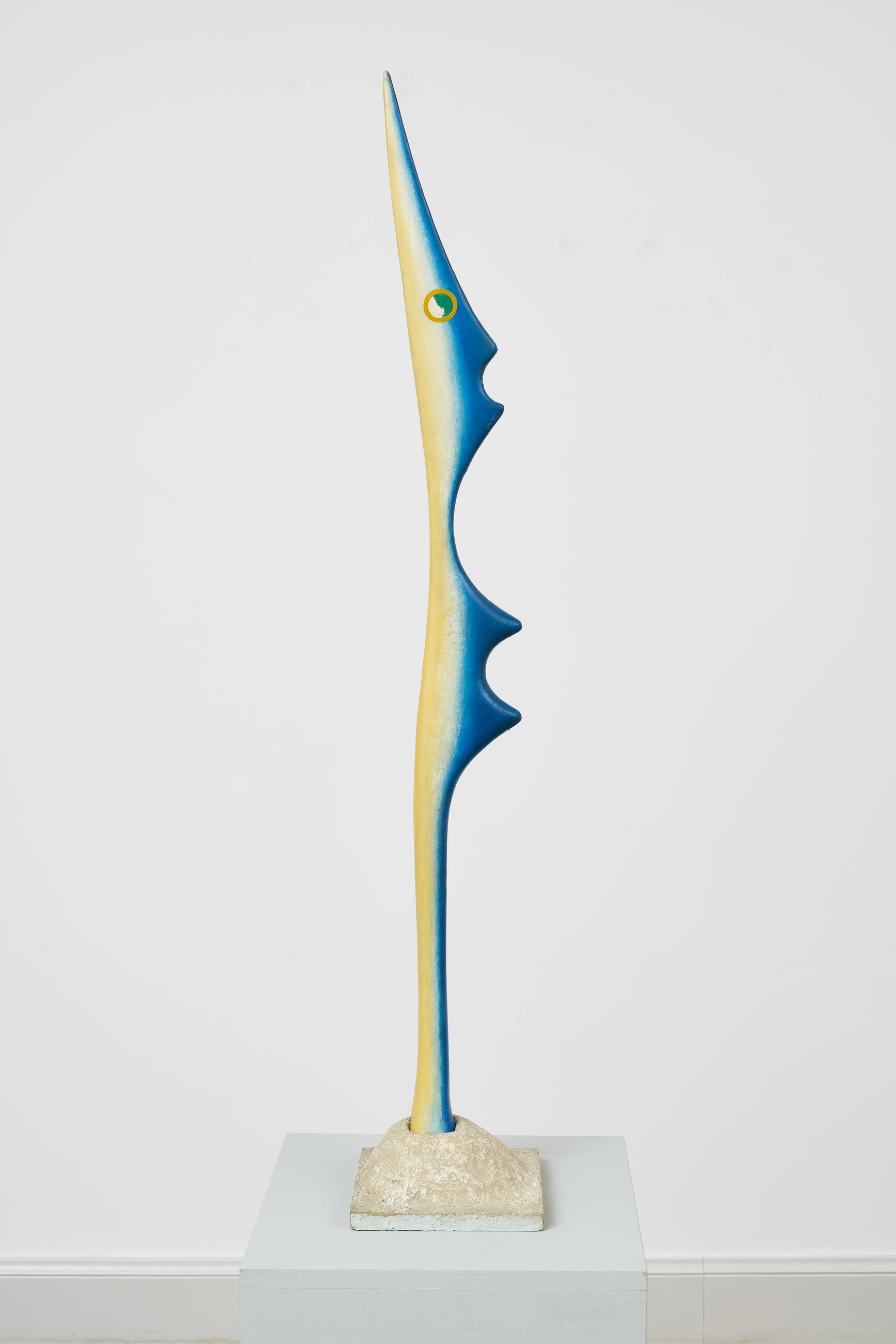

‘La dame bleue’ (1963), however, is a fine example of Oppenheim’s sculptural oeuvre in the 1960s. Its elegant, vertical and sparsely colored form evokes a female figure, and its flower-like, organic abstraction conveys yet another aspect of the artist’s stylistic variety.

Though too often associated with Surrealism, Oppenheim objected to being claimed by any one movement or style.

Meret Oppenheim with the model of the Berne Fountain, ca. 1982 / 1983.

Rather than tracing the evolution of Oppenheim’s multifaceted artistic practice, the exhibition celebrates its varied and singular nature. Recalling her iconic ‘Object (Le déjeuner en fourrure)’—by this time created more than 25 years previously—the playful ‘Eichhörnchen (Squirrel)’ (1970) transforms the handle of a beer stein into a fluffy squirrel tail, engaging with notions of masculinity, eroticism and the macabre while also displaying the artist’s trademark wit.

In 1984, just a year before the artist’s death at the age of 72, Oppenheim’s work was celebrated with a major retrospective at Kunsthalle Bern that was based on one of her final projects, in which Oppenheim constructed an imagined exhibition of her life’s work through more than 200 drawings of her own works in miniature. Almost four decades later, the same project would also serve as the inspiration for the retrospective ‘Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition,’ which travelled from Kunstmuseum Bern (2021 – 2022) to the Menil Collection, Houston TX (2022) and The Museum of Modern Art, New York NY (2022 – 2023).

Related Content

Current Exhibitions

1 / 10